Image: John McMillan/Trout Unlimited.

Standing on a cobble beach where the river meets the sea, I stare across the glassy swells, listen to the gentle lap of waves on shore, and inhale the scent of salt and seaweed. An oily disturbance at the surface gives me a target, and I cast.

It was 2016, and approximately 2,000 adult pink salmon had returned to the Keogh River in Port Hardy, Vancouver Island, BC. Fly-fishing for pink salmon at the river mouth was fun and we caught fish. But in 2014, over 800,000 adult pink salmon returned to the river… more than 400 times the number of fish I witnessed two years later!

Wild variations in salmon returns like this are not uncommon, driven by changing ocean conditions, fisheries, and other factors. But it raises the question – how does the number of spawning salmon affect other river fishes like steelhead?

In this week’s Science Friday post, we discuss a new paper by myself and my supervisor (Dr. Jonathan Moore), scientists at Simon Fraser University in BC, Canada, where we show how high numbers of salmon may be more important than we previously thought for river fishes such as steelhead.

Young steelhead may live and grow for several years in coastal rivers prior to heading to the ocean, and are a part of stream food webs, along with other fishes like juvenile coho salmon and cutthroat trout, as well as less-appreciated fishes like sculpin. Stream fishes such as these love to eat eggs from spawning salmon. Eggs are easy to see, they don’t try to escape, and are much more nutritious and energy-dense than other prey food sources like aquatic insects.

Past research has shown that salmon eggs can provide enormous growing opportunities for stream fishes. But how many eggs are enough? How are these eggs divvied up amongst the different sizes and species of fish?

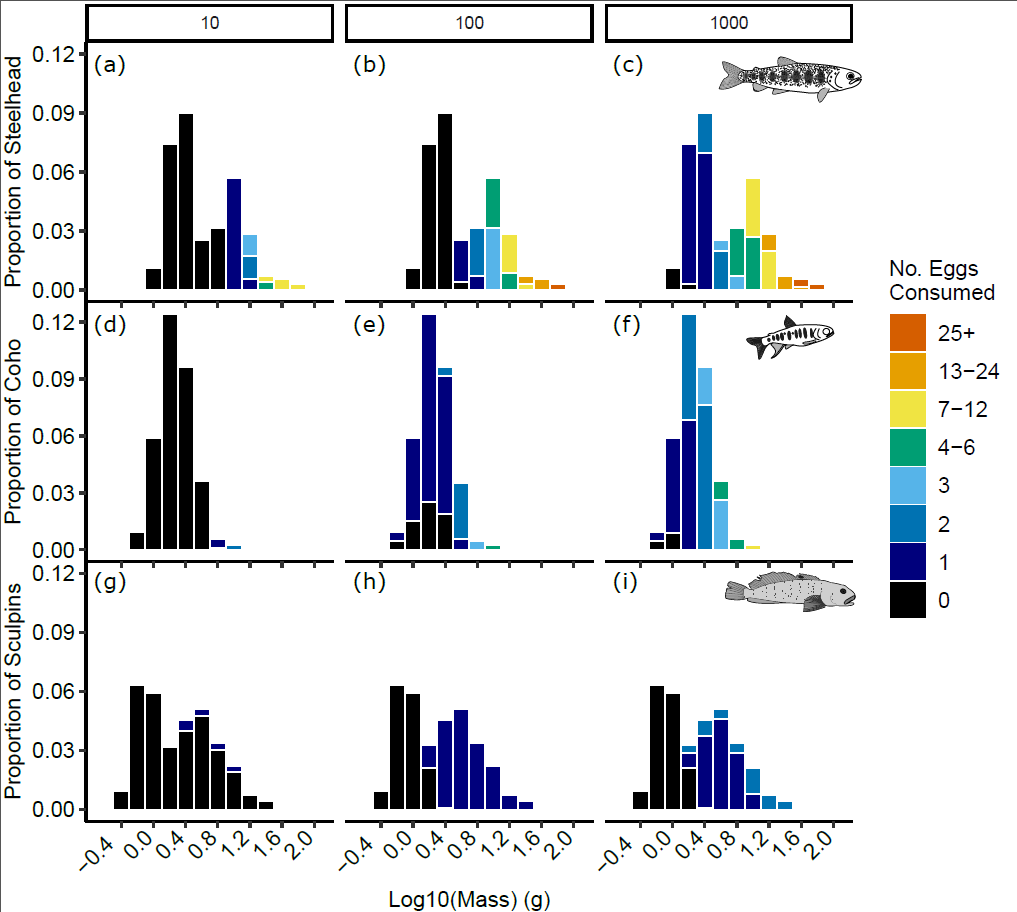

To answer these questions, we added different (but realistic) amounts of pink salmon eggs (ranging from 6 to 3,575 eggs) to different stream reaches in the Keogh River. After adding eggs and waiting for half an hour, we captured all the fish in each reach, and gently flushed their stomachs to see how many eggs each fish had eaten.

We discovered that as we increased the number of eggs added, not only did individual fish eat more eggs, but a greater diversity of sizes and species ate eggs. In other words, more eggs mean more sizes and species of fish can benefit.

In contrast, during times with low salmon abundance (and low numbers of eggs in the river), the largest and most competitive species of fish dominate over smaller and less competitive species and monopolize consumption of the salmon eggs.

In a parallel study in which we analyzed video of these fish feeding on salmon eggs as we increased the number of eggs added, the number of aggressive interactions between trout and salmon decreased. Basically, they became “fat and happy,” calling a temporary truce with neighbours to whom they were typically aggressive.

In general, smaller fish (particularly sculpins) were less likely to eat eggs than larger fish, with small fish needing more eggs before they could join the feast. Gram for gram, coho were the most competitive species. Young steelhead generally ate more eggs than coho, but only because there were lots of young steelhead that were larger than most of the coho.

So why does it matter if small fish get to eat salmon eggs? Research I led previously showed that the number of spawning pink salmon can be linked to steelhead migrating to sea at younger smolt ages (Bailey et al. 2018). In fact, while steelhead smolt numbers are still limited by density dependence (the habitat can only support so many fish), higher numbers of spawning pink salmon actually increase the number of smolts produced per female spawner.

Similarly, there is evidence that more pink salmon spawners can increase the numbers of juvenile coho (Michael 1995). Thus, there is some evidence that high abundances of spawning salmon can benefit stream fishes such as juvenile coho or steelhead.

What about the relationship between salmon spawners and the number of unburied salmon eggs? Previous work by Dr. Moore found that the number of unburied eggs increases exponentially as you increase the number of salmon on the spawning ground (Moore et al. 2008). This happens because the more spawners there are, the greater the chance a later female will dig a nest over an earlier female’s nest, releasing many eggs into the drift rather than just the few that escape during the normal process of laying eggs.

This means that even a modest increase in the number of spawning salmon could have a large impact on numbers of unburied eggs that other stream fish can eat.

Overall, this work shows that: 1) the sizes and species of fish that benefit from salmon runs depends on the size of the salmon run; and 2) we should be concerned when annual returns of normally abundant salmon species (such as sockeye) are dwindling, because reduced egg-eating may handicap the growth and survival of smaller and less competitive fishes, including the juveniles of the species we love to fish for.