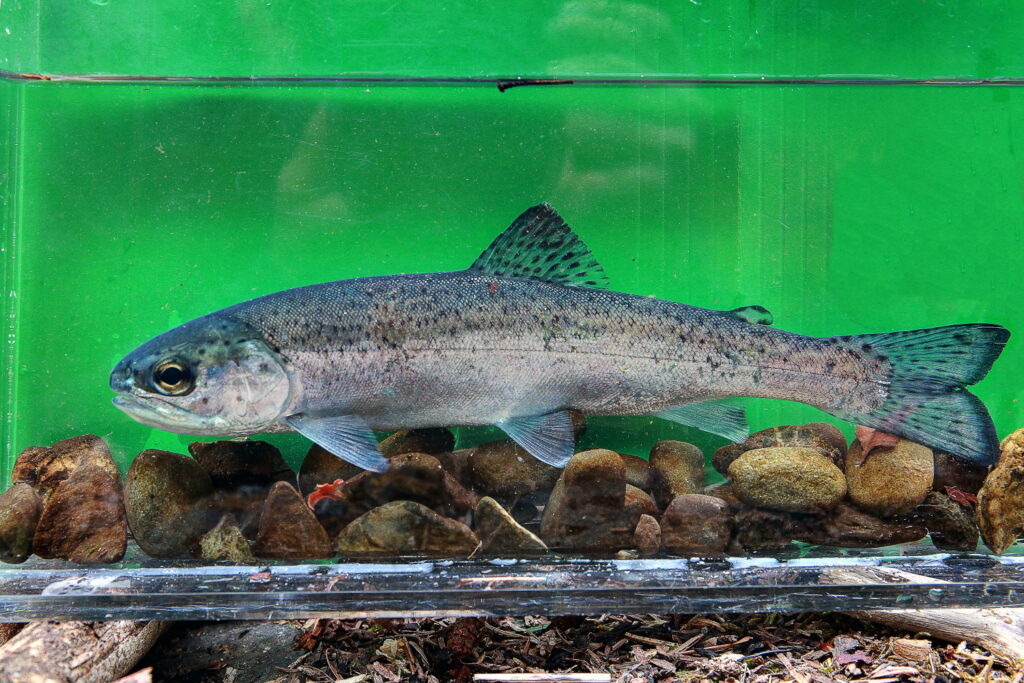

Image: John McMillan/TU.

Have you ever wondered how installing a dam, and later removing it, can influence the genetics of a population of migratory fishes? Because so many of our salmon and steelhead rivers have been dammed, and some old and unproductive dams are now being taken out or are proposed for removal, that is a question many fish scientists have tried to answer.

Today, we review a new study by Alexandra Fraik (Washington State University and several co-authors, including John McMillan (Steelhead Scientist for Wild Steelheaders United), that uses an extensive dataset to determine how dam construction and deconstruction influenced the genetics of steelhead and rainbow trout in the Elwha River.

Based on the scientific literature, we know barriers such as dams disrupt and block migration of fish up- and downstream, and because individuals that are separated cannot interbreed, over time disconnected populations should become increasingly genetically distinct.

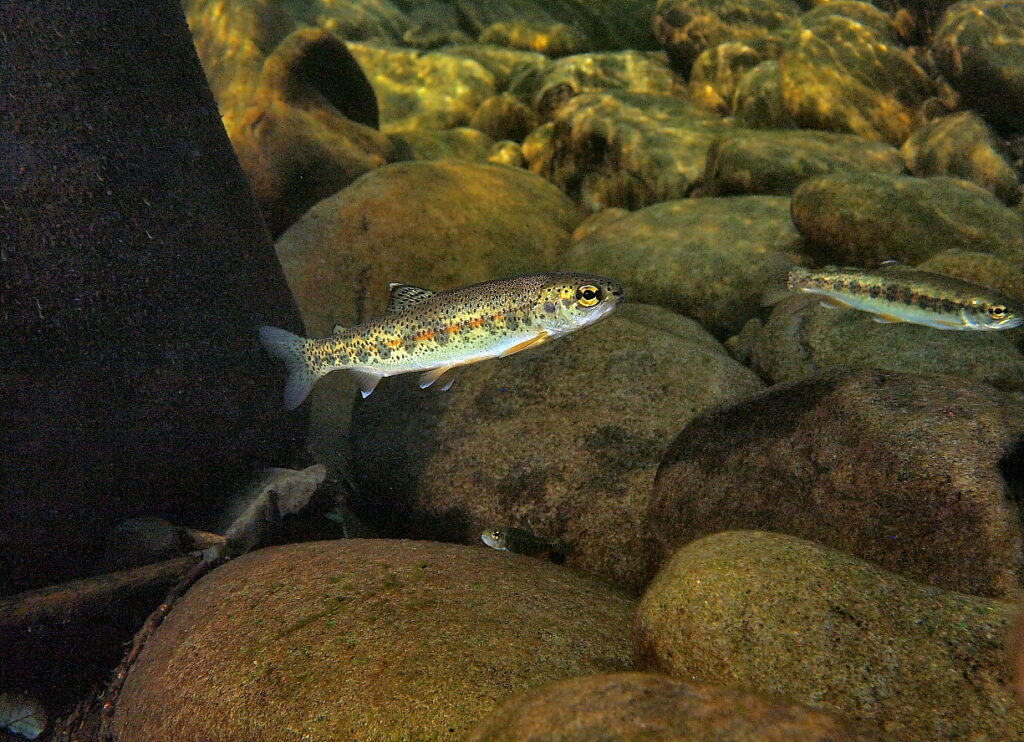

Image: John McMillan/TU

Indeed, we see this phenomenon above and below many natural barriers, such as impassable waterfalls. However, such natural barriers often have been in place for thousands of years. In contrast, on Washington’s Elwha River native salmon and steelhead populations have been disconnected for only a little longer than a hundred years.

Two dams were constructed on the Elwha in the early-1900s — the former Elwha Dam (approximately river-mile 5) and Glines Canyon Dam (approximately river-mile 14). Neither dam allowed fish to pass upstream, though research indicates some smolts were able to pass downstream, presumably during high water events when the dams released more water than normal. Today, after dam deconstruction in 2012 (Elwha) and 2015 (Glines Canyon), fish are once again able to move freely throughout the watershed and potentially interbreed.

Numerous biologists, scientists, and technicians (including McMillan) with the Lower Elwha Tribe, NOAA/NWFSC, Olympic National Park, USFWS, WDFW, and many others have collaborated on an intensive monitoring effort on the Elwha to assess the impacts of dam removal on salmon and steelhead. Part of this effort includes collecting DNA samples from juvenile and adult steelhead and rainbow trout. The study team analyzed over 1,200 DNA samples collected pre- and post-dam removal from 2015-2017.

While this study reveals many insights, today we focus specifically on four questions: (1) Were there genetic differences in fish below, in-between, and above the dams?; (2) Did pre-dam genetic structure change after dam removal?; (3) Are adult steelhead that are showing up in good numbers post-dam removal actually from the Elwha, or are they strays?; and (4) Are there genetic differences between winter and summer steelhead?

Image: John McMillan/TU

First, the research team identified three genetic clusters in the O. mykiss population, each of which was related to the presence of the dams. We refer to these three clusters as the below-, in-between, and above-dam populations, because the dams represented barriers to gene flow. As mentioned above, genetic differences tend to occur when populations are not interbreeding or are only doing so occasionally.

Certainly, some fish from above the dams were making it downstream. This has been documented in the Elwha River previously, and genetics of adult steelhead samples taken during dam removal suggested at least a few of them had their genetic origins above Glines Canyon dam. Still, overall these fish represented only a small fraction of the total population.

Second, after dam removal the genetic structure decreased from three genetic clusters to two, with the population in-between the dams becoming an admixture of individuals from above and below the dams. This occurred because the barriers to gene flow were removed, which allowed steelhead to return and spawn throughout the watershed. It also reconnected rainbow trout in the middle and upper river to steelhead that were formerly isolated below the dams.

Image: John McMillan/TU

Although the dams were present for over 100 years (20–25 steelhead generations), it is encouraging to see the rapid changes in the population structure. Steelhead have had access to habitat above the dam for only some two generations. We often think of dam removal as being of benefit to fish over the long term, as the environment recovers from a period of sediment transport and fish populations begin to recolonize and expand, but these results suggest there can be more immediate benefits to reconnecting fragmented populations of O. mykiss and other salmonids.

Third, adult steelhead returning to the Elwha River were primarily descendants of below-dam populations. No more than six fish were determined to be from a population other than in the Elwha (strays). However, most of the samples came from winter steelhead. Only seven samples were from adult summer runs. Winter steelhead were present in the lower river prior to dam removal and would have been the first to recolonize the Elwha River above the dam, which is likely why we found that genes from lower river fish predominated in the initial sampling of adults. This is likely to change over time.

Further, samples from out-migrating smolts have shown an increased proportion of genetic ancestry from the above- and in-between dam populations, suggesting that dams have not eliminated the ability of formerly land-locked rainbow trout to resume anadromy.

Fourth, there was a genetic difference between winter and summer steelhead. As we have discussed in previous Science Fridays (links here and here), research indicates there is a specific allele, GREB1L, that is strongly correlated with run timing in steelhead and Chinook salmon – with summer steelhead and spring Chinook salmon being GREB1L dominant. We found similar results in the Elwha. Most summer steelhead were GREB1L dominant, while most winter runs were not.

Image: John McMillan/TU

Interestingly, the above-dam population of rainbow trout exhibited the highest frequency of GREB1L; these fish likely hold the potential to give rise to summer steelhead. Summer runs were known to exist in the upper Elwha River prior to dam construction and snorkel surveys have revealed a very fast re-emergence of adult summer steelhead in the past four years. These results underscore the genetic variability within Elwha River O. mykiss and the value of landlocked rainbow trout sequestered above dams. But it’s important to remember that, despite the promising results to date, Elwha River steelhead are not yet recovered. It is still fairly early in the recolonization process and their population size, diversity, and spatial distribution is likely to ebb and flow as the environment sculpts the run timing and survival of returning adults and their offspring. But the results thus far are still impressive and there is reason to be optimistic that Elwha steelhead can continue their positive trajectory.

The value of this research is not limited to the Elwha. Thousands of barriers, from clogged or collapsed culverts to the massive dams on the Snake River, still exist and have contributed to the decline of wild salmon and steelhead across the West Coast. These results suggest that sufficiently abundant and diverse populations can rapidly recolonize a newly opened riverscape, increasing connectivity of the population and thereby creating new opportunities for interbreeding and resumption of former life histories (e.g., anadromy).

This study’s findings are consistent with other research on the impacts of dam removal on anadromous fish populations, and offer much hope for other depleted or even extirpated salmon and steelhead populations which have been disconnected — sometimes for a century or more — by dams. That’s why Trout Unlimited and Wild Steelheaders United advocated strongly for removing the old dams on the Elwha River, and why we are doing the same with respect to the four Lower Snake River dams (scientists have consistently found that taking out these dams is the only way to recover wild salmon and steelhead in the Snake to population levels that will be durable and fishable).

Habitat is the foundation for healthy populations of salmon, steelhead, trout and char — and a critical component of habitat is connectivity. Go here to learn more about TU’s work to reconnect watersheds, and here to learn more about our Snake River dams efforts.