This fall, for the first time since dam removal, recovering Coho Salmon numbers were able to support a Ceremonial and Subsistence fishery led by the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe

Washington’s Elwha River is home to all five species of Pacific Salmon, winter and summer steelhead, sea-run cutthroat, bull trout, dolly varden, resident rainbow trout, and Pacific Lamprey. Even among all the great rivers throughout the region, it was a remarkable salmonid crucible blessed with exceptional spawning and rearing habitat and cold, clean water fed by glaciers high in the Olympic Mountains. Because of this, the Elwha grew incredible salmon and steelhead. For example, its unique stock of Chinook ascended the Elwha’s Grand Canyon and were some of the physically largest outside of Alaska, nearly the size of the fabled June Hogs that once returned to the headwaters of the mighty Columbia.

For millennia, until a pair of illegal, impassable dams were built against their will in the early 20th Century, the watershed sustained the people of the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe. For a century, the Elwha Dam and the Glines Canyon Dam strangled the river and decimated salmon and steelhead runs. The two dams blocked access to nearly all the watershed’s historic spawning and rearing habitat and prevented sediment and woody debris from flowing downstream, leaving the lower river and delta starved for the rejuvenating gravel and log jams critical to healthy coastal river ecosystems.

Following decades of tireless advocacy and negotiation, both dams were removed between 2011 and 2014. At the time, it was the largest dam removal project ever undertaken anywhere in the world, a record that will stand until the removal of four dams on the Klamath River is completed in the coming year.

Above: Drummers from the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe perform at a celebration for the start of the fishery, which was held on Indigenous People’s Day. This was the first tribal fishery on an undammed river in over a century. Image: John McMillan

The Elwha’s transformation since the dams came down has been astounding. In the first few years following dam removal, sediment flushed from the former reservoirs in a muddy torrent, suppressing aquatic insect life and nearshore kelp beds for a short period of time. Resident fish in the river’s mainstem were killed, some sections of spawning gravel were temporarily buried, and the newly free-flowing river washed out a section of road below Glines Canyon.

But in the years that followed, especially during winter high flows, the Elwha continued to scour away the trapped sediment and transport the material downstream.

Quickly, the mobilized sediment began rebuilding the Elwha’s delta habitat. Nearshore species like sand lance and Dungeness crab recolonized the restored habitat and expanded their populations. In fact, crab populations have grown enough to support a modest fishery. Aquatic invertebrates are rebuilding their numbers throughout the lower river. Salmon and steelhead are returning to historic habitat above the former dam sites and reestablishing their populations at varying rates. The Elwha’s Bull Trout are getting bigger. Lamprey have recolonized former habitats and are flourishing. Research shows that bird numbers in the watershed are also improving as the ecosystem is restored.

Image: John McMillan

Almost immediately after dam removal, summer steelhead reemerged from the populations of native rainbow trout trapped above the dams in numbers that stunned scientists, a profound example of resilience celebrated in Shane Anderson’s inspiring film “Rising from the Ashes.”

More recently, Coho Salmon numbers have been steadily, and substantially, rebuilding. In October 2023, for the first time since the dams were finally gone, run counts have grown to a point where comanagers at the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, the Olympic National Park, and the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife could proceed with a limited tribal Ceremonial and Subsistence fishery.

The 1974 Boldt Decision, which outlines fishery co-management in Washington state, is structured in a way that supports the special treaty significance of Ceremonial and Subsistence fisheries ahead of larger sport and commercial fisheries.

The fishery is a profound milestone in the history of the Elwha watershed’s ongoing recovery. Far beyond the small number of fish harvested, it is a testament to the partnerships and dedication required to set the Elwha on this path towards recovery and further proof of the ability of rivers and native fish populations to heal following dam removals. The fishery is a celebration of the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe’s caretaking and connection to their home waters and a reason for all of us who work to restore free-flowing rivers to pause and remind ourselves why this work is so important.

Image: John McMillan

Elwha Coho are Rebuilding Numbers and Diversity

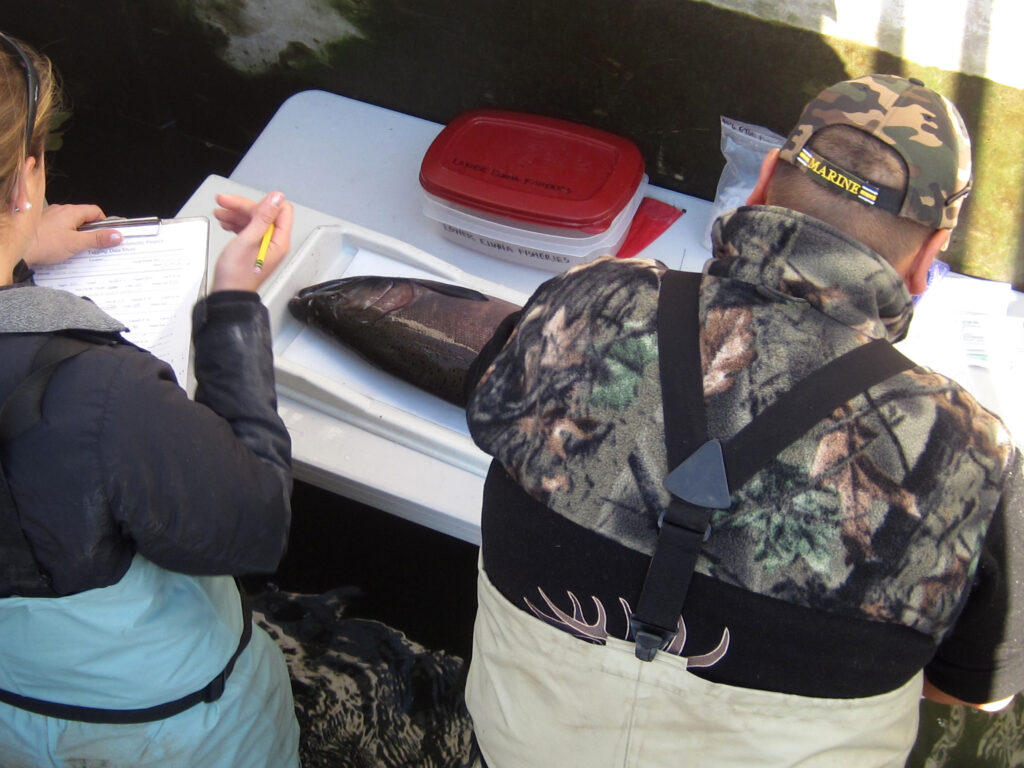

Scientists and comanagers track, forecast and corroborate Elwha River fish counts through snorkel surveys and redd counts, electrofishing, tagging and tracking fish, test fisheries, smolt traps and seines, and the use of sonar in the lower watershed. This extensive monitoring regime following dam removal has documented steadily improving Coho populations and Coho successfully using habitat upstream of the former dam sites.

For example, in a recent guest blog post, John McMillan wrote about new research showing Chinook, Coho and Steelhead reasserting crucial population diversity in a pair of key Elwha tributaries.

Pre-season forecasts estimated approximately 7,000 Coho would return to the Elwha this fall, evenly split between hatchery and wild fish. Coho numbers have grown substantially in the last four years. For example, in 2019 only 2000 Coho returned to the river based on sonar counts.

Image: John McMillan

To keep within recovery goals and limit impacts to Summer Steelhead, Fall Chinook and Chum Salmon, the Ceremonial and Subsistence fishery was limited to a harvest of 400 fish and the lower three miles of the Elwha River. Following an opening ceremony held at the river, the short fishery began on Indigenous People’s Day and continued through the end of October. During the first two weeks of the season, fishing was limited to rod and line methods. A traditional set net fishery, near the river mouth, was held during the last week. Caught fish were documented with catch cards and reported to Tribal fishery managers.

In the end, a total of 177 Coho were harvested by 151 registered anglers. Anglers caught and released 26 Coho and a handful of other species.

Lessons Learned

“It is really exciting to see the fruits of our labor and signs of recovery,” said Matt Beirne, the Natural Resources Director at the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe. Beirne has worked for the Tribe for nearly thirty years and has been involved with the planning and implementation of dam removal and worked closely with the subsequent fish recovery and efforts led by his colleague Mike McHenry.

Aside from their extensive work monitoring salmon and steelhead populations, the Tribe has been building log jams in the lower river and reintroducing fish to tributaries and mainstem sites upstream of the former dam sites.

Image: John McMillan

The Tribe operates a conservation hatchery program that was used to preserve Coho populations and basin-specific genetics while the dams blocked the river. In the years immediately preceding dam removal, and for a number of years since, salmon from this program were moved into key locations above the dam sites to jump-start recolonization of the river. Today, alongside fish naturally finding their way upstream of the former dams, the offspring of the planted fish are successfully utilizing the habitat as juveniles and returning adults.

To give salmon and steelhead recovery the best chance possible, the Tribe and comanagers established a fishing moratorium in the years following dam removal. This pause in harvest has been extended multiple times and is expected to continue in the years to come for many species as populations continue to reestablish abundance and diversity. The Coho fishery was the first opportunity to carefully target the population that has been showing the strongest recovery, but it was kept very short to limit any incidental impacts on Chinook and steelhead returning in September and the Chum Salmon arriving after the Coho. The use of sportfishing equipment gave larger numbers of tribal members an opportunity to participate in the fishery.

A little over half the allotted number of salmon were harvested by the end of October. Beirne noted that Coho returns, especially among hatchery fish, were lower than expected in a number of coastal systems this fall. The rivers on the Olympic Peninsula, Willapa Bay and in the Chehalis system saw in-season harvest reductions for Coho. Beirne also noted that the weather was dry in October and the Elwha didn’t see a sizable bump in flows in October, which might have limited the number of fish entering the system during the short season.

“Overall, the season was really positive and rewarding,” Beirne said. “Everywhere you looked, people were smiling and enjoying their time on the river again. There were youth who had never fished the Elwha before, and other Tribal members who spent entire days on the water, whether they caught fish or not, happy to be on the river again.”

Beirne explained that comanagers gained valuable experience operating the fishery and the data collected will help inform future seasons when forecasted returns support a fishery again. Beirne cautions that recovery remains the priority. “We’re hoping to continue the fishery, and even expand the scale so more people can participate,” he said, “but it all depends on the numbers.”

Image: John McMillan

“We are salmon people”

Vanessa Castle is a Natural Resources Technician for the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe. In that role, she splits her time between the river and forest, working on fish population monitoring, trapping and tracking animals for the Olympic Cougar Project, and youth education programs where young people are taught outdoor skills and learn about regional wildlife and ecosystems. She is also a member of the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe and has fished the Elwha River her entire life. She was taught to fish by her mother, a commercial fisherwoman who fished the Elwha until the dams devastated salmon populations to such an extent that she was forced to leave her home waters and shift to ocean fisheries.

Castle fished the opening day of the October Coho fishery with her entire family. It was the first time in twenty years they were all able to be on the Elwha fishing together again.

“We are salmon people. Being able to harvest food from the river again is healing for our people and our families,” Castle explains. “Our people lived next to the river for a reason. The river sustained us, and it will again in the future as long as we take care of it.”

[Listen to a presentation Castle gave earlier this year on “Ecosystem Restoration and Cultural Renewal in the Elwha Valley” as part of the University of Washington’s School of Aquatic and Fishery Science’s Bevan Seminar Series]

“Right now, the river is in a restoration phase. It is a long journey, it is working, and we are committed to it, but this phase has created a generational gap between those who remember fishing on the Elwha and those who haven’t had the chance yet,” she said. “Before the fishery this fall, there was a whole generation of young people who’d never caught a fish here before. Over and over again, during the fishery, I saw young people catch their first salmon ever.”

Reconnecting the young generation to the Elwha River was a blessing. Castle also had the opportunity to help Tribal elders reconnect to their home waters and first food source. A skilled angler, Castle caught her personal limit of coho soon after the season opened. She fed her family with those fish, but fishery managers saw an opportunity for a few Tribal members to also fish on behalf of tribal elders who weren’t able to participate in the fishery.

Image: Courtesy of Vanessa Castle

“Being a designated fisher was an amazing experience. Sharing fish with our elders has always been an important part of our traditional fisheries,” Castle explained. “I’d bring salmon to their door. Many cried tears of joy. Many gave me a huge hug.”

The Elwha’s recovery is ongoing. When dam removal began, many biologists and managers expected full recovery to take decades. There is still a great deal of work to do. Resources and investments will continue to be needed to ensure the extensive monitoring and ongoing restoration work can continue.

The remarkable growth of Coho is a promising sign of progress. The inaugural Ceremonial and Subsistence fishery was further proof of the restoration vision that started long before the first pieces of concrete began to be chipped away from the dams blocking the river.

Reflecting on the fishery, Castle looks to the future. “We know there are lots of people who love the Elwha River and fished it before and look forward to fishing it again one day, too. It is why all of us are working so hard to heal the river. We are thankful that we were able to fish to feed our families and begin our healing. We hope to fish again as long as Coho numbers continue to grow, but we’re also looking forward to standing with everyone at the river and enjoying what it has become.”