It’s December and winter steelhead season is officially underway across much of the Pacific Northwest. While this would normally be the time to share a touch of holiday cheer and offer congrats to those who have already landed a steelhead, this year is bittersweet for anglers on the Olympic Peninsula (OP).

Last week, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) enacted new regulations coast-wide that fundamentally change the way we pursue steelhead, with the stated goal of reducing our encounter rates on these last, best wild runs here in Washington. The new regulations include a ban on fishing from boats and the use of bait, requires the use of single-point barbless hooks, and bans retention of rainbow trout.

It’s a disappointment for the 2020-2021 season to be sure, but those who can think beyond the brim of their hats will know it’s the best call for the fisheries and communities that depend on them.

A few weeks back, WDFW held a virtual townhall to inform anglers that returns of wild and hatchery winter steelhead are forecast to be very low for the OP, Grays Harbor, and Willapa Bay regions. The situation isn’t pretty, and it’s more dire for some populations than others.

Unfortunately, a series of very poor ocean years has further depleted the stocks of wild steelhead and things are unlikely to turn around soon based on expected smolt survival out in the big blue. At this townhall, WDFW proposed a series of potential regulation changes that ranged from full closure of all river systems to more conservative measures that would reduce angler efficiency but also allow a longer fishing season, with a goal of ensuring more steelhead make it to the spawning grounds.

We Saw This One Coming

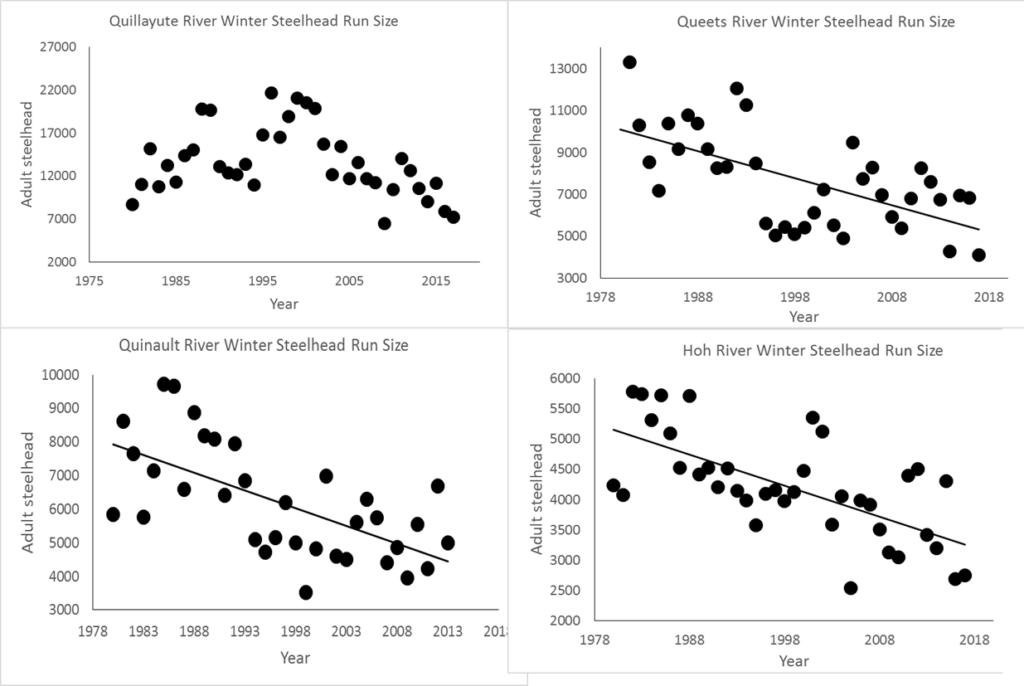

These small run sizes and forecasts shouldn’t be a surprise to those familiar with the OP. The situation has been building over the past 10-20 years. Declining stocks were first brought to attention with a status review of steelhead stocks and their management by the Wild Steelhead Coalition in their 2006 report. Then came Shane Anderson’s movie Wild Reverence in 2014, which underscored the seriousness of the declines and warned of a potential listing under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). And, as we have written about over the past six years in our Science Friday series, wild winter steelhead populations have been in long-term decline since 1980 in the Queets, Hoh, and Quinault Rivers. While the Quillayute population has overall performed better, it too has declined steeply since the late 1990s (Figure 1).

The declines are why we, and other organizations and anglers, including a 2015 WDFW North Coast Steelhead Advisory Group, for years have advocated for a more measured approach to modifying sportfishing regulations and considered ways to minimize our impact on catch and release fisheries for winter steelhead.

These declines are also why coastal tribes, the Coast Salmon Partnership, The Nature Conservancy, TU, Wild Salmon Center, Regional Fishery Enhancement Groups, and Conservation Districts have invested heavily in habitat restoration in several of these watersheds. Even though many of these basins have a high proportion of their watersheds in the Olympic National Park, a lot of important winter steelhead habitat is found outside of the park. Restoring that habitat is critical to a sustainable future for wild winter steelhead.

Although the regulations have raised some controversy, we believe the evidence overwhelmingly supports implementing more conservative sportfishing regulations on the OP.

Image: John McMillan/Trout Unlimited

This was not an easy decision for WDFW, and it is bittersweet for anglers. Worse, these changes to the way we pursue steelhead on the OP by themselves will not turnaround these declining runs. While we still get to fish and will have to adjust to these new regulations, the populations are still on the decline.

Still, if we are serious about fishing for OP wild steelhead into the coming decades, we will focus less on what we get this year and more on how we can develop a plan that will address the threats and help rebuild the depleted populations.

While we recognize these new sportfishing regulations fundamentally change the way we fish for steelhead, we see several clear benefits to WDFW’s approach, including keeping the best advocates of the fish on the water, us anglers.

The Trends Are Clear to Anglers and Scientists

To execute the OP steelhead fishery at the status quo and not take emergency actions this year would increase the likelihood of an ESA listing, which means game-over for anglers. As mentioned earlier, most of our famed OP winter steelhead populations are in decline (Figure 1). Hoh River steelhead have frequently missed their escapement goals for the past fifteen years and many of the lowest run sizes on record have come in the past five to ten years. Further, there is strong evidence that the early-timed component of wild steelhead in the Sol Duc River, which returned from November through early January, have been greatly depleted (Bahls 2001).

If these trends aren’t reversed soon the entire OP Distinct Population Segment (DPS) will be listed under the ESA and the fisheries will close for an indefinite time period. This same thing happened in 2007 to the winter steelhead fisheries in Puget Sound, so avoiding that outcome should be a priority.

It took about two years from petition to decision for the listing of steelhead in Puget Sound, which means we need to act meaningfully and swiftly to stave off a listing. Adopting these more conservative fishing regulations is the only action steelheaders can take with potential to immediately help wild steelhead.

Image: John McMillan/Trout Unlimited

It’s on Foot from Here

While the ban on fishing from a boat is the most controversial change, this is the WDFW’s most effective tool to reduce encounter rates and provide a longer fishing season. We understand the strong opinions on either side, but WDFW’s own data shows that more steelhead are being caught and released by boat anglers.

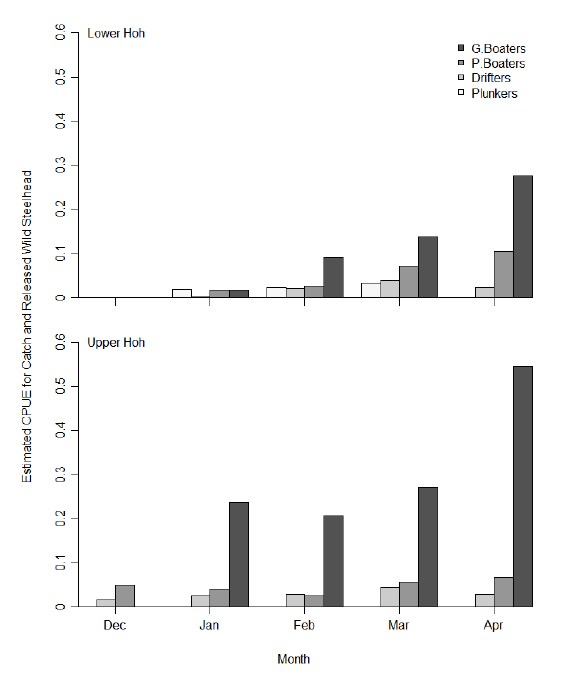

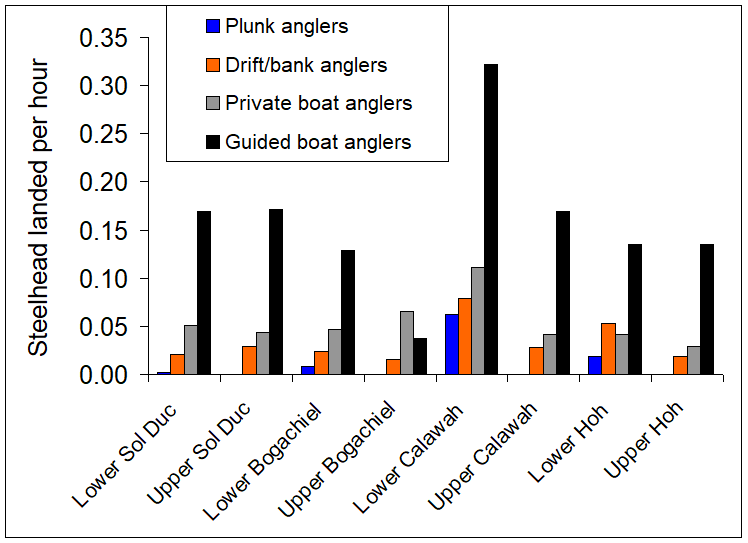

In a WDFW study on the Hoh River from 2015, it was estimated that boat anglers had a catch-per-unit-effort (CPUE) that was 3-5 times higher than bank anglers (Figure 2). Similarly, high rates exist in the Quillayute system (Figure 3). Owing to the high CPUE, WDFW estimated that every steelhead that escaped to spawn in the Hoh in 2015 was caught and released, on average, 1.4 times by anglers. After discussions with numerous other scientists, the OP encounter rates appear to be very high relative to other populations on the West Coast with similar creel data, perhaps even higher than any other population. Although we expect encounter rates to increase for bank anglers, the overall encounter rates should be greatly reduced, resulting in lower mortality rates and sub-lethal effects such as less stress associated with handling and fighting, which in turn equates to more productive fish on the spawning grounds.

Additionally, a more conservative fishery provides a buffer in case the pre-season run forecasts are overestimated, which is common for OP steelhead. Pre-season forecast models are fraught with uncertainty because it is very difficult to predict how fish survived in the ocean, and higher encounter rates could lead to populations missing their escapement goals.

If allowed to fish out of a boat, the angling season would have to be substantially shorter to account for the increased efficiency and still provide a buffer for an inaccurate preseason run forecast. While the notice is short, we believe a longer season from the bank, even using less efficient methods, is a win for anglers, steelhead, and rural economies. It aligns conservation and angling opportunity and maximizes the season over which anglers will contribute to the economies in communities like Forks.

It Takes All of Us

Supporting these conservation measures is important if steelheaders want long-term collaboration with tribes to rebuild wild steelhead. Through hard work and communication between WDFW Region 6 staff and the tribes, co-managers were able to reach agreements this year that include serious concessions that will improve escapement of wild steelhead.

The Region 6 staff provided additional information about these regulation changes in this blog post, including the data used to support this decision, and the Steelhead Harvest Management Plans from both the Hoh Tribe and Quileute Tribe.

While we understand the frustration of sudden changes in angling regulations, solely blaming tribes for the decline of these runs and inciting division will not help solve the problem. The tribes have a right to fish. We have a privilege. Let’s not forget either that the tribes have long carried the burden of protecting and restoring habitat. If their salmon and steelhead populations collapse, they can’t pack up and move to another river.

Image: John McMillan/Trout Unlimited

While we as anglers have made some substantial changes for our upcoming season, it is only a one-year fix. A longer-term plan is needed to rebuild the populations and achieving that goal will require strong collaboration between co-managers. We won’t get that by insulting a group of people who also cherish wild steelhead and salmon and the rivers they inhabit. Rather, we should be natural allies in an aligned effort to rebuild these magnificent populations.

We appreciate that the emergency response is a major undertaking for WDFW and the co-managers, and that these rules are controversial among some anglers, but that fact does not diminish their necessity.

To recap, the following are some of the concerns driving these new conservation-minded sportfishing regulations from WDFW:

- significant changes in the health and abundance of wild steelhead

- large public investments in steelhead habitat protection and restoration

- the surging popularity of steelhead fishing

- the swelling ranks of steelhead guides on the OP

- growing support for conservation of wild steelhead among all sport anglers

- new scientific information emerging regarding what wild steelhead need to thrive

Western Washington is blessed to still have rivers including the Hoh, Sol Duc, Calawah, Bogachiel and Queets Rivers that have sizeable wild steelhead populations that can, if carefully managed, continue to support recreational and tribal fisheries.

The OP represents the best last place for wild winter steelhead in Washington state. We have one last chance to get it right for our state fish. If that means sacrificing some opportunity now to help steelhead in coming years, we at Wild Steelheaders United are willing to absorb that impact. We empathize with those that disagree, but these fish have given so much to each of us that we think it’s time to put the fish first.

Plus, if we don’t do it now, science tells us we likely won’t even have the chance to later.