As salmon and steelhead return to the Klamath following dam removal, we look at the work being done to track their populations and the plans guiding their reintroduction to historic habitat

One of the truly magical moments of dam removal is when the fish start to return to their historic, reconnected habitat. It is a tangible moment in a process that can take decades to accomplish, and it confirms our hopes for these rivers. The Klamath is in this joyful, magical moment now.

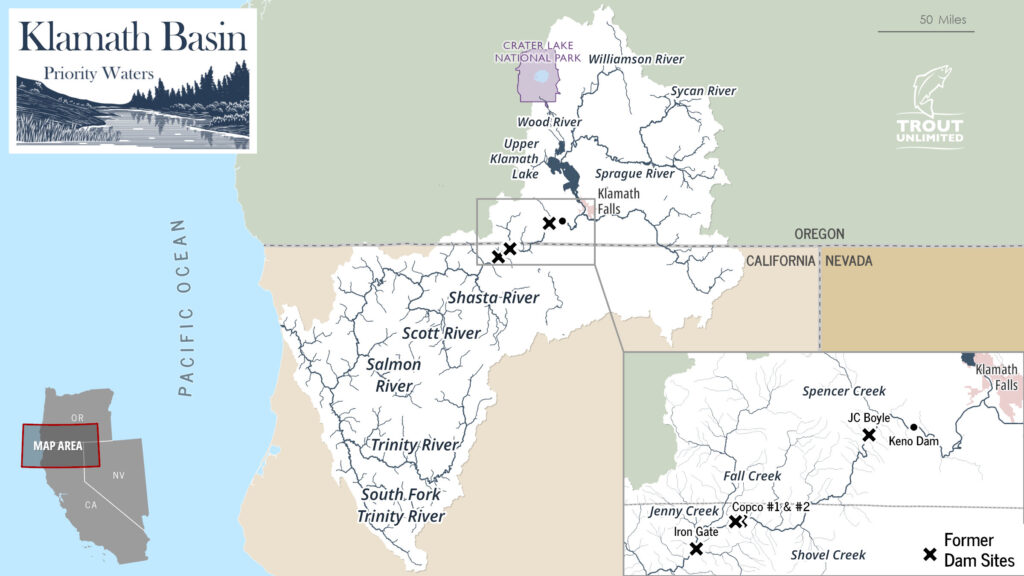

The final barriers came out in late August and the first salmon, a fall-run Chinook, was observed on sonar passing through the former site of Iron Gate Dam soon after. In October and November, over one hundred fall-run Chinook were seen spawning above the dams, including all the way into Oregon. Smaller numbers of coho and steelhead have also been physically observed above the former dams and preliminary data from sonar has documented thousands of fish migrating through the former Iron Gate site.

With the immediate arrival of salmon, we thought it would be worthwhile to provide an update on fish numbers and revisit the monitoring and reintroduction plans guiding the efforts to rebuild salmon and steelhead populations in the Klamath basin following dam removal.

Image: Katie Falkenberg/Swiftwater Films

Order of operations – When should we see different species arrive?

In the Klamath, fall-run Chinook salmon typically return from early October through early December, and as such, they were the first salmon species observed passing upstream of the former dam sites and recolonizing the reservoir reach.

Summer steelhead, including the Klamath’s famous half-pounders, enter the river July through September and are followed by winter steelhead. Numbers slowly build through winter, with peak steelhead spawning occurring in February to March. Coho runs generally pick up around November and go through December. Pacific lamprey should start to return shortly thereafter, beginning in December and continuing through May.

During runoff in late spring and early summer, spring-run Chinook will enter the basin from March to July. Historically, along with Klamath steelhead, they ran far upstream into the basin’s headwater streams above Upper Klamath Lake, but today the remaining intact populations of these fish are limited to lower tributaries. The South Fork Trinity and Salmon Rivers contain the biggest portion of remaining populations, and it is unknown how long it will take for some of these lower-river fish to find their way back to the historic habitat further upstream.

Despite historically low abundances of all salmon and steelhead in the Klamath, only coho salmon are currently listed under the Federal Endangered Species Act. Klamath-Trinity River spring-run Chinook are listed under the California Endangered Species Act.

Monitoring plans

For fish reintroduction to be a success, it is critical for managers to understand when and where fish arrive, the habitats they are utilizing, and how their populations are growing.

The Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW) and the Klamath Tribes, and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW), published comprehensive reintroduction and monitoring plans that are now being implemented throughout the basin. The planning and implementation is happening through an extensive collaboration network that includes tribes, federal agencies, state agencies and nonprofits.

CDFW is operating weirs equipped with video recording equipment to count the number of each fish species returning to the Scott and Shasta Rivers, as well as Bogus, Jenny and Shovel Creeks. They are also counting fish returning to the Fall Creek hatchery.

The Karuk Tribe, Yurok Tribe and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service are conducting spawner and carcass surveys from Wingate Bar to the Oregon-California border as part of a longer-term dataset that will be critical for understanding the population responses to dam removal. Fish presence and passage monitoring surveys are being conducted by the Klamath River Renewal Corporation and their contractors throughout the historic hydroelectric reach using field surveys and eDNA sampling. Farther upstream, above the former JC Boyle Dam site in Oregon, ODFW and Klamath Tribes biologists are conducting fish presence and spawning surveys.

Additionally, a large team led by CalTrout is operating a sonar station at the former Iron Gate Dam site to count how many fish have passed. They will also be capturing and tagging fish with radio and PIT tags to monitor their movements upstream of the Iron Gate site.

All entities working on monitoring fish returns in the basin are committed to sharing data and their level of coordination is really impressive and commendable.

What have we seen so far?

The data collection seasons are only just beginning. Of those that have been reported, they are preliminary and will be extrapolated at the end of the season to estimate the true numbers of returns. With that said, here are some of the numbers that have been reported thus far.

Image: Swiftwater Films

By early January, ODFW biologists have counted over 182 fall-run Chinook and 81 redds in Spencer Creek. In the former-reservoir reach downstream of Keno Dam, they counted 179 fall-run Chinook over 150 redds, and 19 coho salmon.

CDFW biologists had observed over 100 fall Chinook on the video weir in Jenny Creek and 27 Chinook arrived at the Fall Creek Hatchery, which is located nearly eight miles upstream of the former Iron Gate Dam. Additionally, as of mid-November, CDFW had captured seven coho salmon at Fall Creek Hatchery. Five were stream-born (‘wild’) and two were hatchery origin fish.

CalTrout and their partners observed their first fish passing the Iron Gate Dam site on Oct 3 and, since September, have tagged fall-run Chinook, coho, and steelhead in the former reservoir reach. And, as mentioned above, preliminary data from sonar has documented thousands of fish moving through during late October.

As of late December, biologists from the Karuk Tribe, Yurok Tribe, and the US Fish and Wildlife Service have observed over 175 redds, 200 live fall-run Chinook, and 80 fall-run Chinook carcasses between the Iron Gate Canyon and the Oregon/California border. High turbidity and low visibility conditions downstream of the Shasta River confluence has prevented surveys between there and Wingate Bar.

Image: Katie Falkenberg/Swiftwater Films

Reintroduction Plans

In 2023, we put together a blog post looking at the planning being assembled to guide fish reintroduction and restoration after dam removal. Those plans are now finalized and being implemented in the coming years. They’re built around a combination of fish finding their way to habitat above the dams on their own, and, in the case of spring-run Chinook, juveniles being stocked upstream to reestablish populations.

Most salmon and steelhead adults return to the same tributary where they were born, but some percentage of each year’s run “strays” from their natal tributary. This means that as habitat becomes available after dam removal, scientists expect salmon and steelhead to spawn and recolonize that newly available habitat, as we’ve seen in Washington’s Elwha River and Oregon’s Sandy River.

Hatcheries have been used for decades to support salmon and steelhead populations in the Klamath. As populations rebuild, new and existing programs will have various roles in the coming years, depending on species. Historically, like many systems, fish from outside the basin were stocked in the watershed to supplement runs decimated by the dams. Today the fish being planted are using broodstock from Klamath basin populations.

The Fall Creek hatchery, which was built as a replacement to the Iron Gate hatchery at the former dam site, plans to produce 3.25 million fall-run Chinook salmon of various juvenile life stages and 75,000 yearling coho salmon to supplement the populations. These levels of production are planned for the next 8 years, at which time it is expected that the populations will no longer need hatchery support. CDFW plans to release various ages and sizes of juvenile salmon to encourage out-migration at different times of the year, in an effort to better replicate natural fish behavior and life history diversity.

The Iron Gate Hatchery used to produce steelhead, but that program ended several years ago and will not be reinstated.

Image: Swiftwater Films

The Trinty River Hatchery in the lower Klamath River produces spring-run and fall-run Chinook as well as coho salmon and steelhead. Some of these fish may stray into the newly available habitat at or upstream of the former reservoir reach.

Both Oregon and California intend to rely on volitional recolonization above the former dams for all species except for spring-run Chinook. This means that fish will not be actively moved to the former reservoir reach or upstream. All species will be given several generations to recolonize, approximately 12-15 years. After which, some active relocation may be considered if managers believe populations aren’t being established quickly enough without further intervention.

Spring-run Chinook are the exception because their current distribution is limited to the Trinity River in the lower Klamath, which is over 100-miles downstream of the former reservoir reach, and because their population is relatively small. For these fish, the plan is to rear Trinity spring-run Chinook at the Klamath Hatchery in Oregon and then relocate approximately 10,000-50,000 smolts or sub-yearlings to upstream tributaries. This should help the fish acclimate to upper river reaches and home back to these locations when they return as adults to spawn, thus setting up a sustaining population across their historic habitat the upper basin.

To prepare for this effort, researchers at UC Davis have worked closely with the Klamath Tribes, NOAA, ODFW and TU staff to release tagged spring-run Chinook smolts into multiple locations upstream of Upper Klamath Lake. They tracked the juvenile fish through the system to confirm that outmigrating smolts are able to navigate the lake and pass successfully downstream through the Link River and Keno Dams.

TU restoration work upstream of the dams

For years, as the effort to reconnect the Klamath unfolded, Trout Unlimited staff were also busy restoring habitat throughout the upper Klamath basin. This work benefits resident native fish, including threatened Bull Trout, along with returning anadromous species. It also improves groundwater levels, water quality and provides watershed resilience following wildfire.

Image: Evan Bulla.

To prepare for dam removal and the return of salmon, steelhead and lamprey, TU staff partnered with the NOAA Restoration Center and the Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission to map and prioritize the habitat restoration actions that should be undertaken first in the reservoir reach. In the Oregon legislature, we’ve worked to help secure funding for ODFW’s monitoring effort.

After such a long absence, it is inspiring to see the first salmon arrive this fall. Many of these upstream habitats are places that have not had anadromous fishes for over 100 years but will be critical to rebuilding the Klamath’s salmon, steelhead and lamprey populations. To give these fish the best chance possible, TU’s Klamath Falls team is working hard to expand the scale and impact of critical restoration work throughout the Upper Klamath headwaters and the reservoir reach.

Learn more: Visit Klamath River: Reconnection and Restoration to explore a new StoryMap of the dam sites and watershed, a timeline of the quarter-century effort to reconnect the basin, and resources for TU members and supporters to understand the intertwined story of the long road to dam removal and the restoration work underway upstream in the Klamath’s tributaries and Upper Basin.