Image: Aaron Penvose/Trout Unlimited

TU is helping steelhead and bull trout in Washington’s Icicle Creek by moving truck-sized rocks

There’s no magic bullet for wild steelhead conservation. Sometimes it’s about flows, other times it’s about habitat. Integrating efforts to enhance flow and restore habitat often delivers synergistic benefits for fish, which is why Trout Unlimited has an extensive program that does just that throughout the West.

Other times it’s about resource management — TU brings our considerable scientific and policy expertise to this conservation front, too.

But on rare occasions – and only after careful study and consultation – wild steelhead conservation is about standing back at a safe distance and letting thoroughly trained demolition professionals bust up rocks the size of F-150s.

Take Washington’s Icicle Creek, for example. Icicle Creek has the cold, clean water that fish like steelhead and bull trout need. From its origins high on the eastern edge of the Cascade Crest, this stream tumbles down through the Alpine Lakes Wilderness and the Wenatchee National Forest before joining the Wenatchee River near the self-styled “Bavarian Village” and frosty beer steins of Leavenworth.

As with almost any stream of consequence for salmonids in the Columbia Basin, however, Icicle Creek has its fair share of familiar challenges: cumulative demands on water from agriculture, municipal use and a large national hatchery facility are just some of the factors that take a toll on flows and fish here. A broad-based effort to re-calibrate and balance those demands and accommodate the needs of fish and tribal and recreational fishing has been under way for years.

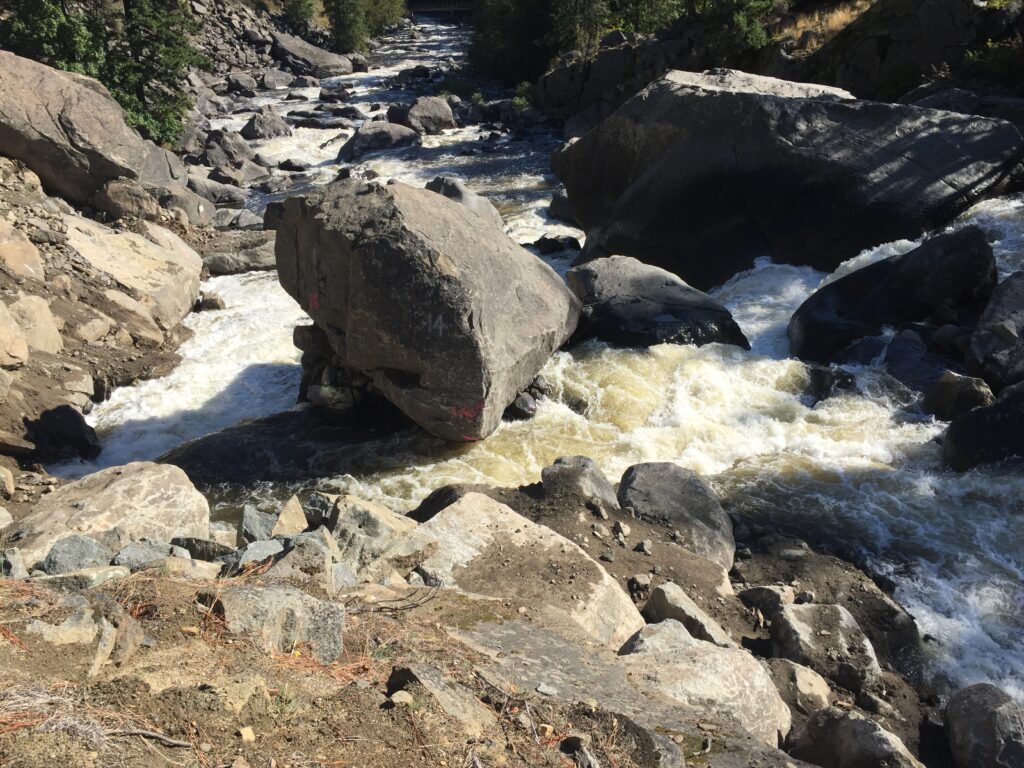

Then there’s that Boulder Field.

Image: Aaron Penvose/Trout Unlimited

About six miles upstream of Leavenworth, a series of giant granite chunks stacked in and around the creek channel creates some 25 vertical feet of barrier which, under most flow conditions, prevents steelhead and bull trout from navigating further up Icicle Creek. The Boulder Field has fomented years of debate about what can be done to reduce its impact on fish migration.

This collection of enormous rocks likely settled in this particular spot through a mix of ancient glaciation and more recent road-building activity dating to the 1930s. But the primary reason people care about the Boulder Field today is what’s upstream of it — some 26 mainstem miles and additional tributary miles of largely undeveloped public lands habitat well-suited for ESA-listed steelhead and bull trout.

TU’s Washington Water Project Manager Aaron Penvose is a water guy. With years of experience guiding large-scale irrigation and water efficiency upgrades and various other instream flow strategies throughout the Upper Columbia Basin, his steady approach usually starts with getting water back in the stream, then helping the fish figure it out from there. But in Icicle Creek, he saw something different. To help steelhead in the Icicle access all that high-quality habitat upstream of the Boulder Field, you might have to embrace more aggressive tactics. You might have to move some rocks. Big rocks.

“Philosophically it finally settled in my head years ago that getting in there and restoring passage was the right thing to do,” Aaron says. “Then let the stream and the fish sort things out over time.”

This conviction led Aaron to develop a construction project for the Icicle Creek Boulder Field which would, in fact, deconstruct much of it. In the summer of 2020, after more than ten years of planning and preparation, work crews launched the construction phase.

Image: Aaron Penvose/Trout Unlimited

The project involves (1) “modification” of several boulders using heavy hydraulic rock drills and low velocity charges placed inside boulders with water that break them up; (2) placement of other boulders; and (3) excavation of four pools along the channel providing improved fish access up the incline.

In addition, the City of Leavenworth’s municipal water intake was modified and fitted with a new ESA compliant self-cleaning screen system. Instream work was completed in October of this year.

Penvose cautions that progress — meaning more fish utilizing the habitat above the Boulder Field — should not be taken for granted, nor should we expect thousands of steelhead and bull trout to pour into the Alpine Lakes Wilderness like Black Friday shoppers into a Walmart.

“The project isn’t creating a superhighway or a fish ladder,” Penvose told the Wenatchee World. Instead, the objective is to create or restore conditions at the site that will allow fish to access upstream habitat at times of the year advantageous to them and, importantly, in flows they would naturally take advantage of. “We’re planning for some adaptive management also,” Penvose says.

The solution for steelhead and bull trout on Icicle Creek, as it often is in important salmonid streams, boils down to habitat + water + science-based management. In this case, with a little twist — some extensive boulder busting.