Arbitrary management: the March 15th hatchery-wild cutoff

Quality data is the foundation of quality fisheries management and should be the cornerstone shaping decisions regarding fishing seasons, hatchery and wild impacts, and recovery of wild steelhead populations.

As such, it is jarring whenever an arbitrary metric is used to broadly guide fisheries management, despite the availability of data and tools to better inform those decisions.

In Washington, one of the most striking examples of an arbitrary decision point is the reliance on March 15 as the cutoff date between hatchery and wild steelhead spawners in many watersheds. While March 15 might be a consistent and convenient distinction between the hatchery and wild fish monitoring seasons for Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) biologists and managers, this oversimplification has significant consequences for the quality of information informing steelhead hatchery impacts, wild fish abundance, and angler opportunity.

Why March 15th?

Steelhead are known for their elusive nature. They can be a challenging fish for anglers to catch and just as difficult for biologists to count. The challenges of monitoring wild steelhead populations get even more complicated when hatchery fish are present.

First, steelhead often return when rivers are high and turbid, making weirs nearly impossible to operate and maintain, snorkel surveys difficult, and visual observation challenging. Second, steelhead are repeat spawners, and as such, traditional spawning ground surveys used for salmon, which rely on fish carcasses to identify adipose clipped steelhead and to determine hatchery and wild ratios, are not possible.

To sidestep these challenges, Washington fisheries managers adopted the March 15 cutoff date to reduce the likelihood of counting hatchery steelhead in spawning surveys focused on enumerating wild steelhead. As a result of this policy, biologists do not even start counting redds until March 15 in many watersheds.

Top image: Wild steelhead jumping at Lucia Falls. Image: Greg Shields

Segregated Hatchery Programs

The central assumption of the March 15 cutoff date is that hatchery steelhead spawn significantly earlier than wild fish. On the surface, this assumption appears to hold up well for the segregated hatchery programs that have dominated hatchery steelhead releases in Washington for decades.

To increase the segregation between hatchery and wild spawners, WDFW has spent decades selectively breeding their Chambers Creek winter steelhead and Skamania summer steelhead stocks to facilitate early spawning. Currently, Chambers Creek stock steelhead typically spawn between late-November and January and WDFW does not spawn any of these fish in their hatcheries after the end of January.

The efforts of hatchery managers to manipulate and consolidate spawning timeframes in these populations seems to have worked. Recent modeling using in-hatchery data suggests that by selecting for early spawning fish, 99.9% of Chambers Creek early-winter steelhead from the WDFW hatchery programs review are expected to have spawned by March 15, with Skamania summer steelhead typically spawning even earlier (Hoffman 2017, Marston and Huff 2022).

| Hatchery Program | Date |

| Humptulips Hatchery | February 20 |

| Bogachiel Hatchery early winter | February 23 |

| Tokul Creek early winter | March 2 |

| Naselle Hatchery early winter | March 9 |

| Forks Creek Hatchery early winter | March 15 |

However, it is important to remember that this is modeled data. Additional data gathered in the field by monitoring programs is needed to verify the assumptions used in the models.

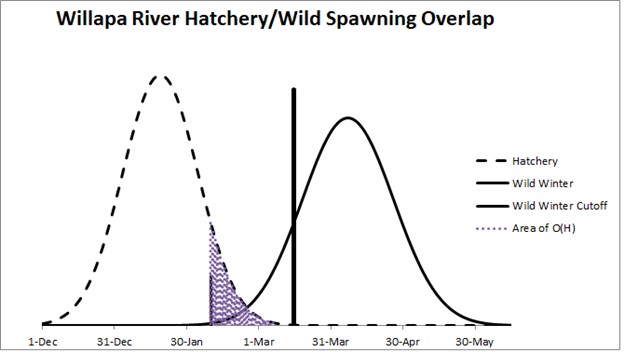

For example, outside of the hatchery setting, there is evidence that later-returning male Chambers Creek stock hatchery steelhead can remain on the spawning grounds for several months, waiting to spawn with wild females (Seamons et al. 2004, 2012). As shown in Figure 1, these segregated hatchery fish remaining in-stream will also be spawning with early spawning wild fish as well.

Findings like these show there is room, and a need, for additional work to verify and improve upon the assumptions utilized in the Department’s models and that a conservative approach should be taken when interpreting the results regarding both hatchery spawn timing in the wild, and the impacts on wild populations when hatchery fish aren’t harvested.

Integrated hatcheries

While the March 15 cutoff may have some utility for monitoring segregated hatchery programs, it completely breaks down with integrated hatchery programs. (These are often referred to as “wild broodstock” programs.)

In a well-run integrated program, broodstock is derived from both hatchery and wild fish gathered throughout the wild fish spawning window. Under this scenario, the goal is for the hatchery population to have a nearly identical spawn time as the wild population. For monitoring in these systems, the March 15 cutoff date is a completely invalid approach.

It is nearly impossible to mimic nature in a hatchery, and most steelhead production programs don’t attempt to. For example, while most wild steelhead smolts begin their seaward journey at age 2 or age 3, hatchery steelhead are almost always released as one year old smolts.

Most integrated programs do not fully encapsulate the wild fish spawning window of wild steelhead, which would require more egg-takes throughout the full length of time when fish are returning. Despite accelerated hatchery feeding regimes, it would also make growing the offspring of late-spawning fish up to size as one-year old smolts challenging. As such, it is not uncommon for integrated programs to spawn their fish earlier than the majority of the wild population.

For example, winter steelhead from the Bingham Creek integrated program on the Satsop River are typically spawned in the hatchery between late-February and mid-April (WDFW escapement reports). Under this scenario, a significant portion of the hatchery fish are going to spawn in both the hatchery and in the river after March 15, so the cutoff data cannot be used with any confidence to account for the timing of hatchery and wild fish on the spawning grounds.

Even though the assumptions with the March 15 cutoff date are completely invalid for integrated hatchery programs, WDFW is still utilizing it in the Chehalis River basin where they currently release steelhead from five integrated hatchery programs (Wynoochee, Satsop, Skookumchuck, Newaukum and upper Chehalis River). This has real consequences for both wild fish and anglers.

The wild fish problem and angler impacts

Steelhead populations across western Washington naturally evolved to have a wide range of spawn timing, but populations in rain-driven streams and tributaries generally spawn earlier than those in snow-driven streams or large mainstem rivers (Table 2).

| River | Percent Wild Steelhead Spawning Before March 15 | Eco-type (rain or snow) |

| Sauk River | 0.7% | Snow |

| Stillaguamish River | 1.3% | Snow |

| Green River | 1.3% | Snow |

| Pilchuck River | 1.9% | Rain/ Snow |

| Snohomish/ Skykomish | 2.0% | Snow |

| Snoqualmie River | 2.1% | Snow |

| Clearwater River | 3.5% | Rain/ Snow |

| Dungeness River | 3.9% | Snow |

| Skagit River | 5.0% | Snow |

| Nooksack River | 6.2% | Snow |

| Wynoochee River | 6.3% | Rain/ Snow |

| Bogachiel River | 8.4% | Rain/ Snow |

| North River | 10.4% | Rain |

| Samish River | 11.2% | Rain |

| Willapa River | 11.3% | Rain |

| Nemah River | 12.1% | Rain |

| Naselle River | 17.18% | Rain |

| Dickey River | 22.8% | Rain |

| Snow Creek | 23.6% | Rain |

Source: Demographic Geneflow Model, Hoffman 2014, Marston and Huff 2020.

For example, a study on the Clearwater River, which is one of the few streams that has not received hatchery steelhead releases on the Olympic Peninsula, showed that spawning typically occurs about a month earlier in tributaries when compared to the mainstem Clearwater River (Cederholm 1984). This same study also observed wild steelhead spawning starting in January, far before the Department’s March 15 cutoff date.

Variability in spawn timing among wild and hatchery steelhead, combined with the broad application of the March 15 cutoff date, means that the abundance of wild steelhead may be chronically underestimated in some streams, while masking the decline of wild fish in other streams.

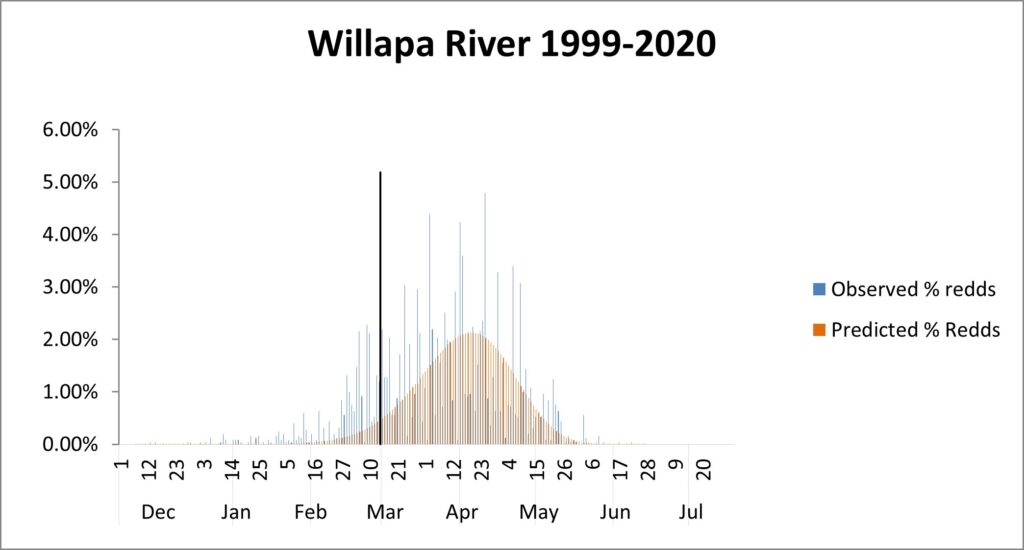

For example, based on spawn timing curve modeling, 10% to 17% of wild steelhead in Willapa Bay are spawning prior to March 15 (Figure 1). During low-abundance years, these documented early spawning fish are assumed to all be hatchery fish. This has real significance for anglers, because the forecasted numbers of returning wild fish determines the difference between an open and closed fishing season.

On the other side of the coin, managers’ adherence to the cutoff date continues to mask the decline of wild populations in many basins. In watersheds where redd counts do not begin until March 15, the loss of early returning, and early spawning, steelhead was likely to go completely undocumented.

Early returning and spawning fish once made up a significant component of western Washington wild steelhead populations. For example, an early hatchery (1907) on the Sauk River, which now has very few fish spawning before March 15, started spawning its wild broodstock in early February (Riseland 1907).

Similarly, McMillan et al. (2021) showed that the peak migration of wild Olympic Peninsula winter steelhead is now 1-2 months later than it was historically and that there used to be a much greater degree of overlap between hatchery and wild fish than there is currently. They pointed to hatchery practices, non-selective harvest, and habitat degradation as drivers of decline for this critical portion of the wild steelhead population.

Another example is in the Chehalis basin, where hatchery fish on the spawning grounds have likely masked the decline of wild steelhead in many parts of the basin. As discussed above, the hatchery releases in the Chehalis basin are from integrated programs, but WDFW has been utilizing the March 15 cutoff date to enumerate wild steelhead returns.

As a result, hatchery fish likely make up a significant number of the steelhead counted each year in abundance estimates. This is particularly true recently, when the rivers have been closed to recreational angling, which is typically one of the primary means of preventing hatchery fish from reaching the spawning grounds.

Modeling done on the Wynoochee River estimated that with the river closed to fishing, hatchery fish would be expected to make up ~68% of the fish on the spawning grounds (Marston and Huff 2022). That means that of the estimated 755 steelhead spawning in the watershed in 2022, only 242 were actually wild fish. The rest were likely hatchery fish that simply managed to survive past March 15.

During the 2024/2025 season, a portion of the Chehalis basin re-opened to fishing through March 1. Managers chose this timeframe to target hatchery fish and minimize impacts on wild fish. However, once again, this management approach is out of alignment with the integrated hatchery program returns because these hatchery fish mostly return during the same times as the wild populations. A shorter season through mid-March at the peak of the run would have been more appropriate to harvest returning hatchery fish.

Next steps and hopeful signs

Perhaps the biggest problem with the March 15 cutoff date is the clumsy one-size-fits-all approach applied for decades across much of western Washington. Using a cutoff date to guide fishery management is not intrinsically bad, but it must be supported by the data and needs be tailored to individual watersheds. In places where there is more overlap with hatchery fish, other monitoring and population estimating approaches, such as expansions based on spawn timing curves or modeling approaches, would be a better approach and should be considered by managers.

Integrated hatchery programs still pose a significant challenge for any cutoff date, and the best path forward is not necessarily clear. In Oregon rivers, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife has attempted to deal with the issue by conducting snorkel surveys to determine hatchery and wild ratios among returning steelhead, but high and turbid water has limited the utility of this approach.

One approach would be full fish-in monitoring. This could be accomplished by linking Sonar and test fishing to get hatchery and wild counts and ratios entering a watershed, then conducting spawning ground surveys and accounting for sources or mortality such as predation and fisheries-related impacts (harvest and catch and release mortality) to account for hatchery and wild escapement. However, such an approach would be costly and would need to be weighed against the value of the hatchery fishery.

The good news is that WDFW is starting to recognize the need to address the limitations of the March 15 cutoff date. While it is still broadly utilized to guide management, there are new monitoring efforts underway in both Willapa Bay and the Lower Columbia River attempting to account for pre-March 15 wild spawners.

However, there is still significant work to be done, especially in the Chehalis River basin, where the March 15 cutoff is completely incompatible with the current hatchery strategies in the basin.

Throughout much of Western Washington, the cutoff date is undoubtedly misinforming fisheries managers about the abundance of wild steelhead. With steelhead in the Lower Columbia and Puget Sound already ESA-listed and a decision on whether to list Olympic Peninsula steelhead pending, addressing the shortcomings of the March 15 cutoff date should be a top priority at WDFW.

Citation

Hoffmann, A. 2017. Estimates of gene flow for select Puget Sound early winter steelhead hatchery programs. Unpublished Report. Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. Olympia, Washington.

Marston, G. and A. Huff. 2022. Modeling hatchery influence: estimates of gene flow and pHOS for Washington State coastal Steelhead hatchery programs. Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. Olympia, Washington.

Cederholm, C. J. 1984. Clearwater River wild steelhead spawning timing. Pages 257–268 in J. M. Walton and D. B. Houston, editors. Proceedings of the Olympic wild fish conference (March 23–25, 1983). Fisheries Technology Program, Peninsula College, Port Angeles, Washington.

Riseland, J.L. 1907. Sixteenth and seventeenth annual reports of the State Fish Commission to the Governor of the State of Washington. 1905–1906. Wash. Dept. Fish and Game, Olympia.