Triumph to tragedy.

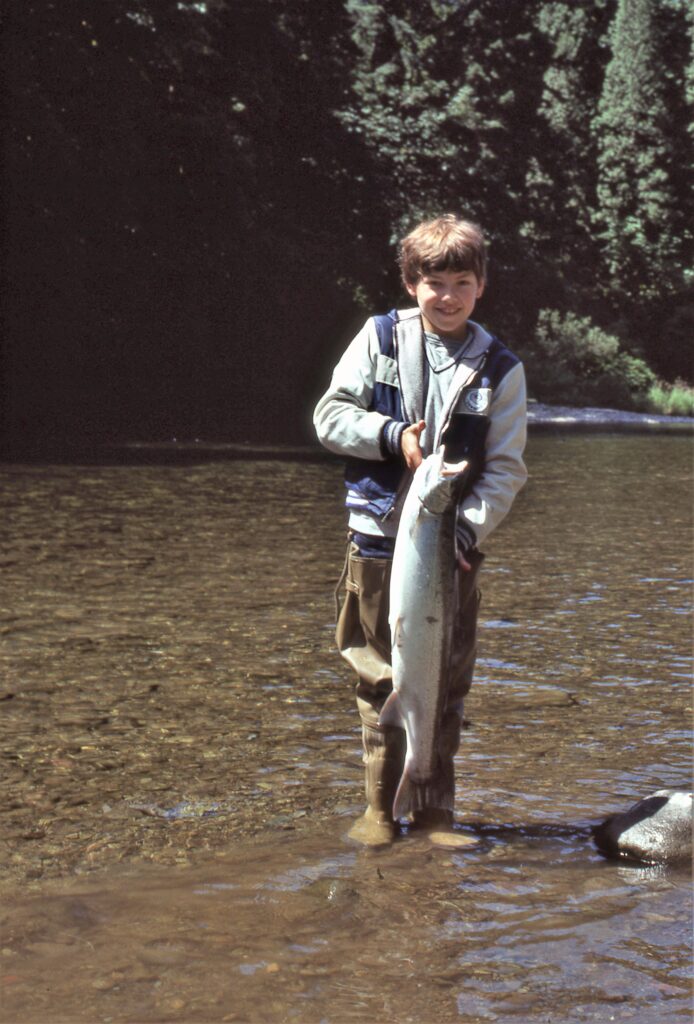

That’s one way to describe my journey as a steelheader. Or perhaps, like Benjamin Button lived, old to young.

It’s had a strong effect on my outlook as both an angler and a scientist.

Yet, my steelhead sojourn also has offered me opportunities that I would not otherwise have indulged in. The lessons from those experiences are the reason I’m taking a different approach to my fishing this year.

I reached my teenage years during the mid- to late-1980s, not long after the Miracle on Ice, when music was awesome, and ocean survival was unusually high (relative to historic averages) for steelhead.

Each summer morning, I walked 10 yards to the river behind our house and fished my way downstream one mile. I then walked back to the house, grabbed my bike, and rode several miles upstream before fishing my way back downstream. I typically didn’t make it home until after dark. Those were long, glorious days.

There was nothing like summer steelhead combined with AC/DC and Blue Oyster Cult.

Image: Bill McMillan

Alas, it all turned to ashes in the 1990s. Ocean survival plummeted, climate change effects began to intensify, grunge and Cobain took over, and bounty turned to scarcity.

For some strange reason the pattern followed me to the Olympic Peninsula (OP). In 1998, my first winter living in Forks, the Quillayute watershed returned 18,896 wild winter steelhead. I was shocked by the number of steelhead I saw snorkeling and fishing.

The next year was even more remarkable, with a run size of 21,021 wild winter steelhead. One day while snorkeling that year I counted almost 100 adult steelhead in a single large pool that was approximately 400m long. Half of them were stacked under a huge boulder, hiding during a period of low flows.

Image: John McMillan

I fished every day I possibly could, arriving home in the dark, just as I did as a boy on the Washougal River. I was too excited and full of wonder to do anything other than snorkel, fish, or watch fish.

While landing a steelhead one day, a guide rowed over and asked if I needed help. I declined. He and his client watched me land the fish – it seemed a novelty to them. We then chatted for several minutes, mostly about steelhead. As they departed, the guide turned and said, “When my grandfather moved to Forks, he said there was a fish behind every rock and an elk behind every tree.”

I nodded. What better did I know?

I felt as though I had gotten a do-over. Fated to live in proximity to another great steelhead river, with others close by. No fear of imminent collapse of the fishery.

Alas, I counted my chickens before they hatched.

Run sizes of wild steelhead in the Quillayute have declined by more than half those numbers, to a mere ~8,000-9,000 steelhead over the past two years.

And statistically, winter steelhead populations in the Queets, Hoh, and Quinault Rivers are in long-term decline since the start of the modern period of record in 1980.

As Michael Scott, of the television show The Office fame quipped, “Well, well, well, how the turntables….”

After seven years of education and 25 years’ experience as a fishery scientist, however, I’ve come to appreciate that variability is just part and parcel of being a steelheader, or an angler of any salmonid.

Conditions change. Fish change. There is a natural ebb and flow in their productivity.

Still, as we outlined in our last post, this time is different. Scientifically speaking, there is a high level of overall uncertainty moving forward. Extremes have become more extreme. The world is warming. Our rivers and oceans are changing.

Image: John McMillan

Now, I see that I need to change, again. The first decade I lived in Forks I fished an average of 100 days out of the 120-day season from January through April. I didn’t fish all day every day, but like my time on the Washougal as a teenager, I sought to maximize time on the water. The fish were abundant. There were, comparatively, few guides and far fewer visiting anglers.

Since moving back to the OP after graduate school, I’ve slowly reduced my angling, replacing it with snorkeling, photography, and redd counts. Not because I want to. Rather, because I can see the fish are struggling. And when they are struggling, my angling enjoyment is diminished.

I will fish for steelhead this season, though almost solely in the Quillayute system because it has the largest margin for error and the most restrictive emergency regulations in place that allow angling. But also because I have a strong emotional and spiritual attachment to living as a fisher-gatherer. It is all I have known in my life. Rivers and steelhead have been and will always be my anchor to this earth.

Nonetheless, I’m cutting back my angling time this year more than last year, just as I did in the 90s. To live within my means, I’ve set a personal limit for encounters on wild steelhead and to maintain my wading, casting, and mending skills, I’ll spend much more time fishing a hook-less fly.

Snorkeling and photography will also help fill the void.

Nonetheless, my decision to reduce my angling is unlikely to have any impact on the overall fish populations. Setting aside my rod entirely would be virtuous, but that doesn’t seem to get us far in this day and age. If anything, it’s fodder for antagonism in our community of fisher-folk.

And that is why a series of poor run sizes, though painful, are also important. They invoke emotion and raise difficult, but necessary, points of discussion. For me personally, they also offer a unique opportunity. Time on the river creates chances to practice new techniques and hone skills that are otherwise given short shrift when run sizes are larger and catching is better.

Image: Bill McMillan

For example, I first taught myself to spey cast with a single-handed rod in the early-1980s as a boy, but it wasn’t until fish runs declined from late-1980s through the early-1990s that I really spent time perfecting the technique. I had given up hope of consistent catching and instead of ruminating, I eventually shifted my focus to casting and mending. Over the next few years, I fought through trial and error regarding rod length, line, fly size, and timing and hand placement, until eventually I was able to consistently achieve the types of casts and presentations I had been searching for.

Little did I know that several years later my decision to focus on skills rather than catching would pay big dividends in my new home on the OP. The rivers were larger and stronger than my previous home waters, and there were many places that required a longer cast than I was accustomed to.

My epiphany occurred in February of 1998. I saw two steelhead holding on the far bank behind two boulders. Both were male. One about 10lbs, the other larger, perhaps in the high teens. There was no room to back-cast. No room to wade more than a couple feet from the bank. The only way to reach the fish was with – though I didn’t know the name of the cast at the time – a “perry poke.” After a few attempts, I eventually reached the other side and within four casts had hooked and lost the larger steelhead.

Shaking with excitement, I failed to notice the Game Warden who had been observing me. He said, “What kind of cast is that? I’ve never seen anyone do that.”

Image: John McMillan

I immediately realized the serendipity of my practice-casting from years earlier and came to value the creativity fostered by the poor returns of steelhead. Necessity is the mother of invention.

And that is my theme for this winter. Improving my skills as an angler and taking the time to hone and fine-tune tactics I would normally eschew as a waste of time when the fishing is good.

It isn’t the ideal situation. I would rather fish with clear eyes and a full heart knowing the runs are in great shape.

But in down years for the iconic sport fish of the Pacific Northwest, as this year is thus far, it’s the way I make the best of a bad situation.

Over the next few weeks, we’ll be sharing more about what it means to be a steelheader under these regulations with some guest perspectives from those in the sportfishing industry.