Shauna Stephenson

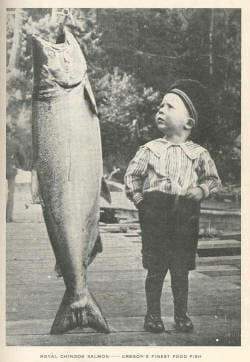

We’ve all heard stories from our grandparents of unbelievable abundance and sizes in their fishing forays — the salmon so numerous it boggled the mind, and those Lahontan cutthroat trout so big you couldn’t wrap your arms around them. Yet even with these anecdotes it’s still hard to internalize just how different our experience of today is from way back when. That’s just human nature: memory is hard to maintain, especially across generations.

The problem is, our short-term memory has real consequences for conservation as we continually reduce our expectations and drop the bar far too low. Because every new generation has no direct experience with the relative abundance of the past, and because we are perhaps too quick to discount grandpa’s stories of “when I was a kid,” we accept a new (almost always diminished, when it comes to the natural world) standard of “normal.”

Given its importance to conservation, the concept even has a formal name: Shifting Baseline Syndrome (SBS). The field of fisheries is, actually, what prompted the use of the term in ecology and conservation; it was first penned in 1995 in a one-page seminal paper by Daniel Pauly assessing the dire situation of our ocean fisheries. Pauly noted that each incoming manager or scientist assesses a fishery at the beginning of their career, and then measures change against that standard. With the continued declines in biodiversity and abundance, the perception of normal is lowered with each generation.

The consequences of SBS (also aptly called “environmental generational amnesia” and “a loss of Faith in Nature1”) are real: tolerance of decline, acceptance of the causes of degradation, and inappropriately low targets for conservation, restoration or management. One enterprising grad student in Florida was incredibly creative in measuring our tolerance of the diminished: she used archived photos, from those fishing charter docks where saltwater guides take pictures of clients’ catches, to measure remarkable declines (over 80 percent) in the size of the landed fish from 1956 to 2007 (and she was smart to note that the fees these folks paid did not go down despite their eroded experience; see photos in this NPR story on her work). Other recent studies confirm that, compared to older fishermen, younger fishermen are far less likely to characterize fishing sites as depleted or species/stocks as declining in number or size.

This concept of the shifting baseline syndrome has increasing relevance for recovery of our Snake River salmon and steelhead runs. Following a steady decline since the 1950s as the last four dams were installed on the lower Snake River, returns of Snake River salmon and steelhead have been dismal for several decades. They are on the path to extinction.

Importantly, salmon returns are often assessed by managers not in comparison to historical runs but based on recent 10-year averages, meaning the bar is continually lowered. As a result, even modest increases in salmon returns are incorrectly interpreted as “the best run in years” despite being far, far below historical abundance.

Clearly, our baseline has shifted.

This shifting baseline was recently quantified in a study in one of the most special places and intact habitats remaining, Idaho’s Middle Fork Salmon River in the Snake River Basin. In a detailed reconstruction, the authors integrated archival redd counts with modern counts and other data to estimate the recent historical (1950s-60s) production potential of spring/summer chinook salmon in the Middle Fork — that is, they estimated how many salmon the system produced before the hydro-system was completed and before the fish had to pass eight dams to and from the ocean. The MFSR lies mostly in wilderness and habitat in the basin is diverse, connected and in good to excellent condition today. In other words, it is extremely healthy habitat.

The results of the study suggest that — in this prime habitat — current runs average just 3 percent of the mid-20th Century Middle Fork runs, which themselves may have been only 30 percent of runs in the late 1800s. Yet the “viability goal” set by the federal government for the Middle Fork is just 10 percent of this estimated production potential.

The authors of this recent study emphasize how understanding the historic capacity of the Middle Fork, which was arguably in worse condition than it is today (as a result of land management changes), is essential information for grounding our goals closer to what should be. This is a critical point because inevitably we end up managing to meet goals: if the goals are too low, we may not take the actions necessary to achieve actual fish population potential.

We all suffer when we fall prey to the Shifting Baseline Syndrome. As Michelangelo famously stated, “The greatest danger lies not in setting our aim too high and falling short, but in setting our aim too low and achieving our mark.”

We must decide if we want our children’s expectations for salmon to be less than ours, or more like those our grandparents experienced.

Helen Neville is the senior scientist at Trout Unlimited. She is based out of Boise.

1 Lichatowich, J., and R. Williams. “Faith in nature: The missing element in salmon management and mitigation programs.” The Osprey (2015).