Image: John McMillan/The Conservation Angler

Our science advisor looks at the lessons learned from a recent report on intensively monitored watersheds

Quality monitoring and evaluation is a critical component of managing salmon and steelhead populations. The data from this work usually focuses on population trends and can provide managers with information about what approaches are succeeding and what changes could be made to recover salmon and steelhead populations to healthy and harvestable levels.

For example, managers should want to know restoration activities are actually meeting their goals of improving watershed process, habitat conditions, and salmon and steelhead productivity and abundance.

With many salmon and steelhead populations continuing to decline, it has never been more important for managers to have access to quality monitoring and evaluation data. Without it, they are essentially flying blind.

But having access to data is not enough. To recover steelhead and salmon populations, managers must be willing to learn from it and incorporate those lessons into their management strategies.

Intensively Monitored Watersheds

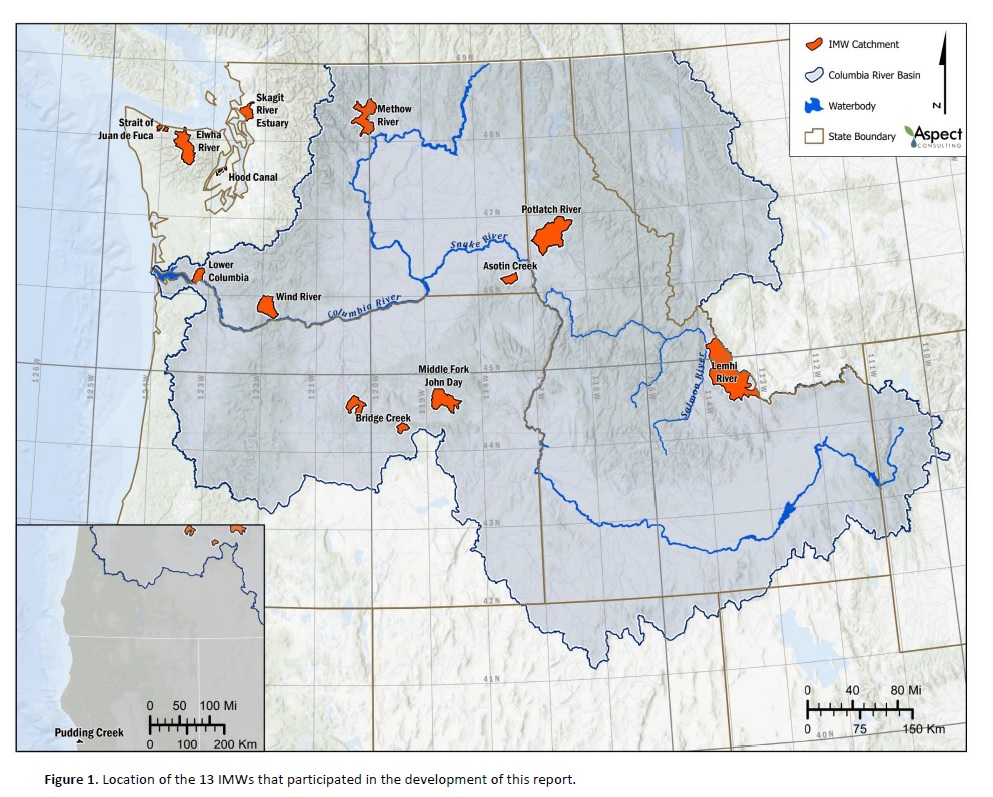

This is where the Intensively Monitored Watersheds (IMW) program comes in. Established in the early 2000s, the IMW program is a comprehensive approach intended to establish a long-term monitoring program to evaluate watershed-scale fish and habitat responses to restoration activities. The program now encompasses fourteen watersheds across the Pacific Northwest.

With over two decades of monitoring data currently collected, the IMW’s now provide critical information on what is and is not working for salmon and steelhead populations in these watersheds.

In 2022, a team of fisheries biologists led by Robert Bilby published a report focused on the management implications from the thirteen Pacific Northwest IMWs. The results of their analysis should be front and center in the mind of every fisheries manager, conservationist, and angler throughout the region.

Habitat Restoration is yielding results (kind of….)

The first key message from the IMW report is that overall habitat restoration is yielding positive responses. With 75% of the watersheds showing positive improvements in habitat function, quality and availability and 53% of projects yielding a positive response by fish in terms of distribution, productivity, abundance and life history diversity.

The greatest benefits are associated with the removal of fish passage barriers (dams and culverts), which consistently and unsurprisingly yielded positive responses by reconnecting fish to historical spawning and rearing habitat. Additionally, improving access to floodplain or estuarine habitat by removing barriers or encouraging beaver colonization increased the growth and abundance of juvenile salmon and steelhead in most IMWs where these restoration activities were evaluated. The results from large woody debris placements were less clear with some IMWs showing a benefit to fish numbers and others yet to yield a response. This mixed result isn’t particularly surprising given how dynamic flow and channel movement often limits the longevity and effectiveness of woody debris additions.

But this is where the catch comes in: While many IMWs reported a beneficial fish response from restoration activities, these responses were largely reserved for the juvenile and smolt life stages, both of which showed increases in abundance, distribution and life history diversity. However, this positive trend did not carry over to adult fish populations in most of the IMWs. Only two, the Elwha River and Wind River, reported an increase in adult fish abundance.

The authors note that “poor marine survival and factors impacting fish outside the area where habitat treatments were applied, such as harvest, hydropower, and hatchery programs, all could limit the capacity of adult fish to respond to improvements in freshwater and estuarine habitat conditions” and that one or more of these external factors affected fish at every IMW.

The key takeaway is that habitat improvements are increasing the numbers of juvenile salmon and steelhead, but to take advantage of this fact, and see improved returns of adult fish, changes to fisheries management that accounts for the impacts of external threats to fish are essential.

The importance of integrated all-H management

“All-H management” is a term commonly thrown around in fisheries circles. It refers to managing across all the limiting factors impacting salmon and steelhead (Habitat, Harvest, Hatcheries and Hydropower) to ensure that recovery actions are sequenced, comprehensive and effective.

Unfortunately, management is rarely done in the comprehensive and integrated manner it is intended. Instead, the limiting factors are dealt with (or not) in individual management silos and the full benefits of the “all-H” approach are not achieved. This is the exact reason why the Pacific Northwest IMW’s are seeing such little improvement in adult abundance, despite habitat restoration and reconnection producing more young fish.

To rebuild and maintain healthy salmon and steelhead populations, managers must consider all the limiting factors and build a comprehensive restoration approach that prioritizes and sequences recovery actions across the threat categories in an integrated manner. For example, this means that if habitat is improved, thus expanding the productivity and capacity of the freshwater environment, fisheries should be altered to allow more adult salmon and steelhead to return to the spawning grounds to fully seed the newly improved habitat.

Instead, far too often, a status quo management regime guides fisheries and runs are fished down to the same levels year after year. A glaring example of this is the steelhead fisheries on the Washington coast, where managers have been operating from the same escapement goals for nearly 40 years with no changes to account for shifts in habitat capacity over that time.

Hatchery impacts are a bit more complicated. Rigorously managed conservation hatchery programs can provide a recovery benefit by helping to reseed the available habitat, but poorly operated hatcheries have a negative impact on wild populations by reducing their productivity and thus reducing the benefits of habitat restoration.

Learning from the Elwha and Wind Rivers

When we look at the two intensively managed watersheds where adult fish abundance did increase, the Elwha and Wind Rivers, we see that both have included significant all-H integration approaches.

On the Elwha, the comanagers have strategically utilized hatcheries for conservation purposes, while also closing the freshwater fishery to help fish populations recolonize reconnected upstream habitat following dam removal. This conservative integrated management approach designed to allow the habitat and fish to recover post dam removal is bearing fruit across multiple populations of salmon and steelhead. This fall, the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe was able to hold a ceremonial and subsistence fishery because of consistently improving adult Coho returns.

Image: Thomas O’Keefe, American Whitewater

The response in the Wind River has been less dramatic than the Elwha, but the watershed has also benefited from all-H actions. For example, WDFW eliminated hatchery steelhead releases and designated the Wind River as a Wild Steelhead Gene bank, and the steelhead fishery is now managed strictly for catch and release of wild fish.

The key recovery action was the removal of Hemlock Dam on Trout Creek, a productive Wind River tributary. The dam had a defunct fish ladder and acted as a partial barrier for summer steelhead. After its removal, the steelhead population upstream showed a marked increase in returning adults and the number of redds compared with the rest of the watershed. However, the report’s authors note that there are still significant limiting factors for Wind River steelhead in the mainstem Columbia River where many juveniles rear, including predation and habitat degradation that need to be incorporated into recovery planning.

Building on the Lessons of Intensively Monitored Watersheds

If there is one key takeaway from this report, it is the reminder that it is time for managers to stop treating the factors limiting salmon and steelhead recovery as independent elements to be addressed separately. Impacts from fisheries, hatcheries, and habitat degradation are compounding and intertwined. Effective management must be as well. Managers must consider the ecosystem as a whole and management actions must be sequenced and integrated across all the threat categories to achieve real benefit.

When taken to heart, the IMWs clearly show that where all-H approaches are being done, we are seeing improvements in salmon and steelhead populations. Where it isn’t, we continue to see populations struggle and fail to take advantage of investments in habitat restoration and reconnection. While the report shows that habitat restoration alone is unlikely to achieve recovery across the region, it also provides a hopeful message by illuminating that integrated all-H management provides a pathway to rebuilding salmon and steelhead populations across the region.