This Science Friday we have Part 2 of a three-part series on steelhead in the Great Lakes (catch up on Part 1 here, which covers early history of Great Lakes steelhead). Last time, Brian Morrison described the early history of steelhead and rainbow trout, including their initial introductions and the onset of fisheries that soon followed.

Today is another guest piece, this time by Brian Morrison, Fred Dobbs, and Chris Atkinson. This article was originally published in The Osprey in September 2010 (link to the original article in The Osprey is here: http://ospreysteelhead.org/archives/TheOspreyIssue67.pdf).

The Osprey has a history of providing scientific information and conservation perspectives on salmon, steelhead, trout, char and their habitats across the Pacific Northwest and throughout North America. We at TU support The Osprey and if you are interested in donating to help maintain the publication, which relies on donations from anglers, please hit the link and show your support: http://www.theconservationangler.org/osprey.html.

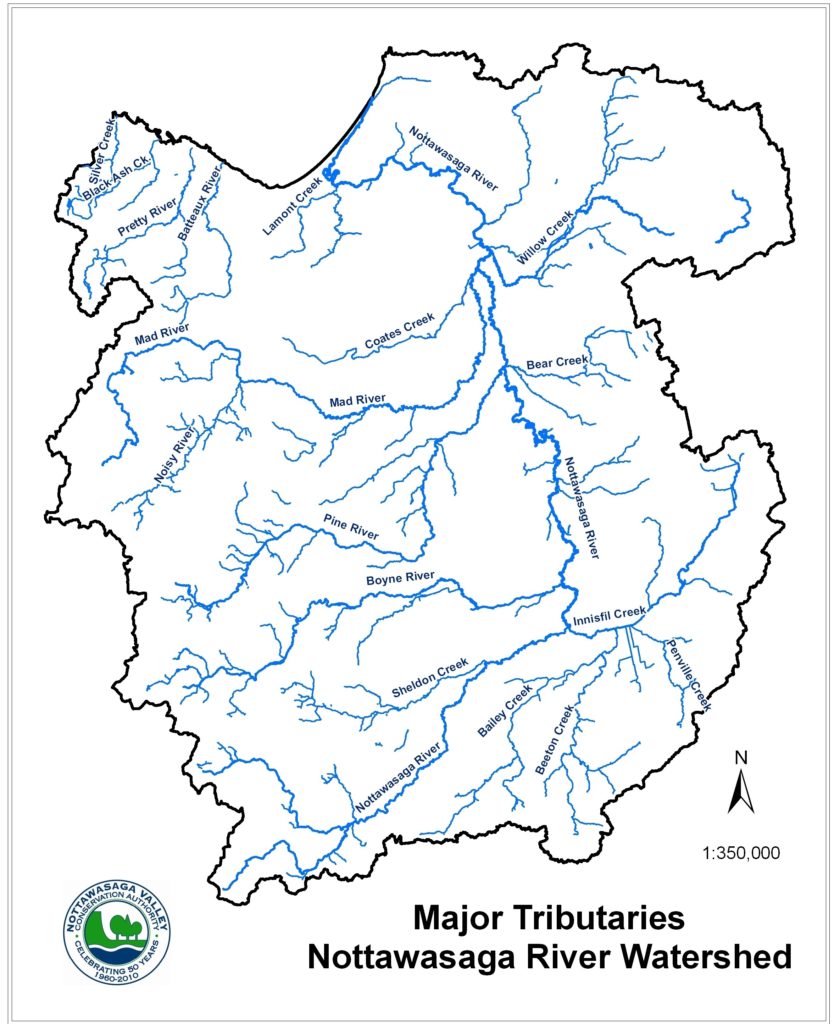

The authors focus on a tributary to Lake Huron, the Nottawasaga River, which is located in central Ontario, Canada. Without further ado, here is the first piece on the history of the Nottawasaga River and its populations of steelhead and salmon.

———————

Migratory rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), also known as steelhead, were introduced into Lake Huron in 1876 when the AuSable River in Michigan was stocked with rainbow trout from the Northville Hatchery, MI. Steelhead were accidentally released into the Pine River, a Nottawasaga River tributary by 1900, likely offspring of fish spawned from the McLeod River, California. As early as 1903 adult steelhead were documented in tributaries of the Nottawasaga River, and it has been suggested as one of the first documented occurrence of wild adult steelhead in the Canadian waters of the Great Lakes proper. Shortly thereafter, steelhead were making seasonal migrations between the Nottawasaga River and Georgian Bay/Lake Huron; with these fish likely resulting from the accidental release of steelhead into the Pine River.

The life history characteristics of the naturalized steelhead populations in the Great Lakes resemble those of anadromous forms native to Pacific coastal drainages, although local populations display varying life history traits. Spawning takes place in the spring, though mature fish may enter their home tributary as early as August of the previous year. Mature fish migrating in the summer/fall will generally travel greater distances than their spring cohorts. They are usually first to spawn in the winter/spring and appear necessary to maximize recruitment in headwater areas.

However, fall migrants are thought to have an advantage over spring migrants due to warmer water temperatures and more stable discharge regimes, which allow for a greater opportunity to navigate obstacles such as rapids, waterfalls, and dams/fishways. The life history strategy of fall migration may have developed from summer run steelhead transplanted from their native range. Spring migrations, which are a continuum from fall migrants, generally begin in March through to June. Spawning activity generally commences in February through June, but spawning may begin as early as December.

All wild Great Lakes steelhead populations, including Lake Huron/Georgian Bay Rainbow Trout have the ability to spawn multiple times, a characteristic that appears to be a prerequisite for optimal recruitment. Most healthy populations have repeat spawning levels between 50 and 70 percent for both sexes. Males tend to have higher natural mortality and therefore lower repeat spawning, probably due to multiple spawning events (within one season) and the protracted period of time spent in spawning streams. Males are capable of spawning three or four times in successive years while females commonly have four to six spawning migrations in healthy populations, a trait also exhibited in healthy steelhead populations in Kamchatka, Alaska, and introduced populations in Argentina (e.g., Rio Santa Cruz).

The Nottawasaga River drains an area of 3,000 km2, with a mainstem length of 120 km. It flows north draining into Nottawasaga Bay, Georgian Bay. There are three major headwater areas originating in the Niagara Escarpment, Oak Ridge Moraine and the Oro Moraine. Steelhead naturally reproduce in many Nottawasaga River tributaries including the Pine River, Upper Nottawasaga River, Boyne River, Mad River, Noisy River, Sheldon Creek and several other smaller streams due to a lack of dams and other barriers. Steelhead in the Nottawasaga River can access hundreds of kilometers of prime spawning and nursery stream habitat, more than in any other watershed in the Province of Ontario.

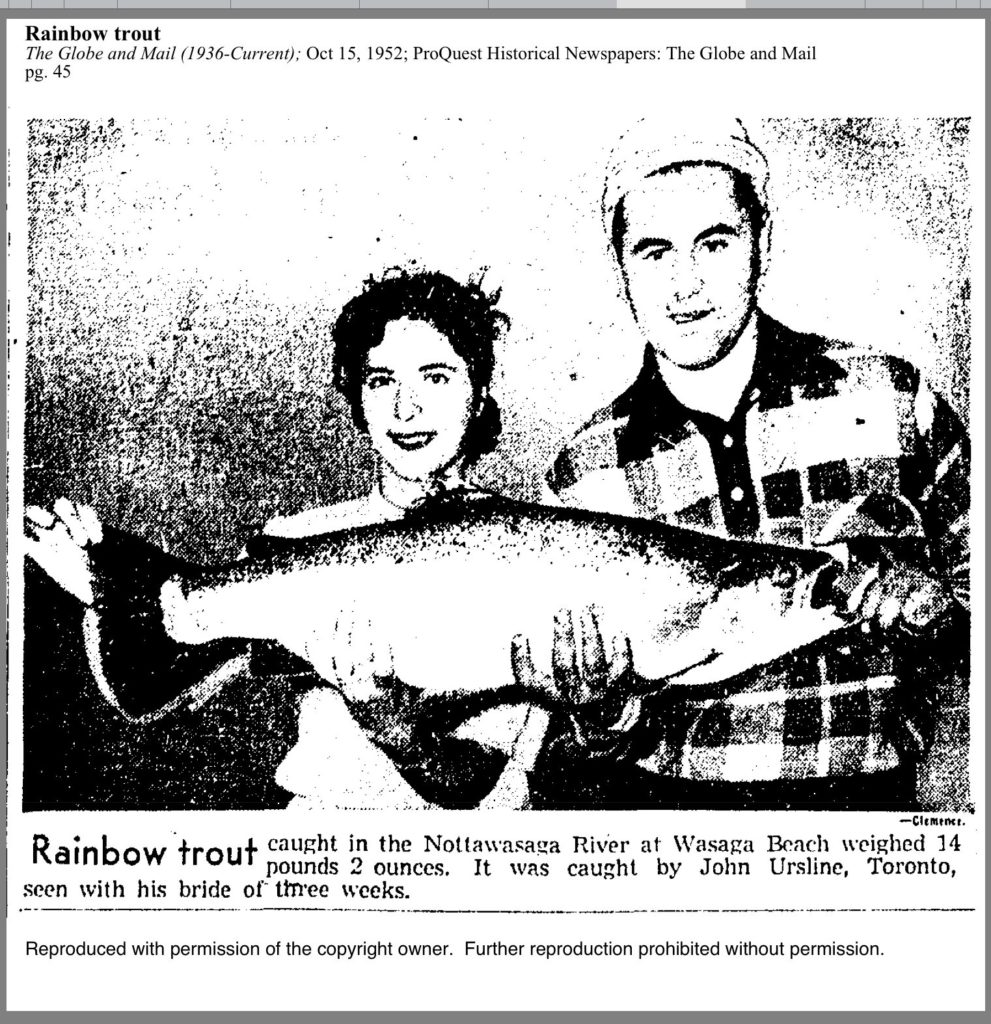

The Boyne River is the fifth largest tributary within the Nottawasaga River watershed, draining 230 km2. The Boyne River originates on top of the Niagara Escarpment and has a mainstem length of 45 km. The Earl Rowe Fishway, where most of the adult population data is obtained, is about 7 km upstream from the confluence with the Nottawasaga River and is about 80 km from Georgian Bay. The majority of the Boyne River subwatershed is above the Earl Rowe Fishway (210 km2). It is believed that the Boyne River is one of the better producers of Rainbow Trout alongside the upper Nottawasaga River and the Pine River. The Boyne River is the only Niagara Escarpment tributary within the Nottawasaga River that allows access to the extreme headwaters above any natural barriers. Fishways are present on the Boyne River (Earl Rowe Fishway) and the upper Nottawasaga River (Nicolston Fishway), which provides the only estimates of population size and adult life history characteristics. The Nottawasaga River has been known as a big fish river, where the average size of fish handled in fishways has been greater (average size at age is 15% larger) than any other Lake Huron/Georgian Bay population. The past Ontario record was captured out of the Nottawasaga River, weighing 29.13 lbs (13.2 kg). Introduced in the 1960s, the Nottawasaga River also contains one of the largest naturalized Chinook Salmon populations in the Great Lakes, which is thought to currently support the sport fishery within Georgian Bay and part of Lake Huron. In addition, the Nottawasaga River contains one of the earliest running populations (July) of Chinook Salmon as well as spring run and spring spawning (April) in the Boyne River, but spring spawning success is unknown.

—————

Think about that, a 29lb steelhead from the Great Lakes!

Next post Brian and the other authors dive into the development of different life histories and genetic structure of steelhead in the Nottawasaga River.

This continues to highlight how rapidly steelhead can diversify if they are afforded sufficiently suitable habitat, which is just one reason that we at TU and WSI continually focus on protecting high quality habitat — in both the Northwest and the Great Lakes.

Have a safe and happy weekend everyone.