This Science Friday we have the final part of a three-part series on steelhead in the Great Lakes.

This is the second-half of last month’s article, authored by Brian Morrison, Fred Dobbs, and Chris Atkinson. The article was originally published in The Osprey in September 2010 (link to the original article in The Osprey is here: http://ospreysteelhead.org/archives/TheOspreyIssue67.pdf). The Osprey has a history of providing scientific information and conservation perspectives on salmon, steelhead, trout, char and their habitats across the Pacific Northwest and throughout North America. We at TU support The Osprey and you are interested in donating to help maintain the publication, which relies on donations from anglers, please go to this link: http://www.theconservationangler.org/osprey.html.

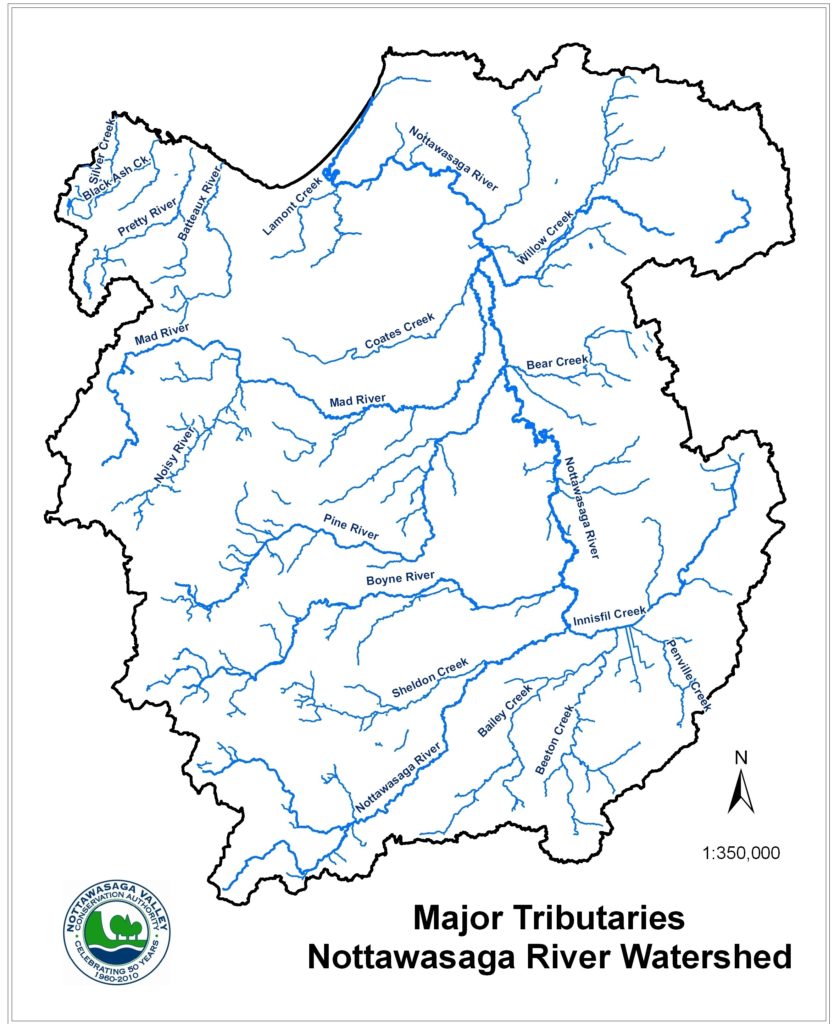

This week the authors focus on a tributary to Lake Huron, the Nottawasaga River, which is located in central Ontario, Canada. Without further ado, here is the first piece on the history of the Nottawasaga River and its populations of steelhead and salmon.

———————

The Nottawasaga River did not support a popular sport fishery for steelhead until the 1940s. It is believed that early maturing adults dominated the spawning populations from the 1940s until the early 1960s. Fishway construction starting in the1960s allowed access to previously inaccessible habitat. During the late 1960s, a large steelhead sport fishery was established. During this time, the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (OMNR) opened up seasons to increase opportunities for anglers to fish and harvest steelhead year-round. In 1987, the OMNR created a year round open season from the mouth of the Boyne River to Georgian Bay (70kms of angling access) on the Nottawasaga River, allowing a daily possession of five steelhead. Angling effort increased proportionally as longer seasons and increased harvest opportunities were created. It was believed that a large proportion of the Boyne River and upper Nottawasaga population over wintered in deep pools on the mainstem Nottawasaga below the mouth of the Boyne River, and became vulnerable to harvest after this new regulation. By the early 1990s, a decline was observed in upper Nottawasaga and Boyne River populations and decline in repeat spawning rate (Figures 2, 3 and 4). In 2008, a catch and release only zone for steelhead was established, through the work of the Nottawasaga Steelheaders organization, from the mouth of the Boyne River to the Pine River to protect overwintering Boyne River and upper Nottawasaga populations. Unfortunately, a lack of monitoring has not been able to provide data on whether the new regulation is achieving the desired recovery in population size, and proportion of repeat spawners.

A study of the genetic stock structure of wild Nottawasaga steelhead was undertaken to determine the genetic diversity within the Nottawasaga River and neighboring watersheds. A total of 121 juvenile steelhead were collected from 6 Nottawasaga River tributaries. A total of 18 different strains (genotypes) were identified. This is the highest documented number of steelhead strains found in any river system on the Ontario side of the Great Lakes. Four of the strains were newly identified as being specific to only the Nottawasaga River and neighboring Bighead River steelhead populations. Of special interest was the fact that the entire Nottawasaga River was genetically different when compared to those steelhead populations from other tributary systems in the Province of Ontario. Within the Nottawasaga River, local population structure was evident. For example, the Pine River steelhead population was genetically different from the Sheldon Creek, which was different than the upper Nottawasaga River. This means that strains of steelhead present in one tributary system are different than those of another neighboring tributary system. The upper Nottawasaga River steelhead showed the highest genetic variability and is the greatest recorded in the Great Lakes basin when compared to other naturalized or hatchery populations (e.g. Ganaraska River, ON; Salmon River, NY). Fishway data indicate that hatchery origin (clipped) steelhead have never comprised a significant proportion of the total population (<1%) at both Earl Rowe and Nicholson Fishways across all years of monitoring, and supported through anecdotal angling evidence.

The typical age of smolting in major spawning tributaries (e.g. Boyne River) is age-2. This differs from the upper Nottawasaga drainage, which has a high proportion of stream age-3 smolts. Most smolts leave the river during late April and May, but some begin the smolting process earlier, and move downstream in September and October. Nottawasaga steelhead typically spend one to three years in Georgian Bay prior to their first spawning migration, with three years being dominant. Males are known to mature earlier than females, often maturing after only one year in the lake. The Nottawasaga drainage is known to contain a unique life history of rainbow trout known as the ‘half-pounder’, which has been described in northern California, southern Oregon, and Kamchatka tributaries. Half-pounders typically spend only 2-4 months in the estuary or nearshore lake environment, enter the river on a foraging foray and often overwinter within the river environment before returning to the lake the following spring. The precocious males are usually larger than fish with the half-pounder life history, where approximately 42cm (16.5 in) is the threshold between the two. Based on evidence from other Great Lakes wild steelhead populations, approximately 33% of the population exhibits a half-pounder life history trait. These fish will then rear in the lake for 1-2 years before returning to spawn. This behavioral strategy makes these individuals susceptible to angling mortality within the river and near-shore lake environment before they become sexually mature.

Repeat spawning rates have ranged from a high of 58% repeat spawners to a low of 23%, with an average of 43%. A minimum of 55% is considered necessary to maintain a healthy population with the assumption that there is approximately 30% natural mortality and 15% angler mortality. Repeat spawning rates have declined with population size following increased angling pressure and longer open seasons for anglers. An exception occurred in 2005, where a large year class inflated the proportion of repeat spawners, with the population having very few multiple (greater than two spawning events) repeat spawning individuals (Figure 4).

The wild steelhead inhabiting the Nottawasaga have had approximately 110 years of natural selection to develop genetic and life history diversity, maximize local abundance and productivity and behaviors to optimize population size based on the local environmental templates (e.g. hydrology, geomorphologic characteristics). The creation of local life history and behavioral traits and co-adapted gene complexes (genetic structure) has been developed by allowing volitional access to high quality habitat throughout the watershed, not stocking, controlling harvest, and letting the fish do what they wish. This has been seen in other wild steelhead populations within the Great Lakes (cf. Superior Steelhead, The Osprey No. 39). The naturalized steelhead in the Nottawasaga River provide hope for restoring wild steelhead to parts of their historic range where loss of access, habitat, and over harvest have plagued wild steelhead. This case study highlights that local adaptation and population recovery is possible when wild fish are given a chance to recover.

—————–

We hope you enjoyed the article and thank the authors and The Osprey for sharing their work with us.

Have a wonderful weekend everyone, stay safe and be healthy.