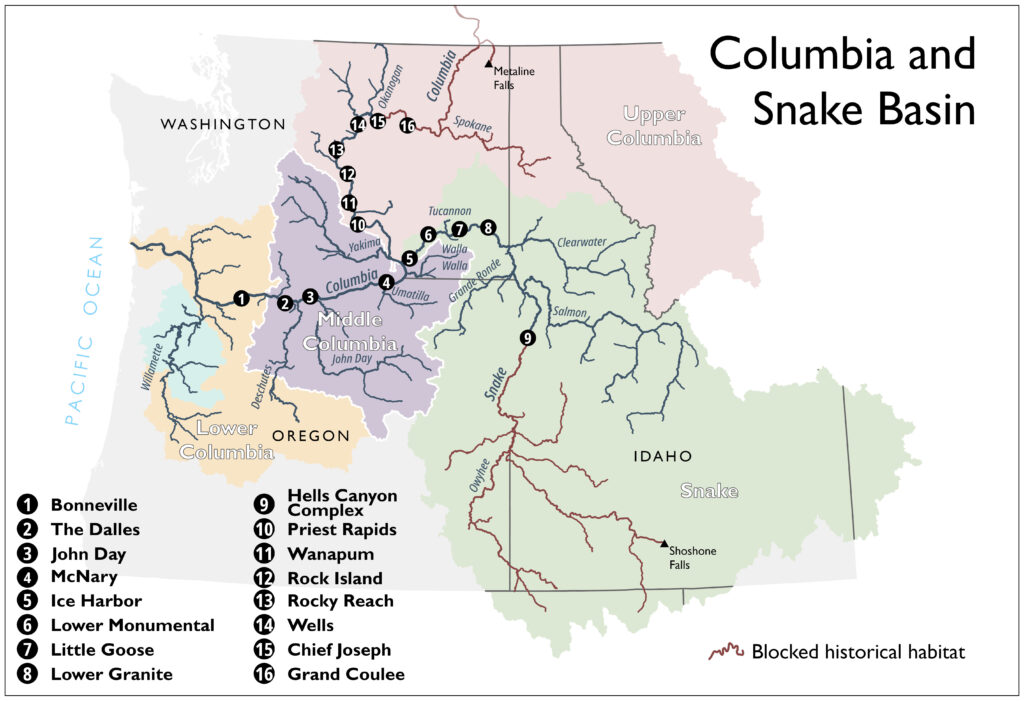

In Part Two of our Science Friday article on overshoot summer steelhead in the Columbia River basin, we look at the impacts to fish traveling downstream through the hydro system, and management changes to help improve steelhead survival.

Last week, in the first part of our article on overshoot steelhead in the Columbia Basin, Gary Marston looked at recent research on summer steelhead who swim past their spawning streams, passing dams multiple times and increasing their mortality and straying rates, trying to find coldwater refuge. This week, in the second part, we look at the hydro system’s impacts on adult steelhead migrating downstream.

So what about fish traveling back downstream?

Adult steelhead falling back to their natal waters display bimodal migration timing, meaning that there are two peaks when the majority of fish move through the system. One is in the fall, (starting in late September) and another occurs in late winter (March). Unfortunately, these two periods of downstream movement usually correspond with low flows and challenging conditions for adult fish moving downstream through the hydro system.

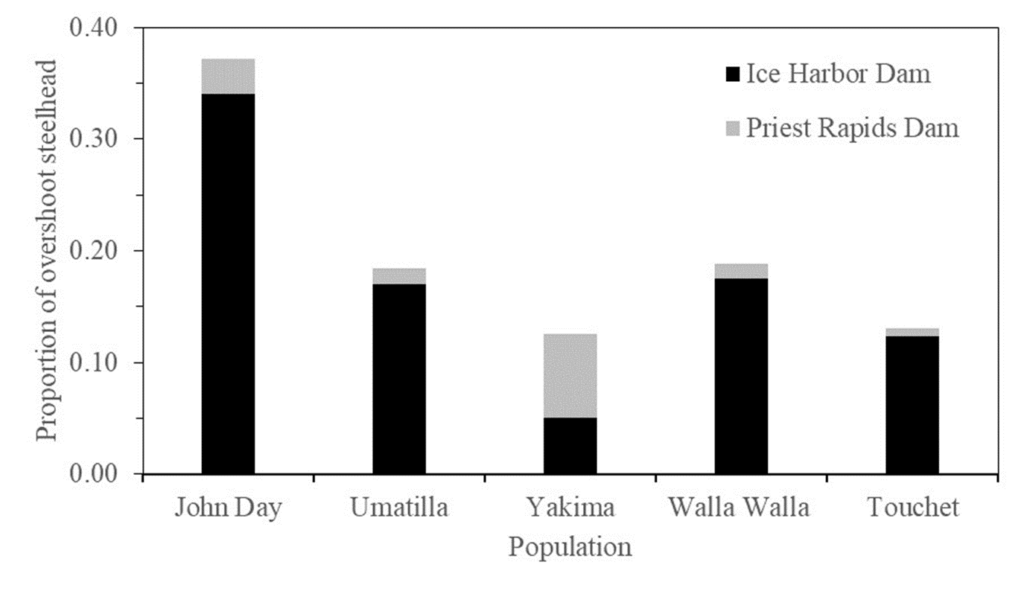

The Murdoch et al. 2022 study found that between 2010 and 2017 only 59% of overshoot steelhead successfully migrated back downstream of Priest Rapids Dam. More troubling was that only 22% of overshoot steelhead detected at Wells Dam successfully made it back downstream of Priest Rapids Dam. In 2015 only 32% of overshoot fish in the Snake River successfully fell back downstream. Hatchery fish were also less likely to successfully fallback downstream than wild fish in three out of the four populations assessed by Richins and Skalski.

Image: Matt Mayfield.

So, what happened to the steelhead that did not make it back to their natal waters? Sport fisheries were only a minor source of mortality for wild fish. Those impacts were found to be less than 1%. Straying was not a major issue in the upper Columbia, but it was in the Snake River.

Based on the results of the Murdoch et al. study, overshoot wild steelhead in the upper Columbia River had a low straying rate with only 3.2% of fish detected dipping into non-natal tributaries and only five tagged fish were detected in those tributaries during the spawning period. Straying rates were much worse in the Snake River. Among the mid-Columbia overshoot steelhead who had been tracked to the Snake Basin and never returned to their natal streams downriver, approximately 40% were last detected on the spawning grounds in the Snake River basin.

It is also important to note that this straying rate should be considered a minimum estimate as several major tributaries, including the lower Grande Ronde and lower Salmon River, lack PIT tag detectors.

Image: Eric Crawford

A particularly troubling result from the Richins and Skalski study was the exceptionally high straying rate for Tucannon River wild steelhead, where more fish were detected as strays spawning in other tributaries than returned to the Tucannon River itself. These high straying rates are a double-edged sword, further depleting imperiled populations like the Tucannon River as well as reducing the fitness of other populations as strays may lack the local adaptions necessary to produce viable offspring in the streams where they end up spawning.

A Rough Trip Downstream – Mortalities Associated with the Hydro System.

With fishery impacts and straying only accounting for a small portion of the overshoot fish that did not successfully return downriver, what happened to the rest of these adult steelhead? Well, the biggest source of mortality appears to be downstream passage through the hydro system itself.

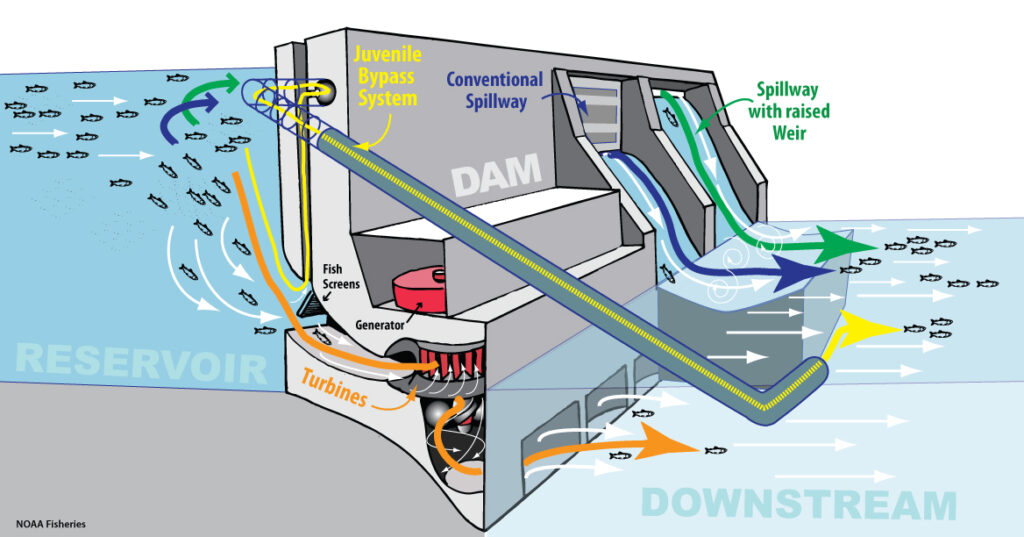

Fallback steelhead are surface oriented as they move downstream. When they encounter a dam, they prefer to utilize spillway routes to navigate past the barrier. Unfortunately, spillway routes are not typically available when the majority of fallback steelhead need them.

Image: NOAA Fisheries

At most dams on the Columbia and Snake Rivers, summer spill programs and juvenile bypasses are shut down in late summer. The exceptions in Columbia River are at Priest Rapids and Wanapum Dams, where surface spill routes remain open until November 15, covering part of the period when fallback steelhead are moving downstream. Similar extended spill periods were adopted in 2020 at McNary and the Snake River dams, from October 1 to November 15 and March 1 to March 15, but only occur 3 days a week and for just 4-hour windows on each of those days. When a surface route isn’t available, adult steelhead are forced to go through the dam’s turbines where they face higher mortality rates.

Downstream survival rates for adult steelhead through the hydro system are still poorly understood, but survival appears to decrease as fish length increases. A study at McNary Dam in 2000 showed surface routes have 97.7% survival while turbine routes only had 90.7%, but similar studies have not been conducted at other dams in the basin. Assuming that survival patterns are similar at the other mainstem dams, overshoot steelhead from the mid-Columbia River tributaries falling back downriver to their natal streams would be expected to experience a 32.3% and 38.6% cumulative mortality rate when passing through the turbines on the four Lower Snake River dams or the five dams on the Columbia River, respectively. Note that this would mean only 61% of mid-Columbia steelhead would be projected to make it back downstream below Priest Rapids Dam, aligning very closely with the 59% observed in the Murdoch et al. study.

The challenges facing adult steelhead that have overshot their natal tributaries also affect kelts (i.e. post-spawn steelhead) attempting to migrate downstream and back out the Pacific Ocean. Repeat spawners are an important life history component of steelhead. They have much higher lifetime reproductive success than single spawners, thereby helping to increase the resilience of the species as a whole. However, at less than 2%, steelhead populations in the upper Columbia and Snake Rivers have a have some of the lowest repeat spawning rates. Mortalities at dams not optimized to pass adult fish downstream is a key factor contributing to this.

Image: Murdoch et al 2022

Changes are Required to Improve Steelhead Survival

These recent studies highlight critical, previously underestimated impacts the Columbia Basin’s hydropower system has on adult steelhead, especially overshoot and fallback fish migrating high into the system seeking coldwater refuge. This issue is particularly pressing for mid-Columbia steelhead populations and is one of the major factors limiting their recovery. When steelhead from these rivers successfully make it back to freshwater, they experience overshoot rates of up to 50%, with up to 40% of those fish never returning downstream to spawn in their natal rivers.

As the climate continues to warm, and the basin’s slow-moving impoundments continue to exacerbate water temperature impacts, overshoot rates for summer steelhead are also likely to increase, putting further stress on already depressed populations. As such, managers must properly account for these fish in their population evaluations and need to consider urgent actions to reduce overshooting and improve fallback success rates and survival.

Image: Gary Marston

Providing alternatives to passing through the turbines during the fall and late winter when steelhead are falling back downstream would be an important first step. Increased flows would allow fish to use spillways. Richins and Skalski showed that increasing spill in March reduced mortality and improved fallback success for eight of the eleven hatchery and wild steelhead stocks in their study. Increased March spill would also help improve the survival of kelts passing downstream as well.

While management and infrastructure changes are needed to ensure higher rates of steelhead survival throughout the Columbia Basin, the particularly problematic rates of overshoot, straying, and fallback in the Snake River only add urgency and further evidence for the need to remove the four Lower Snake River Dams.

Learn more about Trout Unlimited’s work to restore a free-flowing lower Snake River and replace the services they provide at www.tu.org/lowersnake/