Today is bittersweet. This will be my final post as Science Director for Wild Steelheaders United.

Seven years ago, Rob Masonis reached out to me about a new job with Trout Unlimited. His goal was to launch “an ambitious and hopeful effort to protect and restore the wild steelhead.”

Rob’s idea came together as TU’s Wild Steelhead Initiative. What was innovative about his concept was its fusion of science and advocacy to drive improvements in management of wild steelhead populations and fisheries.

Wild steelhead have been my lodestone since I was a boy, fishing behind my family’s home on the Washougal River, Washington. I had been working on the Elwha Dam removal project for NOAA Fisheries, and while I loved research, I wanted to return to conservation because I was starting to feel as though a future with wild steelhead in it was slipping away.

My father had been, and remains, a life-long conservationist. He was, and is, my hero. He taught me how to cast, wade, read water, tie flies, and fish, and my youth was filled with more fishing adventures than any child could hope for.

Image: Shane Anderson/Swift Water Films

Above:John McMillan as a kid landing a wild summer steelhead in the Washougal River.

Image: Bill McMillan

He taught me that, despite their power and grace, wild steelhead are leaving this world more rapidly than they are coming into it, and that it is the responsibility of every angler to be a good steward of fish and rivers – even if that means making difficult adjustments in one’s fishing techniques and opportunities, and speaking out when management agencies or other anglers won’t do the right thing.

A few weeks later Rob came out to visit. I had met Rob before, several years prior, and I had long admired his communication and strength of argument.

We sat down and talked for a few hours. The discussion didn’t disappoint. So, after a week of talking things over with my wife, I accepted Rob’s offer to become the Science Director for Wild Steelheaders United.

At that time, I had not been on an airplane in well over a decade. I didn’t like to travel. I wasn’t very social. I preferred being alone on the riverbank or beneath the liquid line.

Within a month of being hired I had to fly down to New Mexico for TU’s annual meeting. I was immediately thrust into a large group of people and there wasn’t an ounce of solitude or a river in sight. But I was pleasantly surprised at all the wonderful, committed people I met there

While my preference for solitude hasn’t changed since I hired on with TU, I came to enjoy meetings with staff, board members, and others with the same commitment to conservation. And I’ve come to appreciate that a flight can take me not only to San Diego (the southernmost extent of the native range for wild steelhead), but also to the Dean River in British Columbia and its remote takeoff point in Bella Coola.

It’s unlikely I would have had those experiences without taking the first flight to New Mexico, and committing to more travel and interpersonal interactions than I had been accustomed to.

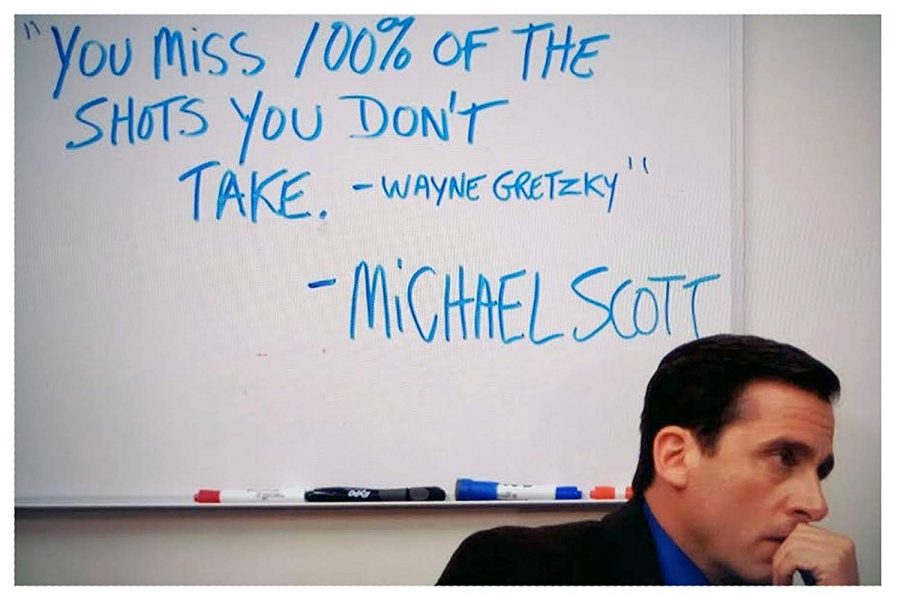

It’s important to get out of our comfort zone, at least from time to time. It provides opportunities for growth that are not otherwise possible.

Image: Shane Anderson/Swift Water Films

I will always remember my time with TU fondly. I have become very close friends with my colleagues at Wild Steelheaders United, which we often refer to as Steel-Team Six. And I’ve learned a tremendous amount from TU staff about strategy, communication, and actually getting s**t done.

We did a lot of good work during my time with Wild Steelheaders. I can’t leave without reminiscing a bit about what we have accomplished – and what issues remain unresolved.

***

The most pressing issue at the onset of the Initiative was the decline of wild winter steelhead on the Olympic Peninsula (OP), my home waters. At the time, fishing regulations allowed anglers to harvest one wild steelhead per year in eight different rivers. The use of bait and barbed hooks was also allowed.

This wasn’t a new concern. For well over a decade there had been a growing movement to eliminate retention of wild steelhead on the OP and to shift the fishery to catch and release only. However, previous angler-led efforts to bring fishing regulations more into compliance with the reality – steadily declining runs of wild fish, even in one of the last bastions of concentrated steelhead habitat on the West Coast – ultimately failed to deliver the necessary changes.

To that end, Wild Steelheaders United began a full court press and spent most of the next year meeting with the Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission and state fish biologists, analyzing data, educating anglers, and crafting a vision of what a sustainable fishery for OP steelhead would look like in this time of rapid climate change and intensifying angler pressure.

Lo and behold, our steelhead army won the day. That year, over 90% of the anglers that commented to the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) were in favor of eliminating harvest of wild steelhead and banning bait and barbed hooks on the OP.

Further, WDFW enacted a new rule, favored by over 70% of the anglers that commented, to ban fishing out of a floating device on an eight-mile section of the upper Hoh River. This rule allowed anglers to use a boat for transportation, but not to fish directly out of the boat. This is important because boat anglers have substantially higher encounter rates than bank anglers, and the Hoh steelhead population was and remains in long-term decline.

Image: Rob Masonis/Trout Unlimited

This rule, while a difficult adjustment for some, meant that anglers still could enjoy time on the water while also reducing their impacts on a struggling population of fish. This rule now has been employed more broadly by WDFW to keep anglers on the water in the Quillayute and Hoh Rivers the past two seasons.

To me, this is the future of our last, best wild steelhead rivers: a commitment to zero harvest of wild fish and adaptive angling regulations that reduce the overall impact of fishing on wild stocks.

I am proud that our group played a major role in getting this done on the OP. Why? Because anglers are more effective than ever before, while run sizes have declined and climate impacts have gotten worse.

If we want to maintain sustainable fisheries for wild steelhead in the Lower 48, we will have to give them the room they need to remain resilient. One way we can do that as anglers is to reduce our encounter rates with wild fish.

Scientifically, while we know that mortality rates for catch and release of wild steelhead are fairly low, we are not certain about sublethal effects – such as how catch and release affects the reproductive success of wild steelhead. Current evidence suggests catch and release can alter movements and migration of fish (Here), heighten levels of cortisol and other stress hormones (Here and Here), and increase fungal infections and reduce their reproductive output (Here and Here and Here).

At some point, research will more clearly quantify such impacts. Until then, if we want to maximize the return on our investments in habitat restoration and improvements, and ensure the next generation of anglers will have the opportunity to fish for wild steelhead, we will have to be more conservative in our approach.

***

Wild Steelheaders is committed both to conserving and restoring wild steelhead populations and habitat and to sustaining and improving steelhead angling opportunities. So it was natural for us to engage resource managers and the angling community on the Skagit River, where solid science made clear the spring steelhead fishery in this legendary river could be reopened. More broadly, we devoted ourselves to developing and implementing what we call the “Portfolio Approach” to managing hatchery and wild steelhead in Puget Sound rivers.

We weren’t the first group to try and reopen the Skagit – that charge was led by Occupy Skagit. Still, we worked hard behind the scenes to evaluate different potential fishery plans and to organize a cohesive advocacy position. Our collective efforts paid off, and in 2018, after almost a decade of closures, the Skagit spring fishery was reopened.

Image: Shane Anderson/Swift Water Films

Our work on the Skagit was not finished, however. The Skagit is one of the best remaining wild steelhead rivers in the Lower 48. Given the overall decline of wild steelhead, and the dwindling number of rivers that still have consistent wild runs, all waters such as the Skagit should be managed for wild steelhead exclusively, with no hatchery supplementation.

So we worked with WDFW and other conservation and fishing organizations to form the Puget Sound Steelhead Advisory Group (PSSAG). This group’s goal was to identify which rivers should be managed for wild steelhead, which should be managed for a combination of wild and hatchery steelhead, and to develop a diverse spectrum of sustainable angling opportunities.

PSSAG completed its work in 2020, resulting in the Quicksilver Portfolio approach to Puget Sound steelhead management. A key component of this approach is to maintain the Skagit River as a wild-only steelhead river at least through 2028. This will allow WDFW and tribal co-managers to monitor and assess the status and trends of wild steelhead in the Skagit River.

This approach also provides well-managed opportunities for angling in years when the population is adequately abundant and productive, and to collect good data over time to better monitor the sport fishery and evaluate whether more actions need to be taken to stem the decline of Skagit steelhead.

***

In addition to my Wild Steelheaders work on conservation and policy, I also spent a significant amount of time monitoring and conducting research related to the effects of two dams being removed on the Elwha River. For example, I worked with the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, Olympic National Park, the US Fish and Wildlife Service, and NOAA Fisheries/NWFSC to conduct redd counts for winter steelhead and to improve monitoring of summer steelhead returning to the Elwha River.

The resurgence of wild summer steelhead in the Elwha after the dams came out has been a truly heartwarming story of hope in a salmon-world that is otherwise filled mostly with bad news. We hired noted documentary filmmaker Shane Anderson to make a movie about their amazing story called Rising from the Ashes. If you haven’t seen this short film, give it a view – it will put a smile on your face.

The collaborative research effort on the Elwha resulted in publication of two manuscripts on native salmonids, including one on the spatial distribution and abundance of fish after dam removal and another on the genetics and origin of steelhead and rainbow trout. Both publications improve knowledge about the benefits of dam removal and highlight why and how dam removal could deliver similar dramatic benefits for salmon and steelhead in the Klamath and Snake Rivers.

I also collaborated with Matt Sloat (Wild Salmon Center) and Martin Liermann and George Pess (both of NOAA/NWFSC) to publish a study on the historic run timing and run size of wild winter steelhead in the Quillayute, Hoh, Queets, and Quinault Rivers. The work is important because it establishes a solid historic baseline for steelhead population abundance.

We encourage you to read the paper and our series of blog posts here, here, and here. In those, you will see that the run timing and run size have both declined substantially since the 1950s.

Image: Jonathan Stumpf/Trout Unlimited

These achievements, along with others, such as designating some rivers in Washington State as wild steelhead “gene banks,” including the Elwha, represent a step forward in managing and understanding wild steelhead and the fisheries they support.

None of this would have been possible without the dedication of TU volunteers, state council leaders, chapter members, and thousands of supportive steelhead advocates that follow the Wild Steelheaders website and social media for updates on steelhead science and policy issues.

But I am most proud, over my time with Wild Steelheaders, of the educational resources we helped build out and the outreach we did to connect anglers with these resources. When we started in 2014, anglers often had a difficult time finding, accessing, and interpreting the science on steelhead. One of our few staff dedicated to Wild Steelheaders, Nick Chambers, suggested we start a Science Friday blog series because well-informed anglers make better conservation advocates.

This series became surprisingly popular, and we used this forum over much of the past seven years to peel back the veil on wild steelhead biology, the impacts of hatchery fish, and other sometimes-obscure science related to steelhead conservation and fishery management. From sneakers and guards to Danny DeVito and Arnold Schwarzenegger, we tried to make steelhead science more accessible, relatable, and interesting for the layperson, and to break down technical findings in a way that anyone can understand.

***

Looking forward, there remain many challenges to recovering and sustaining wild steelhead across their native range. We’ve only scratched the surface in most watersheds.

With climate change making things increasingly hotter and drier in western North America, we do not have the luxury of time in our effort to make sure future generations will have some, if not all, of the opportunities ours has had to appreciate and encounter wild steelhead. It’s worth noting that salmon and steelhead have persisted through massive changes in the past, including volcanism, droughts, floods, and glaciation. And the remarkable life history diversity of steelhead makes them in some respects uniquely capable of persisting through periods of adverse conditions

But research suggests that wild steelhead will require all the diversity they can muster. That is why it is imperative to better manage hatcheries and fisheries today – these elements of the steelhead equation can reduce diversity in various ways, which in turn may limit the ability of wild steelhead to keep pace with climate change.

Though I’m moving on from Trout Unlimited, I’m not leaving steelhead science or wild steelhead conservation. I’m shifting my focus-area to the other side of the Pacific – I’m going to be conducting research on steelhead on the Kamchatka Peninsula with The Conservation Angler and scientists from the University of Moscow (Russia).

I need to recharge my batteries in a truly wild place, where the original diversity and evolutionary fabric of steelhead appear to remain largely unaltered.

At the same time, I’m not leaving the OP. I will continue to conduct science and implement a vision for sustainable fisheries in my home waters – the Quillayute, Hoh, Queets, and Quinault. Further, I will remain a part of the science team on the Elwha, where we will continue to track the recovery of wild steelhead.

Flying all the way to Russia wouldn’t have been a possibility in my mind if I hadn’t taken the job with TU and been required to travel around the West Coast.

In closing, I want to thank Trout Unlimited for getting me out of my comfort zone and helping me spread my wings. I want to thank all of you that helped us make progress in conserving wild steelhead. It’s clear that there is a large and growing army of wild steelhead advocates committed to taking a stand for the fish and their rivers.

When Rob Masonis reached out to me seven years ago, I was less optimistic than I am now about the future of wild steelhead. To me, that is the biggest reward – and accomplishment – of my work since then. In celebration of our wild O. mykiss family, I encourage you to keep putting the fish first, and wish you many happy days on steelhead waters.

~John McMillan

Image: The Office/NBC Universal