Untangling Steelhead and Rainbow Trout Dynamics in Washington’s Hood Canal: Part 1

Among the steelhead populations in Puget Sound, those utilizing the Hood Canal are some of the most imperiled, dipping to just 1.7% of their historic abundance by 2007, when they were listed under the federal Endangered Species Act.

Hood Canal is part of the Salish Sea on the east side of Washington’s Olympic Peninsula. Steelhead in this area have been in decline for a century. Today, fewer than 1,500 steelhead return to the canal annually.

With steelhead populations so low, resource agencies partnered with Long Live the Kings and other stakeholders to launch the Hood Canal Steelhead Supplementation Project. The primary purpose of this multi-year program was to evaluate whether a conservation hatchery could successfully improve abundance of wild steelhead (see here).

One of the major knowledge gaps associated with this project was how interactions between resident rainbow trout — especially those from above barrier waterfalls — might influence steelhead populations in the basins that feed into the Hood Canal. To help address this question, for three years (2013-2015) I led a research project in the Duckabush and Hamma Hamma Rivers (both tributaries to the Hood Canal) assessing interactions between anadromous and resident O. mykiss [link to paper].

This work had two main objectives: to determine the genetic interaction between above barrier populations and below barrier populations, and to evaluate the food web and growth dynamics of O. mykiss in the study area. We found some interesting results.

First, the two watersheds had different characteristics and very different productivity levels, with highly abundant O. mykiss above and below the barriers in the Duckabush River and high abundance below the barriers and low abundance above the barriers in Hamma Hamma River. Additionally, the Duckabush River has a second barrier that blocks anadromous salmon, but not steelhead.

These differences in the two systems resulted in some interesting genetic patterns. In the Duckabush 90% of fish below the barrier assign to (are genetically associated with) the above-barrier population, while only 41% of the below barrier fish assign to the above barrier population in the Hamma Hamma.

Interestingly, the O. mykiss collected at smolt traps primarily assigned to the below barrier population in both watersheds, suggesting a genetic component to anadromy and residency.

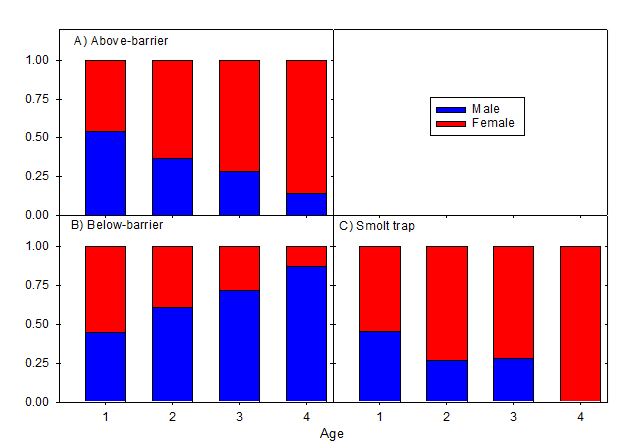

The smolt trapped fish were also predominantly female, and became increasingly female with age. In contrast the overall below barrier population was predominately male and became increasingly so with age. This makes sense, as the females have more to gain than males from going out to sea based on reproductive success.

Above the barriers the sex ratio was similar in younger fish but biased towards females in older fish. This was rather surprising and suggests two scenarios, likely working in concert. The first scenario is that males are more likely to emigrate from the above barrier population into the below barrier population. The second suggests that males remaining above the barriers spawn earlier and experience a higher post-spawning mortality rate than females.

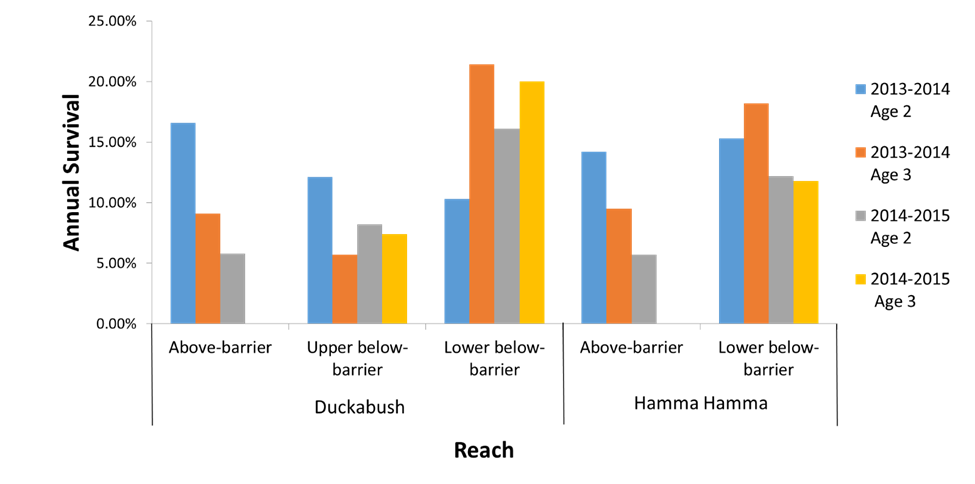

In addition, we wanted to determine survival rates for each of our study areas. To do this we conducted a multi-year “mark and recapture” study. The results of this research were particularly interesting, and a bit surprising.

First, the survival rate for O. mykiss was highest from age-1 to age-2 in all the above barrier reaches, then declined with age after that. Below the barriers where salmon are also present, age-1 to age-2 survival was typically similar or lower than above the barriers.

Additionally, age-2 to age-3 survival rates were typically higher than age-1 to age-2 survival rates below the barriers, despite out-migrating smolts, which the survival estimates would consider as mortalities. So, what was going on here?

The higher survival rates below the barrier certainly suggest something linked to the presence of salmon. In a few weeks, our next post will explore the nitty gritty details of this as we dive into the food web dynamics of these watersheds.

Gary Marston is the Steelhead Scientist for Wild Steelheaders United. Gary previously worked for the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, where his research focused mostly on the effects of hatchery production on steelhead populations.