Image: Gary Marston

Untangling Steelhead and Rainbow Trout Dynamics

In our last Science Friday post, we discussed the genetic and sex ratio patterns of above- and below-barrier populations of juvenile steelhead and resident Rainbow Trout in the Duckabush and Hamma Hamma Rivers in Washington, which described some odd patterns associated with the survival rates of these populations.

In particular, we saw low survival rates for older fish in the upper watersheds where salmon were not present, and higher survival rates for older fish in the lower watersheds.

This week we’ll cover how food web dynamics influence the differences in survival rates.

Image: Gary Marston

To assess the food web dynamics in these rivers I used water temperature, prey supply, diet data and modeling to determine the growth potential of O. mykiss populations. This approach was similar to that utilized by Jamie Thompson et al in Skagit River tributaries, covered on our blog here.

Like Thompson, in the Duckabush and Hamma Hamma we found juvenile O. mykiss grew best at water temperatures between 50-65°F, but that the growth rate varied depending on the feeding rate and quality of the prey items available. Optimum temperatures for growth typically only occurred from mid-summer through early fall, when prey supply was found to be a limiting factor in the upper watersheds.

Compounding the temperature and prey supply limitations, there was a much lower scope for growth for larger, older fish, requiring them to feed at a higher rate or seek out more energy-rich prey items to maintain growth.

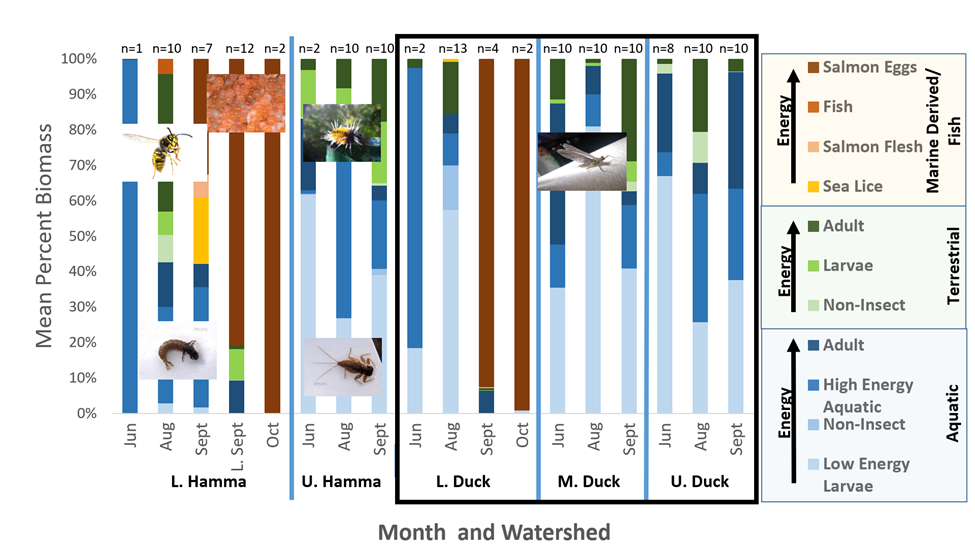

To get around prey supply limitations, O. mykiss sought out higher energy prey items such as terrestrial insects and caddisfly larvae (dark blue in Figure 1). In fact, caddisfly larvae were so prized by these fish that when holding them you could feel the gravel in their gut from caddis fly cases crunching.

Image: Gary Marston

However, selecting for higher energy prey was not enough to negate the poor growing conditions in the upper watersheds — we found there was very minimal growth potential for fish age-3 and older at the observed feeding rates and prey supply levels. This finding lined up well with the observed low survival rates for fish older than age two, and would be expected to incentivize any juvenile steelhead in the upper watersheds to out-migrate by age three.

One of the key takeaways from our analysis was the importance of robust salmon populations to the growth and survival of O. mykiss in the watersheds. While there were prey supply limitations in the upper watersheds during the summer months, the presence of salmon — especially summer Chum and Pink Salmon — provided significant food subsidies starting in late August.

The first food supply boost occurred as the salmon entered the watersheds and sea lice began falling off them. At the peak of the migration, sea lice comprised nearly 20% of the diet of juvenile O. mykiss. As the spawning began, the O. mykiss shifted almost completely to feeding on salmon eggs, which are almost three times as energy dense as aquatic invertebrates.

The influx of food provided by salmon arrived during a period of near optimum water temperatures for O. mykiss growth. This resulted in growth rates double those observed in the upper watersheds and provided a significant scope for growth for fish age-3 and older that was not present in the upper watershed.

The upshot of this was that the lower watersheds were able to produce larger healthier steelhead smolts, as well as support older and larger resident trout than the upper watersheds.

The insights into the food web dynamics in these rivers neatly explained the low survival rates observed for older fish in the upper watersheds and relatively high survival rates in the lower watersheds. The increased scope for growth can be expected to have carry-over effects promoting higher survival for steelhead smolts leaving the watersheds.

This work is yet more affirmation of the importance of the presence of salmon to healthy stream ecology in the Pacific Northwest, and the benefits of salmon for both steelhead and Rainbow Trout. It also suggests that wherever possible we should work on steelhead recovery and promoting robust salmon populations simultaneously.

Gary Marston is the Steelhead Scientist for Wild Steelheaders United. Gary previously worked for the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, where his research focused mostly on the effects of hatchery production on steelhead populations.