The communities and ecosystem of the Columbia River Basin need healthy and harvestable salmon and steelhead populations.

By Haley Ohms and Rob Masonis

Efforts to recover salmon in the Columbia River Basin have been ongoing for more than three decades, since Snake River sockeye salmon were first protected under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) in 1991.

But what does “recovery” actually mean?

For the communities that depend on salmon and steelhead (referred to collectively here as “salmon”), the answer to that question is of paramount importance. It determines the types and scale of conservation and restoration actions needed, the cost of those actions, and, ultimately, the extent of benefits that will be realized depending on what scale of “recovery” is achieved.

Yet, despite the enormous consequences flowing from how salmon recovery is defined and, in turn, accomplished, there has not been a shared understanding among the public, stakeholders and fishery managers. This lack of clarity and shared goals has stymied progress.

ABOVE: Lower Monumental Dam on the Snake River. Photo: Ben Herndon.

ESA Recovery Standard

Today, the majority of the salmon stocks currently living in the Columbia River Basin are protected by the ESA. This does not include the 117 populations, from 16 different stocks, that have been extirpated. Most of the listed populations have continued to struggle since they were listed, and recent runs have been less than 10 percent of what they were historically. In fact, fewer than two-thirds of the salmon populations in the Columbia River Basin are meeting the meager ESA delisting goals.

The ESA defines recovery as the point at which a protected species is no longer at risk of extinction. NOAA Fisheries, the federal agency responsible for implementing the ESA for salmon, generally defines ESA recovery as the abundance necessary to limit extinction risk to 5% over a 100-year timeframe.

It is worth pausing here to consider the ESA recovery standard. It is set at a level to minimize extinction risk, not achieve healthy and abundant salmon populations. Thus, it is not a standard sufficient for the federal government to honor its treaties with Native American tribes guaranteeing their right to harvest salmon. It is not a standard that would support consistent sport and commercial fishing opportunities, which provides critical revenue to rural communities and helps sustain anglers, guides, and fishing equipment manufacturers and retailers. It is not a standard that would support the river ecosystems relying on the rich marine nutrients delivered annually by salmon carcasses and eggs. In short, the ESA recovery standard is merely a backstop to avoid catastrophic loss (i.e., extinction).

Photo: Eric Crawford/TU.

The Columbia Basin Partnership Recovery Goals

The Columbia Basin Partnership defined what a successful salmon recovery could look like to meet community and ecosystem needs. In 2017, the Partnership was convened by NOAA Fisheries to determine what levels of salmon abundance would be required for each stock to meet the desires and needs of the diverse stakeholders throughout the basin. The Partnership included Columbia Basin Tribes; fishing, agriculture, conservation, river transportation, port, and hydropower interests; and the states of Idaho, Montana, Washington, and Oregon. Trout Unlimited was proud to participate in this important effort.

The Partnership established ambitious goals and defined recovery as “healthy and harvestable levels” of naturally produced fish (i.e., wild fish). It then set a range of goals for all 27 stocks of wild salmon and steelhead in the Columbia Basin. These goals were based on existing recovery plans, historical run-size estimates, traditional ecological knowledge, and desired ecological and societal benefits.

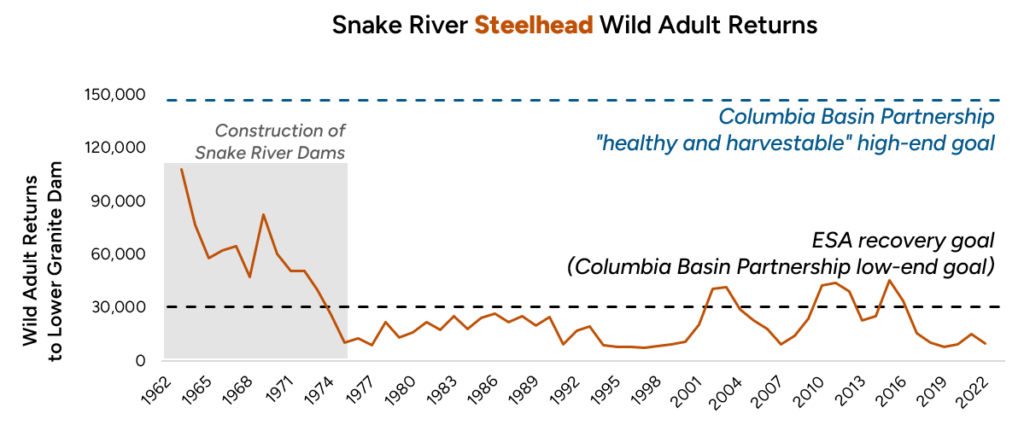

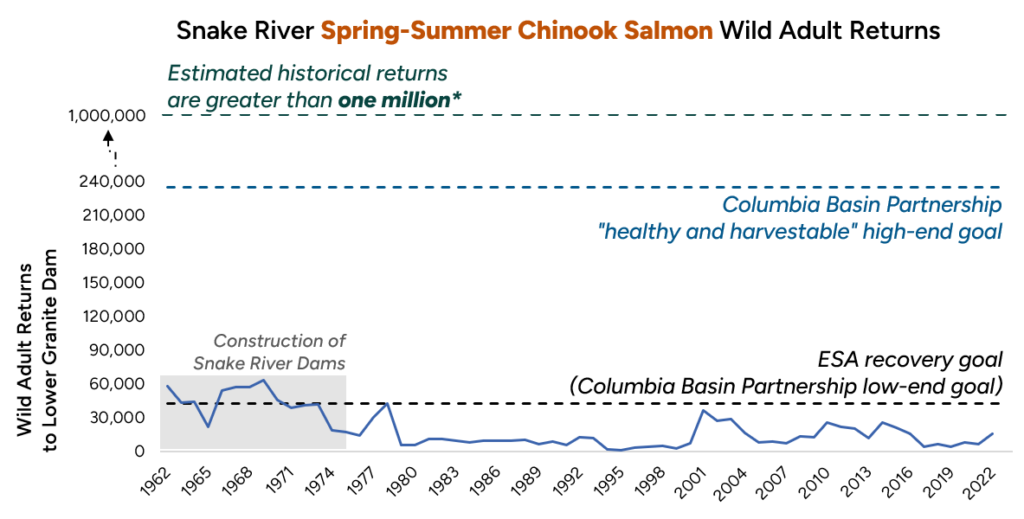

The Partnership’s low-end quantitative goals generally match the abundance required to delist a stock from the ESA. The high-end goals reflect “healthy and harvestable” population sizes that are generally 50 percent or less of historical averages.

The difference between delisting (i.e., ESA recovery standard) and “healthy and harvestable” (i.e., recovery that meets human and ecosystem needs) levels is vast for most stocks. For example, the Partnership’s “healthy and harvestable” recovery goal for wild Snake River spring/summer Chinook at Lower Granite Dam is 235,000 returning adults and the ESA recovery goal is a meager 43,000 – a difference of 192,000 fish. Similarly, the Partnership’s “healthy and harvestable” recovery goal for wild Snake River summer steelhead at lower Granite Dam is 147,300, while the ESA recovery goal is 30,800, a mere 21% of the “healthy and harvestable” recovery goal.

The Goals Selected to Guide Recovery are Critically Important

The goals used by managers and agencies to steer salmon recovery and permit various actions throughout the basin (such as the hydropower system) have profound implications. If the ESA delisting goals are used as the threshold for these actions, then wild salmon in the Columbia Basin may avoid extinction, but the litany of benefits that require restoring populations to “healthy and harvestable” levels will not be realized, including the right to harvest Northwest Tribes are guaranteed under federal treaties.

Crucially, there would be major differences in type and scale of the policies, restoration actions and investments needed to achieve ESA recovery versus “healthy and harvestable” recovery. For example, it might be possible to achieve the ESA recovery goals in a particular river basin without opening habitat blocked by culverts or dams because there is sufficient capacity within the accessible habitat to stave off extinction, but “healthy and harvestable” recovery couldn’t be met because access to the blocked habitat is needed for additional spawning and rearing capacity.

Photo: Matt Steinwurtzel.

The recovery goal chosen also has profound consequences regarding fishery management because harvest and hatchery practices consistent with meeting the ESA recovery goals might actually prevent salmon and steelhead populations from reaching “healthy and harvestable” levels. For example, using the lower ESA recovery goal might allow too many fish to be harvested in sport and commercial fisheries thus impeding the ability of populations to rebound. Or a certain number of wild spawners could be collected for hatchery broodstock without increasing extinction risk but removing that number of spawners could impede the wild stock from rebuilding to a “healthy and harvestable” level.

This disconnect between goals can have significant financial consequences as well. It will cost more to recover a salmon population that has lost its genetic diversity and adaptive potential due to excessive interbreeding with hatchery fish, or that has a severely depressed abundance due to sustained overfishing.

NOAA Report on Rebuilding Interior Columbia Basin Salmon

The difference between what is required to achieve ESA recovery compared to the Columbia Basin Partnership’s “healthy and harvestable” recovery goal for wild salmon was clearly spelled out by NOAA Fisheries in its September 2022 report Rebuilding Interior Columbia Basin Salmon and Steelhead.

Photo: Ben Herndon.

In the report, NOAA Fisheries explains its analysis of the science regarding the steps required to achieve the Partnership’s “healthy and harvestable” wild fish recovery goals and contrasts these findings with its past scientific analyses of the actions needed to achieve ESA recovery goals. Unsurprisingly, the report finds that a much more robust and diverse set of recovery actions are necessary to achieve “healthy and harvestable” wild salmon stocks in the interior Columbia Basin.

Below is a particularly telling excerpt from the Rebuilding Report:

“To make progress towards healthy and harvestable stocks it is essential that the comprehensive suite of management actions includes:

- Significant reductions in direct and indirect mortality from mainstem dams, including restoration of the lower Snake River through dam breaching.

- Management of predator and competitor numbers and feeding opportunities.

- Focused tributary and estuarine habitat and water quality restoration and protection.

- Passage and reintroduction into priority blocked areas, including the upper Columbia River (and, potentially, the Middle Snake River and Yakima River).

- Focused hatchery and harvest reform.

It will be essential that we implement all these actions, and that we do so at a large scale. While efforts in all these areas have been underway, there is a need in most cases to substantially enhance and focus implementation, and to incorporate new and emerging knowledge about effective implementation. These actions are needed to provide the highest likelihood of reversing near-term productivity declines and rebuilding towards healthy and harvestable runs in the face of climate change. (p.16)”

Redirecting Recovery Toward “Healthy and Harvestable” Salmon Populations

Participants in the Columbia Basin Partnership, representing diverse interests from across the vast basin, unanimously supported the goal of restoring wild salmon to “healthy and harvestable” levels. They determined – after several years of dialogue and analysis – that merely minimizing the risk of extinction, the ESA recovery standard, is not sufficient to meet the needs of the Columbia Basin’s communities nor ecosystem.

Putting that foundational work to use in its Rebuilding Report, NOAA Fisheries clearly stated what the science says is needed to achieve “healthy and harvestable” levels of wild salmon in the interior Columbia, and emphasized the urgency with which we must act. This is our roadmap to recovery.

Photo: Levi Old.

Because of habitat limitations, some Columbia Basin salmon stocks may not be able to fully reach “healthy and harvestable” levels, but communities in the basin don’t need to settle for today’s meager returns. For example, stocks in the Snake River have thousands of miles of high-quality habitat that is currently underutilized. These stocks are absolutely capable of meeting ambitious recovery goals if given the opportunity. Likewise, we should not aim for the lower recovery goals until we have determined, through a thorough analysis and good faith-effort, that recovering a particular stock to “healthy and harvestable” levels is not achievable.

The bottom line is this: if we are serious about achieving the Columbia Basin Partnership’s ambitious goal of “healthy and harvestable” levels of wild salmon, those responsible for managing salmon must use that goal to inform the selection of recovery actions, instead of continuing to limit themselves to the ESA’s extinction avoidance goal. Failure to do so will continue to frustrate salmon recovery efforts, fall short of the aspirations and needs of diverse stakeholders throughout the Columbia Basin, and do so at a high financial cost.