Guest author John McMillan is the Science Director for The Conservation Angler and has called the Olympic Peninsula home for three decades.

“The river will never recover!”

This is one of the responses I’ve seen in recent months from skeptics of the historic dam removal project currently underway on the Klamath River – the largest such project ever to date.

This claim is eerily like claims made prior to, during and after dam removal in Washington’s Elwha River – a river system in which I’ve studied steelhead and salmon for years.

On the Elwha, some even suggested the first Chinook salmon to make it above the former dams were just large rainbow trout that had been residing in the reservoirs behind them.

Skepticism is one of the cornerstones of science. But in the end, the story is about real-world science and outcomes. And the data from the Elwha – and from several other rivers where dams have been removed – are consistent in their story: restoring and improving connectivity benefits migratory fish species, mammals, birds and insects.

A connected river is good for nature, period. And because we are a part of and depend on nature, it is good for humanity too.

Since 2009, I’ve had a front row seat to what was, before the current Klamath restoration effort, salmon recovery’s grandest before-after experiment. Two old dams on the Elwha were deconstructed starting in 2011 with the lower of the two, Elwha Dam, followed by removal of the upper dam, Glines Canyon, in 2014.

Now, over a decade later, we’ve learned some lessons from the Elwha experiment. What did the sediment that had built up behind the dams do to the river and fish once it got moved downstream? Is the river healthy again? How are the fish stocks doing?

Below, I discuss these and other lessons from dam removal on the Elwha, using a series of images that capture the Elwha’s journey from the moment the first dam was breached to the sustained spatial expansion and natural production of salmon, steelhead and char.

Images: John McMillan

Bring on the heavy machinery.

Early deconstruction of Elwha Dam in 2011. I visited the site every few days to watch the progress.

Within a month the dam was breached. And with it, the plug was pulled on Lake Aldwell.

The reservoir drained over a few weeks and by early 2012, the dam was removed – the beginning of a new era for the Elwha River.

Image: John McMillan

With Elwha Dam gone, the freshly exposed lakebed more closely resembled a moonscape than a restoration project. Mud, silt, clay and sand that had been pampered and protected by the reservoir was now exposed for the first time in a century.

As Michael Scott said, “Well, well, well, how the turntables…..”

The river was back in charge. And it didn’t have a soft spot for Charmin-like sediment.

The mainstem river whipped across the former lakebed like a firehose, slicing through layers of muck like a hungry chap gobbling his first birthday cake.

Here, the Elwha’s gradient sharply increases as it exits the floodplain and approaches the old dam site proper, forcing the river to down-cut before dropping into a canyon headed by a series of falls and rapids.

The process was like a digestive system. The fine sediment on the floodplain provided the meal, the river then digested it in the rapids before spitting it out along the coastline.

The short-term result was, as you see next, a muddy mess.

Image: John McMillan

For three consecutive years (2010 – 2013) I measured turbidity almost daily in the mainstem Elwha River and several side channels and tributaries.

The tributaries were unaffected by dam removal, but the mainstem river and its side channels were all exposed to high levels of sediment for multiple years.

This photo shows the lower Elwha River in November 2012 at a flow of approximately 9,000 cubic feet per second (cfs) during the first notable fall storm following deconstruction of the Elwha Dam. The freed river was an aqueous concoction of trees, limbs, root wads and likely billions of small sticks, leaves and pine needles.

Turbidity peaked at 6,000 NTUs (Nephelometric Turbidity Unit) and ranged from 3,000 – 6,000 NTUs for two weeks.

For comparison, a flood of over 20,000 cfs in 2010 before dam removal produced a maximum turbidity of 600 NTUs.

During high water the rushing rapids smelled of mud. A scent so intense I swear I could literally taste it.

I presumed nearly all aquatic life was extinguished.

Image: John McMillan

Salmonids are resilient and can withstand short spikes in turbidity. They are not well suited to surviving extreme levels of turbidity for consecutive weeks, however, which is what occurred below both former dams from 2012-2014.

These juvenile hatchery Chinook salmon died due to a prolonged period of extreme turbidity in the spring of 2013. Most appeared to perish because they moved into the channel margins during high water. Presumably disoriented, they then became stranded as flows rapidly receded.

That day Ray Moses (Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe biologist) and I found thousands of dead juveniles. Hundreds were also still alive in isolated pools. Over the next few days, a variety of birds and mammals feasted on the dead and dying fish.

Fortunately, not all the smolts died, and other fish in between the former dams were able to access three clear water tributaries during dam removal. And large numbers of rainbow trout and bull trout existed above both dams and were unaffected by turbidity.

Nonetheless, the river below the dams took a huge shot. Estimates by NOAA and the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe suggested 90-95% of the fish and macroinvertebrates perished in the affected mainstem Elwha River during and after the dam removal process.

However, this wasn’t a surprise. Those of us working on the project expected big losses in the short term.

Image: John McMillan

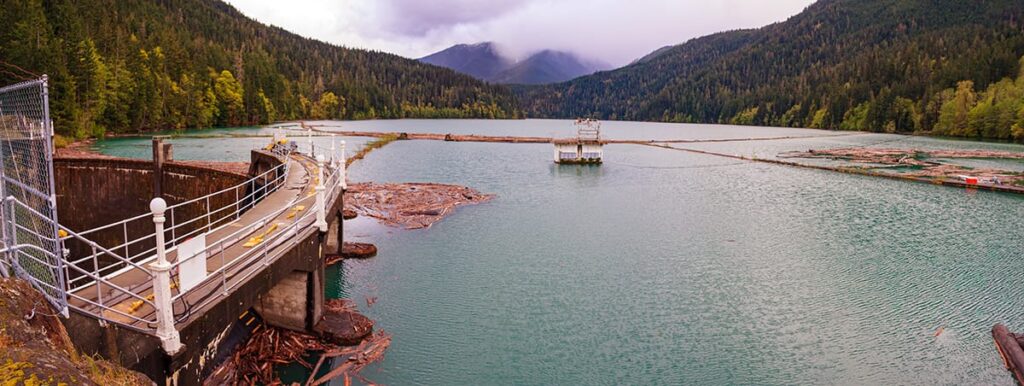

Lake Mills in 2010, formed by Glines Canyon Dam, was several miles upstream of Elwha Dam. The reservoir was enjoyed by anglers and boaters alike.

In 2014, a freed Elwha River meandered across the former lakebed and two years later, adult summer steelhead were observed above the dam by Heidi Connor with the National Park Service. It had been more than a century since an adult steelhead made its way that far upstream.

A decade later in 2020 the Elwha River’s new channel has stabilized, a riparian forest has developed, and the water runs cold and clean. A perfect gateway to the untouched wilderness that lies above, in Olympic National Park.

By 2022 the Elwha River below both dams reached normative levels of turbidity. The river had taken a substantial chunk of flesh out of the reservoir’s sediments, moving them down and out to the ocean, where it formed a new, large beach and spit – making fish and surfers equally happy.

Image: John McMillan

I snorkel the Elwha River several times a year, counting, observing and photographing fish and other aquatic life. It’s remarkable to how fast the fish have responded to the improved and reconnected habitats, such as these Chinook salmon preparing to spawn upstream of the former Elwha Dam.

While some fish stocks were and remain assisted by hatchery releases, scientists have now documented large numbers of naturally produced Chinook salmon, coho salmon, pink salmon, steelhead, bull trout and lamprey in the Elwha.

The increased production of coho salmon even allowed the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe a ceremonial fishery the fall of 2023.

Image: John McMillan

The Elwha River and its fish populations are still in transition. A century of deprivation of variable flows and sediment transport and other normal river functions is not easily or quickly overcome. It will likely take decades, or longer, for the river and its ecosystem to return fully to a more mature, steady state.

However, the early results on the Elwha are more than encouraging. Less than 11 years after both dams were removed, the river has basically been reborn. And the salmon and steelhead that once made this river one of the most famous fisheries on the Olympic Peninsula have begun to return with a vengeance.

Learn more about the ongoing Elwha River recovery: