On Monday, we launched the John Day Steelhead Project raising funds for a study being conducted by Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, Oregon State University, Oregon Watershed Enhancement Board, and a number of other partners. We’ve been impressed with the response to the crowdfunding campaign, with friends of Wild Steelheaders United coming together to fund $3400 towards our $10,000 goal in the campaign’s first 48 hours!

Today, we’re following up with more information from project partners on the potential impacts of temporary straying amongst John Day steelhead and why the work being funded through the John Day Steelhead Project will bring critical new science to managers of these fish.

The below post comes to us from Ian Tattam, Supervisory Fish Biologist at the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife as well as Logan Breshears, graduate student at Oregon State University who will be conducting the research being supported by the John Day Steelhead Project.

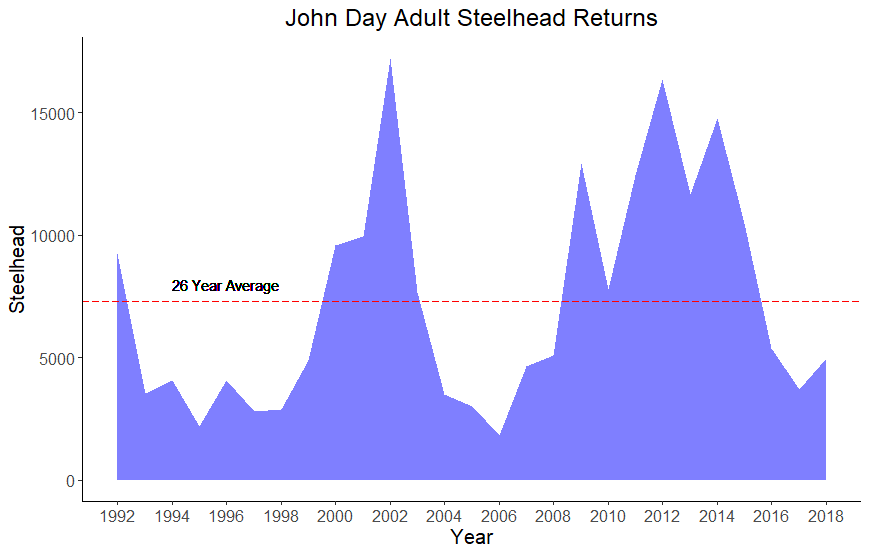

When it comes to Steelhead fishing, the John Day River has always been under the shadow of its neighbor to the west, the Deschutes River. However, in recent years, it has quickly become a destination fishery on its own merits. The John Day River is unique in that it is the second longest free-flowing river in the continental United States, and it is the longest undammed waterway in the Columbia River basin. The John Day River supports a native population of summer steelhead (Oncorhynchus mykiss), that is not supplemented by hatchery programs. Since 1992, the average number of adults returning to the John Day River in a given year has been hovering around 7,200 individuals. However, in peak return years, estimates reach upwards of 15,000 individuals (Fig 1.).

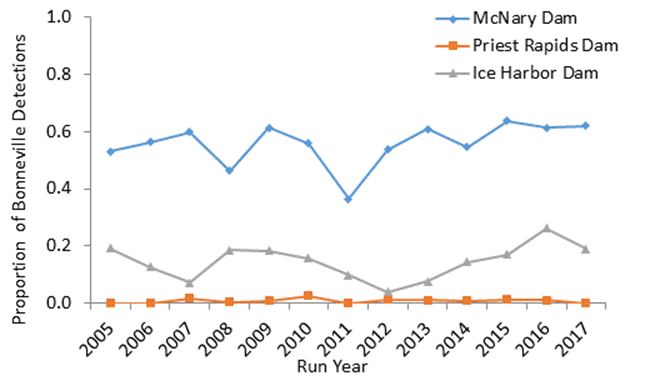

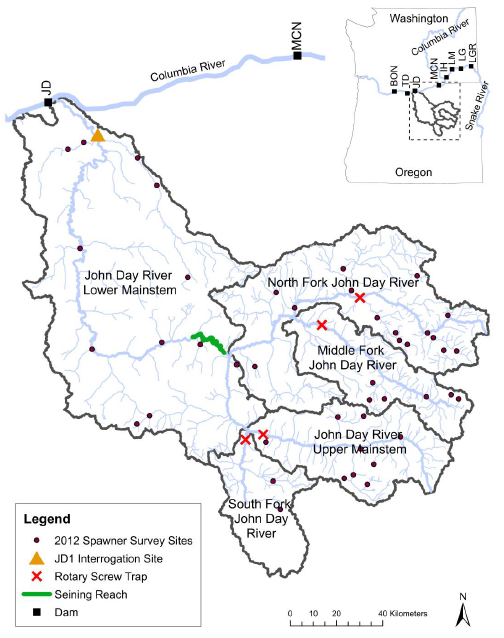

Beginning in 2005, PIT tag information gathered at dams along the Columbia indicated that a large proportion of John Day origin steelhead were being detected at dams upstream from the mouth of the John Day River. A PIT tag is a small radio transponder containing a specific code, which allows individual fish to be assigned a unique identification number. About 60% of John Day origin steelhead were being detected at McNary Dam (74 miles upstream). A smaller proportion of these fish were also being detected at Ice Harbor Dam on the Snake River (115 miles upstream), and at Priest Rapids Dam on the Columbia River (177 miles upstream) (Fig 2.). The distance between John Day Dam (JD) and McNary Dam (MCN) can be seen in Map 1. For the fish that “overshoot” the John Day River, in order to return, they must “fallback” over the dams. In the fallback process, fish are exposed to physical injury and increased energy expenditure resulting in some mortality. Entry into the John Day River is also delayed for fish that overshoot. With the overshoot typically occurring during September-October, some of these fish do not return to the John Day River until January-March. Remarkably, some of these fish successfully navigate their way back to the John Day River to spawn in their natal headwater streams.

The goal of our project is to track and identify specific migratory routes that Steelhead from the John Day River utilize to gain a better understanding of the “overshoot” and “fallback” phenomenon. We intend to track individuals by inserting acoustic tags and strategically placing an array of acoustic receivers between Bonneville and McNary Dam as well as near the mouths of tributaries and areas of cold water refuge. We plan to use acoustic tags with acoustic receivers equipped with temperature sensors to analyze their migration routes on a finer scale than what is supported by PIT tags. This will help expose areas that are critical for successful migration, or conversely, areas and times that are correlated with higher than expected mortality rates.

With the help of Trout Unlimited, we are seeking donations to purchase acoustic tags, and ultimately increase the number of steelhead we are able to tag. The acoustic tags we intend to use run at $350 per tag. People who wish to donate will be able to “adopt a fish,” and receive updates on the migration of an individual fish. This gives donors a unique opportunity to directly impact the state of the science, and they will be providing us with vital information to help improve the wild steelhead fishery in the John Day River. The baseline data gained from acoustic monitoring will provide an initial description of the problem, and inform possible avenues for future monitoring and/or management actions. Understanding migratory routes and their relationship to survival will identify possible factors affecting the overall spawning success of John Day steelhead. Reduced overshoot could equate to more steelhead entering the John Day River in early fall, benefitting anglers and reducing mortality incurred in the Columbia, benefitting steelhead. Thus creating a win-win for steelhead and anglers alike.

Figure 1. John Day adult steelhead returns from 1992-2018. The red dashed line indicates the 26 year average adult return; aproximately 7200 steelhead.

Figure 2. Proportions of PIT tagged John Day adult steelhead detected at Bonneville Dam, and detected again at McNary, Priest Rapids, and Ice Harbor Dams.

Map 1. Map of the John Day River basin. The five John Day River steelhead population boundaries are outlined, with streams accessible to spawning steelhead shown for each population. Black dots denote sampling sites visited during the 2012 spawning season for estimation of the percent of hatchery origin steelhead spawning in nature. Inset map of Oregon and Washington State shows the Columbia, Snake and John Day rivers.