Part one: New Olympic Peninsula report looks to our past for present-day answers

By Geoff Mueller

The difference between good and not-so-good steelheading is a story of highs and lows. When fish runs are up and in, connections happen. When they’re down and out — which across the Olympic Peninsula is the reality of recent times — it’s easy to imagine all the chrome we’ve missed as a result of arriving too late to the party.

If only we could thumb a ride back to the good ol’ days. But where and exactly when is the question. According to a new report, published in the North American Journal of Fisheries Management, on wild winter OP steelhead, co-authored by John McMillan of Trout Unlimited, Matthew Sloat of Wild Salmon Center, and Martin Liermann and George Pess both of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the answer is as clear as a glacial-green Queets River. The year: 1954.

Using historical tribal and sport catch data, the authors estimated an average run size of almost 20,000 fish in the Queets from 1948–1960. But in 1954, they estimated just over 50,000 wild steelhead flooded the Queets, which was the peak estimate for the study. While peak calculations don’t represent the average, to give that pinnacle number some context take a look at the Skeena system, where a healthy modern-day run is considered about 30,000 fish — spread across the river’s mainstem and its crown jewel tributaries such as the Copper, Bulkley, Morice, Kalum, Kispiox and Sustut. The Skeena drains a mammoth 21,000 square mile basin. The Queets’ basin, in comparison, measures 204 square miles.

Image: John McMillan/Trout Unlimited

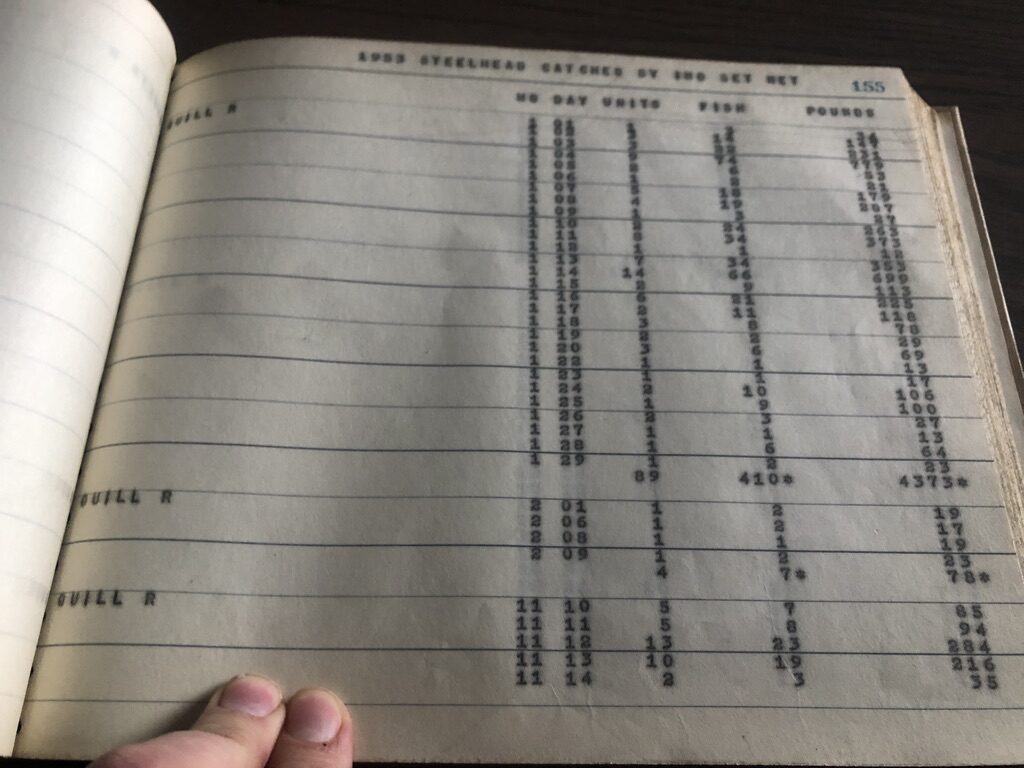

Above: A ledger the team discovered in an office in Olympia, Washington, contains detailed—and previously unknown—coastal steelhead counts from 1948 through 1960.

Image: Shane Anderson/Swift Water Films

Additionally, that same year commercial and sport fisheries harvested more than 5,000 wild Queets steelhead in the month of December, which is more fish than the river has returned in total in the most recent years. Nowadays finding a fat pre-Christmas steelhead, whether it’s from the Queets, Quinault, Hoh or Quillayute rivers, is as rare as bumping into Sasquatch at Pacific Pizza in Forks. The fact state managers closed Queets and Quinault sport fisheries last season due to rock-bottom fish forecasts exacerbate the low odds. This year the same goes, giving us even more reason to dream in reverse.

As you fire up the DeLorean and rewind the decades between now and the ’50s, the headlock loosens. Root causes of steelhead erosion, issues such as climate change, dams, hatchery programs, over-fishing, heated political stalemates, rampant human development, wholesale deforestation, unchecked pollution, et cetera, are undone one-by-one.

It’s in part thanks to historical catch records from before these impacts that long-held beliefs around steelhead abundance and run timing are being reexamined and challenged. The multi-year, joint-agency project from McMillan and his colleagues could be the catalyst for using what we now know about the past to strike a new path forward.

“I’ve been aware of historical catch data for OP steelhead for quite some time, and back in the early 2000s there were a couple reports, one by my dad [Bill McMillan] and Nick Gayeski and another by Peter Bahls, that used historical fishing data to evaluate potential changes in run timing and population size,” McMillan says. “Those reports were never peer-reviewed, however, and as the years passed I realized that many people were simply unaware that the populations had potentially changed, and so I discussed the concept of analyzing the data with a couple other scientists.”

Much of the data the new report hinges on spans the period circa 1948–1960, with additional earlier records unearthed, analyzed, and added to the contextual tapestry. Bringing those lost decades into view helps bridge the knowledge gap, better equipping state managers to restore threatened winter steelhead populations, while counteracting a shifting baseline syndrome — the dangerous idea that each generation of biologists and anglers comes to accept the status quo as the norm. Indeed, it appears this is what we’re seeing with wild winter steelhead in contemporary times.

“I think a longer-term data set provides a better perspective on these populations,” McMillan adds. “For instance, these stocks have long been considered healthy, at least until very recently. Our results suggest the populations are more depleted than initially thought,” he continues. “But we now have a better understanding of historical run size and timing, which provides benchmarks that can help alleviate the shifting baseline. That was one goal with the study.”

Image: SCoRE/WDFW.

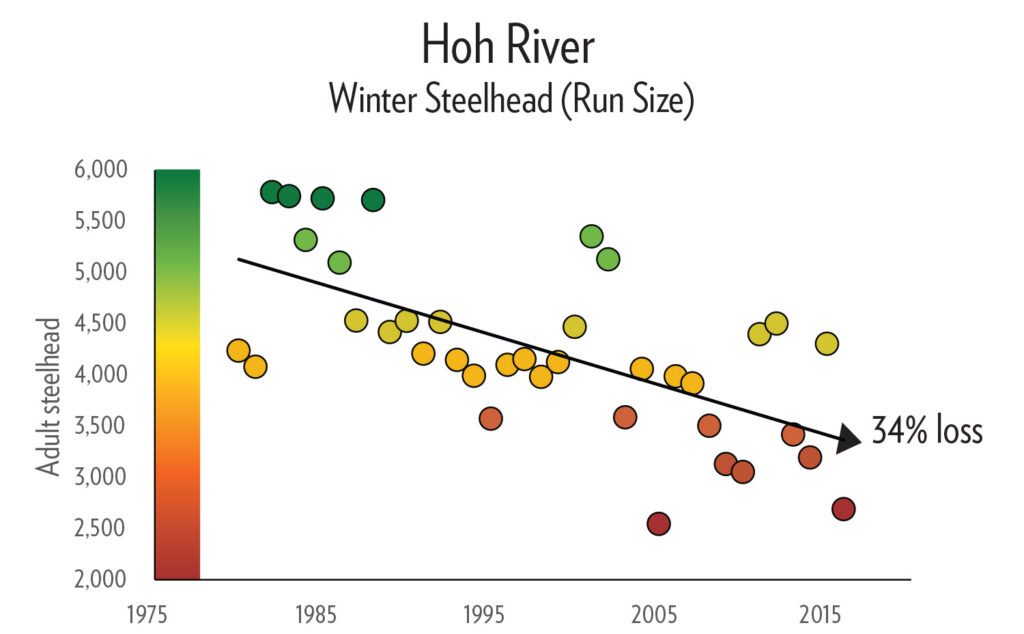

If perspective is the yardstick, the report measures up. At the core of “Historical records reveal changes to the migration timing and abundance of Winter Steelhead (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in Olympic Peninsula rivers”, we also learn that modern day wild winter steelhead migrations peak one to two months later than in previous decades.

“A big takeaway from our analysis is the large change in wild steelhead run timing,” Sloat says. “The loss of earlier migrating fish is stark and probably a big factor behind the declining abundance of these populations.”

Moreover, migration-timing breadth has compressed by about a month. The report estimates that contemporary wild winter steelhead abundance has cratered by 55 percent across populations compared to the 1948–1960 historical abundance records.

And perhaps the biggest takeaway: the report shows how even a modest extension of the period of record (thirty years in this case) increases our ability to identify population changes that today’s fisheries monitoring programs have completely missed.

“Although historic data implies the populations are in longer-term decline, results also suggest there are ways we can help the populations,” McMillan notes. “Rebuilding early returning life histories could increase diversity and help spread risk across a greater range of adults. Basically, improving diversity helps increase [the steelhead] portfolio of life histories, which in turn increases population stability and resilience.”

Image: John McMillan/Trout Unlimited

Greater diversity also means more steelhead in the river over a longer period of time. The report makes one wonder: How productive could the populations be if they were as diverse now as they were historically? It’s possible they could be much more productive, but testing that would require probing escapement goals, which in short is the number of steelhead determined needed — with a combination of policy and science — to maximize harvest while also maintaining the population over time.

In this way an escapement goal is also an estimation about the potential productivity of a watershed and population. Each population has an escapement goal, and the current target on the Queets is 4,200 fish. Last year’s escapement based on spawning surveys was 2,400. Remember, over 5,000 steelhead were harvested in just the month of December in 1954. Basic math tells you we’re unlikely to ever return really high numbers of steelhead — unless we rebuild the early-timed steelhead and test the capacity of the watershed.

Tomorrow, we continue with Steelhead Past to Present, part two in the series, unveiling this study from McMillan, et al, and the important research into past abundance and the shift in run-timing of Olympic Peninsula steelhead. On Friday, in part three, we’ll wrap up with a Science Friday post authored by McMillan, diving deeper into their research.

Partial funding of this research and study was made possible in thanks to the generosity of the Wild Steelhead Coalition. Visit wildsteelheadcoalition.org for more information on their work and efforts on behalf of wild steelhead.

Geoff Mueller is an editor, writer, creative director and steelheader. Reared in the fertile waters of British Columbia, he now splits his time between chilling with his fishy wife, Kat, in Fort Collins, Colorado, living part-time in a camper near a river in Dutch John, Utah, and migrating seasonally to Pacific Northwest nooks to get lost in the ferns — casting, stepping and fishing for answers.