By: Mark Taylor, Eastern Communications Director, Trout Unlimited

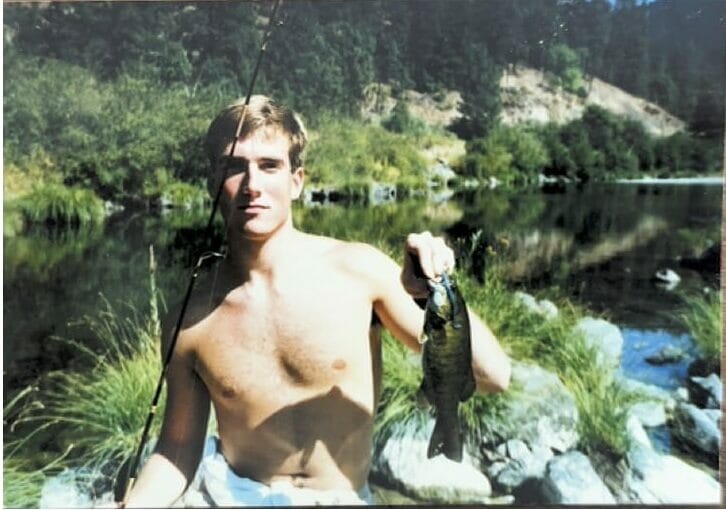

The thrill of the catch.

Gurgle, gurgle, gurgle…splash!

As I reared back and the fishing rod bent in a tight arc, I thought, “This is a good start!”

And it got better.

Seven casts. Seven fish. And 30 minutes of the best smallmouth bass fishing I’d ever experienced. Five of the seven bass were fat footballs in the 2- to 3-pound range and even the two small fish were solid 12-inchers.

Yet even as I laughed giddily every time another fish blasted my Whopper Plopper plug, I couldn’t help thinking that my “good” and “better” could be another person’s “bad” and “worse.”

Historically speaking

Smallmouth bass don’t belong in Oregon’s Umpqua River system. And while they’ve been in the watershed for about 50 years now, there are growing calls and momentum for trying to reduce their numbers in the Umpqua and other rivers to help protect Oregon’s struggling runs of steelhead and salmon.

And that movement has created a dilemma for some anglers who, while they may love fishing for steelhead and salmon, also love fishing for smallmouth bass.

I’m one of them.

I grew up on the lower reaches of South Umpqua and as a kid spent many summer days on the river with my neighborhood fishing buddy Jack. The river was warm in the summer. The winter steelhead run was long over. We caught mostly suckers, bullheads and pikeminnows. Then one day I saw a couple of different-looking fish.

“They looked kinda like sunfish but were greenish,” I told my dad when I got home.

A couple days later I found my dad filleting a couple of fish outside our garage.

“They’re smallmouth bass,” he said. “I’ve been hearing that they’re in the river now.”

The bass thrived, as did my passion for fishing for them. By the time I was in high school, smallmouth fishing was my number one obsession. By then, I’d fully bought into the catch-and-release ethic being espoused by prominent bass anglers — a bass is too valuable to catch just once!

The irony that anglers were whacking the South Umpqua’s wild steelhead but releasing non-native smallmouth didn’t dawn on me.

State of smallies today

I talked about smallmouth with my colleague Greg Fitz, a steelhead fanatic and advocate who lives in Washington, a few days before my most recent trip to visit family in Oregon.

Fitz, as we all call him, had given me a heads-up that Oregon fisheries officials were going to close the North Umpqua to fishing due to poor steelhead returns. (The agency says the run needs to be 1,200 fish to sustain the population; the run in 2023 was less than half of that.)

If I was going to fish during my visit, it was going to be for bass.

And Fitz, a Minnesota native who happily releases smallmouths when he catches them in their native range, was hoping every single one of the non-native smallmouths I caught would end up as fish tacos or crayfish food.

It’s a sentiment shared by plenty of other wild salmonid supporters and many (but not all) Oregon and Washington fisheries officials, who contend that while robust runs of steelhead and salmon might be able to endure some predation on smolts, the impact on poor runs is more profound.

As another colleague, Dean Finnerty, recently pointed out, the warming climate adds insult to injury, with associated rising water temperatures creating conditions that are less favorable to salmonids and more favorable to non-native species like walleyes, smallmouth, largemouth and striped bass.

Oregon no longer has size or bag limits on smallmouth bass in rivers. A veteran’s support group in Roseburg recently hosted a Smallmouth Bass Roundup, offering prizes for participants who brought in fish to be donated to a local food pantry.

On one Oregon river, the Coquille, fisheries officials have undertaken massive electrofishing efforts targeting smallmouths, and there’s even an open season for spearfishing bass. A press release suggested “fertilizer” and “crab bait” as sensible uses for smallmouth bass, a call that didn’t sit too well with some bass advocates.

Will encouraging anglers to kill every non-native predator fish (including walleyes in the Columbia and Snake River systems) actually make a big dent in the populations of those fish?

I suppose if we believe that releasing wild trout, steelhead and salmon can have a population-scale impact, then we must believe that killing predators can also have an impact on protecting steelhead and salmon smolts, as well as other native species, such as lamprey, a keystone species of coastal watersheds that is also taking a beating from bass.

On the other hand, think of the many instances where monumental efforts to eradicate non-native predators have failed.

If it’s nearly impossible to rid a lake of northern pike, even with poison, is there any realistic way to significantly reduce firmly entrenched populations of certain fish in massive river systems that are pretty much perfect habitat for them?

To Release or Kill

I took a picture of that first bass I caught on that recent evening. And then I released it, just like I released the others I caught that outing.

It was weird. In the past when I’d kept an occasional bass or two to eat, I’d felt guilty. Now I felt guilty for not keeping them.

As anglers, we are constantly learning and growing. Sometimes evolution requires changing deeply entrenched ethics and mindsets. That’s not simple.

On that most recent trip to my home waters, I wasn’t quite ready to flip the switch. Next time? I hope I am.