New Policy Looks to Guide Fisheries for Resident Rainbow Trout, Others

Last year, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife’s Commission (FWC) received a petition requesting WDFW adopt regulations to protect resident rainbow trout in watersheds with anadromy (wild steelhead), which included year-round catch and release and selective gear rules. Additionally, the petitioners called for the closure of angling in state-designated Wild Steelhead Gene Banks, and angling closures in watersheds where wild steelhead do not meet escapement goals.

In response to this petition—including a request that the petitioners withdraw the petition on the condition of policy action—the FWC directed WDFW staff to begin work on the development of a state-wide resident Native Trout Harvest Management Policy.

The Process

Based on the initial information provided by WDFW at a town hall meeting in February, the scope of the new policy will apply to resident native rainbow trout, cutthroat trout, and their subspecies including coastal cutthroat, westslope cutthroat, and redband and coastal rainbow trout.

The policy will not address native hatchery-origin trout, any non-native trout or char species, bull trout or Dolly Varden (native char), or anadromous life histories of any trout.

A draft of the new policy was shared with the public last month and the agency began taking public comment during a July 17 WDFW town hall meeting and will continue to do so through August 14.

We’re pleased to see WDFW taking action that could potentially lead to informed management for native trout fisheries, with hopefully an emphasis placed on establishing much needed protections for resident rainbow trout. It’s long overdue action, given that WDFW has a statewide management plan for managing adult steelhead, but they lack any management strategies and protections for the resident life history of steelhead.

The Importance of Resident Rainbow Trout

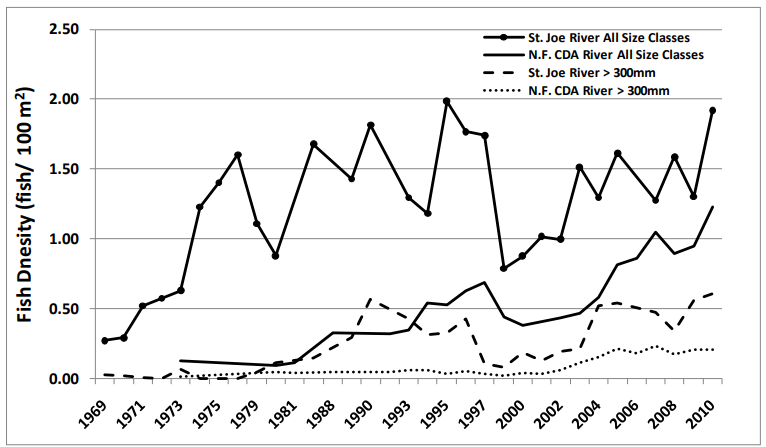

While steelhead and rainbow trout look different, and express different life histories (one heads off to grow in the North Pacific after spending one to four years in its natal stream while the other never leaves home) the diversity and reproductive health of native trout and steelhead are tightly linked and interdependent. Basically, healthy steelhead populations can require healthy trout populations with many steelhead runs depending on the productivity of their resident stream relatives.

Additionally, resident populations can also preserve the genetic diversity of their anadromous counterparts, even over multiple generations, as evidenced on the Elwha River, with the unexpected return of summer steelhead and with winter steelhead on the White Salmon River.

This genetic diversity also enables steelhead populations to maintain themselves during periods of exceptionally poor marine survival. For example, steelhead populations in the Hood Canal and Lake Washington have suffered steep declines in abundance due to poor marine survival associated with predation and other factors but we have seen a shift to more resident populations, which provide a lifeline for these steelhead options, once marine survival improves.

Due to the nature of their interconnectedness, it’s essential that recreational fisheries targeting the freshwater life history of these populations are conservative and the managers have the necessary data to support these decisions and regulations.

Recommendations to the Draft Policy

While we’re pleased to see WDFW take action on developing this long overdue policy, it’s our view that this first draft will require significant changes before providing new guidance for successful management of native trout.

The draft policy recommendations are separated into two geographic areas (anadromous zone and no anadromous zone) and each with two conservation categories (known conservation concerns and no known conservation concerns).

We do support the two geographic zones recommended but have concerns with the conservations categories.

First, as written, the ‘No Known Conservation Concern’ category is problematic. The status of most resident native trout populations in Washington State is unknown and consistent monitoring and evaluation targeted at the abundance and other viability criteria for these populations is rarely if ever conducted. The ‘No Known Conservation Concern’ category, as written does not put the burden of proof on WDFW to demonstrate that the populations can sustain harvest without causing a conservation concern. Instead, this would fall to individual staff or outside groups to raise and address any potential issues.

This approach is backward, and we believe it is essential that WDFW does their due diligence to show that native and resident trout populations can sustain harvest without resulting in adverse impacts to population viability (abundance, productivity, life history diversity and spatial distribution) and that the impacts will not negatively impact anadromous populations.

As such we see it essential to change the draft policy from two categories to the following three conservation categories: Unknown Conservation Concern, Known Conservation Concern and No Conservation Concern.

For fish populations with Unknown Conservation Concern status or Known Conservation Concerns status, WDFW should default to catch and release only with selective gear regulations to minimize impacts from recreational fisheries on resident and anadromous fish populations through all life stages. This approach to fisheries can also address the lack of resources for monitoring that can and will probably occur, while still balancing opportunity. While catch and release is often viewed as a socially driven regulation, it has a significant biological basis by allowing fish to reach larger sizes, express migratory life histories, spawn multiple times, and thus achieve higher levels for fecundity and productivity.

Along with the need for improved conservation categories that better represent the status of populations and more conservation regulations, the policy needs to clearly define the social and biological components of the plan. This is essential to ensure that conservation and opportunity are balanced and consider the magnitude of the conservation benefits against the opportunity costs of specific fisheries actions.

Next Steps

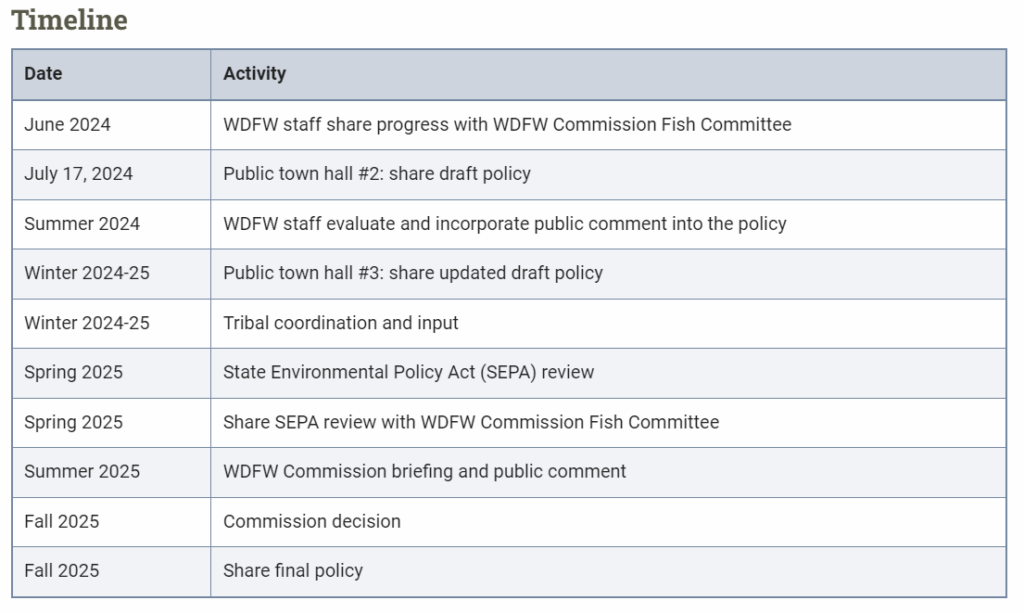

This current public comment period is the first of a few opportunities during the process to provide input, feedback, or suggestions to the draft policy. Right now, comments are being accepted through August 14 on the WDFW comment portal.

To assist with the series of three questions, we’ve provided this document to help guide the process.

Looking ahead, WDFW will be taking these public comments into consideration and incorporating them into the next draft of the policy, which will be presented at a third town hall later this winter. After coordination with co-managers, the State Environmental Policy Act (SEPA) review will kick off in spring of 2025, with final approval of the policy provided by the FWC in the fall of 2025.