A recent Seattle Times article highlighted issues impacting our state fish

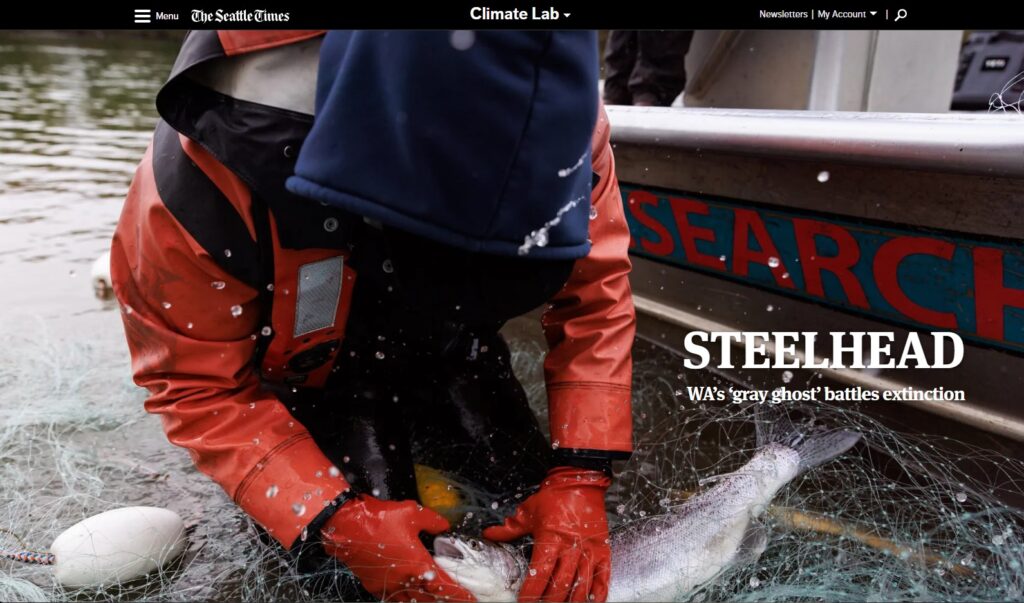

This fall in the Seattle Times, Lynda Mapes wrote a feature article called “Steelhead: WA’s ‘gray ghost’ battles extinction.” It was a front-page story accompanied by online videos featuring interviews with tribal fisherman, scientists, anglers, and the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW).

It is rare for wild steelhead to get this type of coverage in a major metropolitan newspaper. The story offered examples of how much these incredible fish mean to Washington anglers and tribes, and described the loss of habitat, impacts of poorly managed hatchery programs, and commercial and recreational fishing pressure that has combined to deeply diminished their populations.

John McMillan’s observations on the implications of climate change, and the resulting loss of summer stream flow in key spawning and rearing tributaries, were an especially stark warning. He’s been living on the Olympic Peninsula for over three decades and has observed these changes first-hand. They are part of the reason why his organization submitted a petition to the federal government to protect Olympic Peninsula steelhead under the Endangered Species Act (ESA).

Mapes provided a sobering overview for folks who might be unfamiliar with these iconic fish and a critical perspective on their status for anglers, conservationists, fishery managers, and elected officials to understand.

While we always appreciate Washington’s struggling steelhead populations receiving attention, the article did not provide insight into the actions required to recover wild steelhead runs to healthy and harvestable levels. Nor did it point to the river basins where we are seeing progress and learning important lessons that can, and should, be replicated more widely.

We aren’t giving up on Washington’s wild steelhead and believe there is a path forward for their recovery. In a letter to the editor we submitted in response to the article, we highlight some examples of these efforts underway. However, we thought it was important to take time to provide more context and describe our vision for the restoration and fishery management actions required to change directions for these incredible fish and the communities depending on them.

Legacy of Mismanagement

Across Washington State, and much of their native range, wild steelhead populations are suffering from habitat loss, dam building, impacts from poor hatchery practices, and overharvest. Against this backdrop and a warming climate, even as rivers close and angling opportunities dwindle, steelhead fishing has only grown in popularity. Anglers travel great distances to pursue steelhead and in many instances crowd onto the last rivers where fishing remains open.

Anglers, guides, and the local businesses that depend on visitors lurch from year to year waiting to learn if seasons will open or not. In the meantime, fish returns teeter at historic lows, frequently missing escapement goals in many popular watersheds.

Above: End of the day at a popular takeout during the winter steelhead season.

Images: Copi Vojta

The status quo approach to management is unsustainable and isn’t working for anglers and, in most places, it certainly isn’t recovering wild steelhead populations at the scale needed.

As Mapes points out, in recent years, where rivers haven’t completely closed to fishing, there have been modest regulation changes put in place by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) to limit angling impacts. This includes a harvest moratorium on wild steelhead by recreational anglers and a mix of limits on gear type, fishing from boats, and days allowed on the water.

Some of these changes were controversial and mainly driven by concerned anglers and advocates. While WDFW can be applauded for these efforts, broadly speaking, wild steelhead in Washington continue to struggle under a legacy of mismanagement. Rivers are fished until runs collapse, then they are closed, either by the managing state agency or the regulatory hammer of a federal ESA listing.

In 2008, a Statewide Steelhead Management Plan (SSMP) was developed to guide management across all limiting factors, with an emphasis on fisheries and hatchery practices, but it has yet to be even close to fully implemented 16 years later. This means that fisheries management and hatchery practices in many watersheds are still failing to comply with the State’s own guidelines and parameters.

Image: Copi Vojta

On the Washington coast, the escapement goals (the minimum number of fish that are needed to survive a fishery and spawn) guiding Maximum Sustained Yield (MSY) fisheries have remained stagnant for nearly forty years, though no one would dispute changes to ocean conditions, freshwater productivity, and habitat on the coast during that same time period. Out-of-date targets, combined with fisheries designed to fish down to, and sometimes below escapement, each year cannot recover runs in the long term, especially among the early-returning wild fish that are the most depleted segment of the population.

While there is considerable good work being led by many of the scientists and biologists at WDFW, it has often seemed that improved steelhead management (and recovery) is a low priority for Washington’s natural resource decision makers. Programs and plans regulating many fisheries are underfunded. Where fisheries are managed only under MSY, forecasts are regularly inaccurate. Other programs with limited scientific merit — like the small test fisheries used the past two years on the coast or angler utilization studies that are suddenly canceled with little explanation — are implemented instead of effective, systematic monitoring and creel programs.

About five years ago, steelhead management was added to the job duties of the Statewide Salmon Manager, but the additional responsibilities didn’t come with additional allocations of time or resources. As a result, statewide steelhead management duties have been neglected and secondary to salmon management, and approaches across the state are disjointed, inconsistent and often inadequate as a result.

When the Department misses deadlines or fails to fulfill mandates, the Fish and Wildlife Commission rarely has the time or resources to hold agency leadership accountable.

Image: Greg Fitz

To halt years of declines and rebuild durable wild steelhead populations, WDFW needs to prioritize and implement a far more ambitious, comprehensive management approach centered on recovery. When guided by science-based plans and supported with rigorous monitoring, sustainable fisheries can exist within these recovery efforts.

When WDFW fisheries management continues to fall short, anglers and advocates need to push them to do better. Otherwise, management oversight falls to the feds like what’s happening with the potential ESA listing on the Olympic Peninsula (And if an ESA process gets this far, the status reviews of past management efforts usually aren’t glowing). But when the plans are ambitious and rooted in best practices, then anglers and advocates also need to show up to tell the Fish and Wildlife Commission to support these efforts, and when necessary, make sure our legislature funds this important work.

21st Century Fisheries

We were glad to see the Skagit winter steelhead fishery mentioned in the Seattle Times article. We believe this fishery offers important lessons for anglers, tribes, and managers in other regions of the state.

After the river was closed due to low returns, and Puget Sound Steelhead were listed under the Endangered Species Act in 2007, the popular fishery was unable to re-open until returns improved and NOAA approved a new Skagit River-specific fisheries management plan prioritizing population recovery. The Skagit River Fisheries Management and Evaluation Plan was developed by WDFW and tribal co-managers.

It isn’t perfect, but it is a fishery that provides a model of how a wild-managed river can work to sustain a recovering wild fish population while also supporting a beloved sport fishery. Instead of relying on a doctrine of Maximum Sustained Yield (MSY), and minimal monitoring, like the steelhead fisheries on Washington’s coast, the Skagit and Sauk fishery now requires extensive creel surveys each day the season is open, and is managed under a more adaptive, tiered approach to steelhead angling and harvest impacts prioritizing recovery goals.

The fishery is a recommendation in WDFW’s Quicksilver Portfolio and will need to be continually updated and refined to achieve long-term recovery goals. In many ways, it offers an improved approach to how wild steelhead fisheries can be managed throughout their range to balance fishing opportunities with the need to rebuild populations.

The Quicksilver Portfolio is a management document of watershed-specific conservation, fishery, and hatchery strategies for Puget Sound steelhead and was developed in a WDFW advisory group over the course of three years, with final approval and adoption by the WDFW in 2020. Trout Unlimited was at the table throughout this process. The final product, Quicksilver, provides a diverse portfolio of steelhead rivers that achieve both conservation and fishery goals, and recommendations for an adaptive and experimental approach for the future of these fisheries with a goal for recovery. It provides opportunities for anglers to harvest hatchery fish in some rivers while identifying others as priorities for wild fish recovery and catch-and-release fisheries, with an emphasis on improving overall population monitoring.

This plan has been fully funded over the last two biennium budgets at the state legislature, with an additional budget request being put forth by the agency for the upcoming 2025 – 2027 legislative session. We continue to support funding for this work in the Washington legislature because we see it as a practical way forward to balance diverse fishery values and opportunities with improved monitoring and recovery efforts for an ESA listed stock.

Two years ago, we also participated in a similar (but less extensive) advisory group process where a diverse group of stakeholders helped WDFW develop a management plan for coastal steelhead fisheries on the Olympic Peninsula, Willapa Bay, and Chehalis Basin. The Coastal Steelhead Proviso Implementation Plan (CSPIP), created by the Coastal Steelhead Advisory Group, builds on the recommendations laid out in the SSMP while also updating fisheries management and monitoring recommendations to help guide sustainable steelhead fishing into the future.

Funding for implementation of the recommendations of the Coastal Steelhead Advisory Group was not formally requested by the Department in the 2023 – 2025 budget cycle. Last year, during the 2024 supplemental legislative session, the Department submitted a funding request that was missing many of the key components of the plan. This limited approach would have only further perpetuated status-quo management on the Coast and, on that basis, was not supported by TU. This request was rejected by the Legislature. The good news is that this year’s agency budget request to the state legislature includes a $4.8M ask to fully fund the initial recommendations in the CSPIP. We see it as a crucial step in the right direction and one that all anglers who fish for steelhead on the coast should support.

Image: Greg Fitz

For instance, the CSPIP includes elements of the 16-year-old SSMP that have not been implemented yet and directs managers to create Regional Management Plans (RMP) that contain, at a minimum, all information required in federal Fisheries and Evaluation Management Plans (FMEP) to increase the consistency of steelhead fisheries management, research, and conservation across the state. Developing RMPs for the coast, up to federal standards and alongside co-managers, will modernize harvest management tools to inform forecasting, maintain critical fisheries, and most importantly, achieve conservation goals.

Stay tuned for more ways to engage and support this important budget request.

Habitat Restoration

Alongside improved fisheries management, habitat restoration and reconnection is a foundational piece of the recovery puzzle. We need to ensure that our rivers are healthy and capable of supporting abundant and productive steelhead and salmon populations. Migration barriers like dams and culverts need to be removed so the fish can reach historic spawning and rearing habitat and sources of cold water, something that will only become more important with climate change. Our rivers need large woody debris and log jams, intact riparian habitat filled with native trees and vegetation, and connected floodplains so fish have rearing habitat in low and high flows, groundwater supplies, and hyporheic flows are replenished, and water temperatures are stabilized.

The Seattle Times article described habitat degradation on the Olympic Peninsula. Around the time the article was published, we’d just launched our new film celebrating the $30M of habitat restoration that Trout Unlimited and other partners are working on in these same watersheds. We’re biased, but we think the video is a great example of the collaboration and investments making this critically important work possible.

We’re proud of our colleagues doing this work across the state, but Trout Unlimited certainly isn’t the only group contributing to the effort. Tribes are leading ambitious projects to restore their home waters. State recovery groups and other nonprofit organizations are taking on great habitat restoration and reconnection projects. Federal infrastructure investments and state funds are supporting this work.

When this work prioritizes high-impact projects and is done strategically to use taxpayer resources efficiently, it should be applauded and expanded. It is a critical investment in the long-term viability of wild steelhead and salmon in Washington, and something that should unify all of us who care about these rivers, our native fish, and the communities that depend upon both.

The future is built on a comprehensive approach focused on recovery

For too long, Washington fishery managers have taken a piecemeal approach to the factors limiting and impacting wild steelhead populations. Too often, they’ve failed to fulfill their own guidelines when policy improvements were identified or mandated. As a result, steelhead numbers continue to decline and fisheries close.

The factors impacting wild steelhead—habitat degradation and disconnection, harvest and catch and release impacts, hatcheries, predation—are compounding and intertwined. Effective management must be as well.

A comprehensive approach that continues to restore degraded habitat and reform hatchery practices while updating fisheries management to fully account for the impacts limiting steelhead populations is required. When this work is guided by science, and prioritizes recovery, more wild steelhead reach the spawning gravel and more fish take advantage of available, and improving, habitat.

It won’t be easy, but it is what is needed to recover wild steelhead and maintain angling opportunities in the long run. As the Seattle Times article makes clear, steelhead populations are struggling and face many obstacles, including climate change. But we see practical ways forward and reasons to act on behalf of these incredible fish.

Image: Shane Anderson

Wild steelhead are resilient. On the Elwha River, numbers are rebuilding, and the fish are expressing dormant life histories after the dams came out. On the Skagit, new fishery models are demonstrating a better approach to management and the Quicksilver Portfolio shows the power of collaboration in Puget Sound.

In the Pacific Northwest’s network of Intensively Monitored Watersheds, habitat improvements are increasing the number of juvenile steelhead and salmon. Where managers pair this restoration with comprehensive fishery actions, it translates into improving runs of returning adult fish. (Likewise, where they fail to do so, we don’t see the return on investment from habitat restoration because not enough returning adults are allowed to take advantage of the improved habitat.)

Because of improvements to fishery management and habitat, a recent progress report on recovery actions in the Lower Columbia River found 11 of 22 steelhead populations have met or exceeded Endangered Species Act delisting goals, a sign of progress to inspire our work across the state.

Our job, as anglers and advocates, is to make sure 21st century fishery management and habitat restoration continue to be prioritized and funded and that this work is implemented comprehensively with an eye toward recovery above all else. At Trout Unlimited and Wild Steelheaders United, this is the focus of our advocacy.

We want to be on the water as much as any dedicated steelhead angler in Washington. Restoring durable wild steelhead populations is our priority and we believe it must also be prioritized by leadership at WDFW.

As we like to say, if we take care of the fish, then the fishing will take care of itself.