Last month, we shared with you the exciting and hopeful news about the return of wild summer steelhead to Washington’s Elwha River after two dams were removed in 2011 and 2013. For over a century these dams, located on the north Olympic Peninsula, blocked anadromous fish passage, decimated the salmon runs and nearly extirpated the summer and winter steelhead. But since these dams have come down, wild steelhead and salmon are rebounding, some species in numbers that were completely unexpected.

Photo by Shane Anderson.

In this era of dam removal, we’re experiencing renewal and recovery across steelhead country as migration barriers are torn down and rivers are restored. In California’s Carmel River, steelhead returned in unexpected numbers since the removal of the San Clemente Dam. Washington’s Condit Dam on the White Salmon River was torn down and now provides 33 miles of habitat to winter steelhead in the lower Columbia River basin. Work is underway to take out a diversion dam on the Middle Fork Nooksack River. Removal is set to begin on the four dams on Northern California’s Klamath River, which will open hundreds of miles of steelhead and salmon habitat. And discussion for the removal of the four Lower Snake River dams is on the table. The era of dam building has run its course. Whether built for power or flood prevention, many have irreversible impacts to the native fish populations and ecosystems.

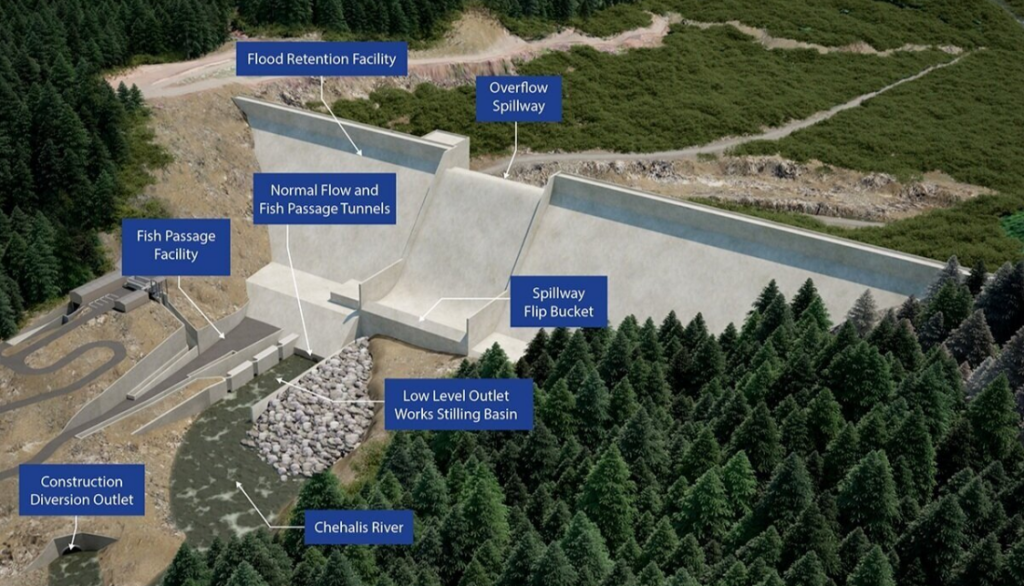

But presently, at a time when river enthusiasts and resource managers are recognizing the value and importance of free-flowing rivers for communities, fisheries, and economies, there are those that continue to propose that new dams be built in response to flooding problems. In southwest Washington’s Chehalis River basin, the local flood control district is proposing to construct a new flood retention facility and temporary reservoir near the town of Pe Ell in the upper watershed. This proposed dam would store water during major flood events and release the water over a period of about a month, with a stated goal to not stop floods, but merely reduce their impact in the many downstream communities, including Chehalis and Centralia along the flood-prone Interstate-5 corridor.

Photo by Shane Anderson.

With decades of commercial timber harvest in the Chehalis River headwaters, aggressive commercial development in the middle river along the I-5 corridor lead by unnecessary channelization where the river has been artificially narrowed, the basin has had issues with major flood events dating back 50 years. That compounded with a changing climate and increased storms of frequency and size off the Pacific Ocean—which bring atmospheric rivers to the upper basin—this 1.7-million-acre watershed, the second-largest in Washington, has a degraded ecosystem with, at times, just too much water and nowhere for it go.

Photo by Shane Anderson.

A Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) is currently out for public review from Washington’s Department of Ecology and it finds significant adverse impacts to 17 environmental elements, including reduction of steelhead, spring and fall chinook salmon, and coho salmon populations. You can read a summary about this proposal here.

Photo by Shane Anderson.

The proposed dam—at 254-feet tall and 1,220-feet wide—and temporary reservoir would back up and submerge 863 acres and almost seven miles of the river corridor above the proposed dam site. Additionally, the footprint created by the temporary reservoir would almost certainly render the habitat unsuitable for spawning, while the dam—although outfitted with fish passage when the reservoir is empty and a trap and haul system when full—will still create a migration obstacle for fish that attempt to access spawning habitat further upstream.

The site of the proposed dam is located directly in an area of high spawning activity for wild steelhead, coho, spring and fall chinook. This area has been identified as an important nursery for juvenile salmon and steelhead. For example, 15% of the steelhead produced in the basin come from the upper Chehalis River, at or above the proposed dam site, and it represents only 4% of the total habitat. Additionally, both steelhead and coho in this upper river section are genetically distinct from coho and steelhead in lower river areas. This section already is critical for steelhead and salmon production and protection of life history diversity, and will become more important in the face of climate change, as fish, both adults and juveniles, seek coldwater refugia at higher elevations in the basin.

Photo by Lee Geist.

Digging deeper, construction of the dam will also result in substantial adverse impacts on salmonid abundance, productivity, spatial structure, and diversity. These are more commonly known as the VSP (Viable Salmonid Population) parameters, which are four key metrics used to evaluate a fish population’s viability in three important ways. First, they are reasonable predictors of extinction risk. Second, they reflect general processes that are important to all populations of all species. Third, the parameters are measurable. And unsurprisingly, the DEIS reports that the proposed dam would negatively impact all VSP parameters for both steelhead and salmon.

Photo by Shane Anderson.

Therefore, it is our view here at Wild Steelheaders United, this proposed dam is a short-sighted approach to flood control with too many potential adverse impacts to the Chehalis River wild steelhead, and does not provide a holistic approach to living with the river using a whole-basin solution that includes fish, tribes, farms, sportsmen, and local communities.

We’re committed to this path, as Trout Unlimited has been engaged in this basin and process for almost a decade, from the participation in the early technical work groups aiming to solidify the Chehalis Basin Strategy and work toward their stated goals of flood damage reduction and aquatic ecosystem restoration, to providing technical comments along the way in this current process, both in 2016 and 2018, and earlier this year for the Aquatic Species Restoration Plan. We are dedicated to finding a solution that provides resiliency for both the fish and communities, but this dam proposal is not it.

Photo by Jonathan Stumpf.

As one of the few basins in Washington with no steelhead or salmon listed under the Endangered Species Act, the dam proposal has too many severe anticipated negative impacts to these fish and could easily push declining runs in that direction.

Just this past winter, both tribal commercial fishing and sportfishing for winter steelhead were closed due to a low run forecast. With the winter steelhead only meeting escapement two years in the past decade, a new dam will exacerbate that decline, and would be likely to result in more frequent – and potentially even permanent – closures of a once-vibrant winter steelhead fishery, and the ultimate displacement of anglers and pressure to the already popular north Olympic Peninsula, the last stronghold for wild winter steelhead in the state.

Photo by Shane Anderson.

However, taking no action for the flooding issues in the Chehalis River basin is unacceptable in our view. The flooding is getting worse, not going away, and will continue to be a problem for fish and people in the Chehalis River basin. This proposal provides a limited amount of protection for the people while creating potential irreversible damage to the steelhead and salmon. Let’s use—and continue—the amazing data collection that has happened during the past six years in the upper watershed for helping managers better understand the steelhead and salmon populations, work with local communities, including agriculture and businesses, and engage with The Chehalis Tribe and Quinault Indian Nation, to find a path forward that reduces local flood impacts throughout the basin and supports long-term resiliency of both fisheries and people.

To learn more about the issues facing the Chehalis River Basin, check out the new full-length movie, Chehalis: A Watershed Moment, from our friend and colleague Shane Anderson of North Fork Studios.

Read the comments submitted by Trout Unlimited/Washington Council of Trout Unlimited on the DEIS here.

To comment on this DEIS with Washington’s Department of Ecology, click here. The comment period is open through Wednesday, May 27, 2020.